by Garrett Oppenheim (1911-1995)*

“When I started doing regressions with my own patients, I read all the literature I could find on the subject. By now I’ve read a considerable body of it. I’m impressed by the quantity of evidence that these books contain, particularly the evidence so painstakingly accumulated by Dr. Ian Stevenson.

“When I started doing regressions with my own patients, I read all the literature I could find on the subject. By now I’ve read a considerable body of it. I’m impressed by the quantity of evidence that these books contain, particularly the evidence so painstakingly accumulated by Dr. Ian Stevenson.

I am also impressed by the enormous difficulty of seeing through our biases when it comes to interpreting all this evidence. In reading a wide range of views on reincarnation, one can’t help but realize how individual belief systems can color interpretations and influence the way we gather evidence.

Then where do I stand? While I know that we don’t have a final answer to the question of reincarnation—and that the final answers might make all our present beliefs look simplistic and childish—I do firmly believe that I’ve been around for a long time before slipping into this particular body, and that I’m going to be around for a long time after I slip out of it again.

Biased? I most certainly am!”

My skeptical interest in past-life therapy (PLT) was sparked in 1979 by a good friend who was a founding member of the Association for Past-Life Research and Therapy. One night at a symposium we were both attending, Zelda Suplee suggested that I let her take me into a hypnotic regression. In a very short while I found myself floating over a swampy scene and wondering, “What the hell am I doing up in the air like this?” “Am I dead,” I asked myself, “or am I just faking this to please Zelda?”

I seemed to be floating toward dry land. Close to the shoreline I saw a long, primitive, tunnel-shaped structure that was open on the end facing me. By now it was getting dark, and I noticed that a yellow light was visible through the opening. My smart-ass brain jogged me, “If that’s from an electric light bulb,” it said, “you’ve struck an anachronism and this whole thing is a fraud.” I decided to go down and investigate.

Pretty soon I was floating inside the tunnel, which, much to my brain’s chagrin, was lit by little flames coming from candles or tapers or oil lamps—I’m not sure, because what really interested me was what I saw below. A beautiful young woman, apparently dead, was laid out on a cloth-draped table in all the regalia of a princess.

“Who is she?” I wondered. And the answer surged up from inside myself: “That’s me!”

I came down closer. There was nobody else in sight, and the open ends of the structure revealed only darkness. The body must have been left here while the mourners went home for the night. And now a new thought came to me: what would happen if I got back into that beautiful body of mine and sat up?

With very little effort I arranged myself inside the princess, swung her legs—or my legs—over the edge of the table and sat upright. Almost immediately I got a strong feeling that I was being watched and that what I was doing was definitely not permitted. I pulled my legs back, laid my body down again, and got out of it as fast as I could. I was quite relieved when Zelda suggested that I come back to 1979.

Though I only half-believed in my princess at the time, this royal lady has stayed with me vividly for several years now. Her image has worked on me to the point where I am eager to find out who she was and why she died so young and what she means to me in my life today.

Some time after this experience I decided to use the affect bridge with a patient who was feeling defeated and depressed. After I had him relive a recent scene in which feelings were very strong, I wanted him to go back to the first time in his life that he ever had feelings like this. Only, when I asked him to do that, I left out the words “in your life.” And the next moment I was listening in astonishment to his description of a battlefield with legions of men in armor arrayed against each other. I soon learned that I was talking with a Carthaginian commander under Hannibal—a commander who had won many battles but was haunted by the depressing realization that the Romans were winning the war.

I am in no position to say whether this was an authentic regression or a metaphorical fantasy. But this one session was so helpful in relieving the patient’s depression and illuminating his problems that I decided to experiment further with PLT. I began cautiously using past-life regressions with selected patients. Today I am in the habit of asking most of my patients, in one way or another, “Who were you before you were you?” Let me, very briefly, tell you some of the ways I work.

My initial interview is fairly standard, except that it follows no strict format and I have no forms to fill out. I may ask a few questions to get the patient started, but then I use whatever subject matter he/she brings up to frame the next questions. Experience has taught me that this approach will nearly always lead me to the heart of the problem.

I always emphasize that I make no claim for the literal authenticity of past-life regressions in hypnosis, but I do question the patient tactfully on her/his beliefs. If I learn that I am working against a strict upbringing, I point out that there is considerable evidence in both the Old and New Testament of a widespread belief in reincarnation—and still more evidence that most of the references to it were deleted in the days of the Emperor Justinian. Finally, I assure the patients that belief in reincarnation is not required by this kind of therapy. I then suggest that they concentrate on the problem we’ve been talking about while I begin the induction.

My induction strategies are a mixture, drawn from Milton Erickson, Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Edith Fiore, Helen Wambach, Marcia Moore, and Denys Kelsey, among others, as well as some of the traditionalists and my own imagination. Sometimes I just ad lib: taking the patient’s presenting problem as a starting point. Sometimes, using a Kelsey technique, I ask the patient to tell me the first word that pops into his head; then the two of us free-associate from there. For example, the patient may give me the word “small.” I ask him what “small” makes him think of, and he tells me this is the way he feels when he’s with other people. I may then ask him to think of a scene where he had this feeling. I use the feeling as a double affect bridge, taking him back to an earlier scene in this life and a still earlier one in a previous life.

Frequently I use an induction technique specifically designed to lead into a past-life regression. One of my favorites, for example, starts with a walk through the Magic Forest, with all its beautiful sights, sounds, and feelings. The patient magically shrinks in age and size, reliving scenes from the various periods of the present life on the way back—preferably happy scenes. When early childhood is reached, I call attention to the distant sound of carnival music and suggest that we follow that sound. Presently we emerge from the forest into an open place where a great carnival is in progress, complete with clowns, rides, wheels of fortune, cotton candy, sticky children and all the rest.

We go into the Hall of Mirrors, where the patients can see themselves reflected as tall and skinny, short and fat, comically distorted, undulating, middle-aged, real old, and finally, the way they looked in previous lives. When this last image is seen clearly, I ask them to walk through the mirror and exchange bodies with the reflection. From there we move back and forth in the past life.

We go into the Hall of Mirrors, where the patients can see themselves reflected as tall and skinny, short and fat, comically distorted, undulating, middle-aged, real old, and finally, the way they looked in previous lives. When this last image is seen clearly, I ask them to walk through the mirror and exchange bodies with the reflection. From there we move back and forth in the past life.

Another method I like starts with a walk through the same Magic Forest but without shrinking the patient’s body. On this walk we emerge from the trees into a clearing on which stands a huge ancient temple built of massive stones. The stones are so old that one can see the minerals in them, giving the structure a shimmering, dreamlike appearance. Inside, in a corridor that runs the entire circumference of the building, there’s a virtually endless series of doors, one after another, each one a different color. Patients are told that they will know by the color which door to go through to reach the past life that is relevant.

Still another induction is one I’ve borrowed from Bryan Jameison, who claims he doesn’t use hypnosis to lead his patients into their past lives. But this technique sounds like an effective variant on the standard progressive relaxation method. When I employ it with my own patients they promptly go into beautiful trances. Using the Jameison method, I ask the patient to imagine a light inside his left foot, with the switch on the top of the foot just over the arch. I suggest that the switch be turned off and then a finger signal be given. We do the same with switches at the left knee joint and the left hip joint and repeat the whole procedure with the right leg. The patient now takes two deep breaths, going more deeply relaxed each time he breathes out. We then move to the hand, elbow, and shoulder on each side, followed by two more deep breaths. Next we put out lights on top of the head, middle of the forehead (in the position of the third eye) and middle of the throat. Two more deep breaths and we go to the base of the spine and the base of the skull. Patients now make a tour of inspection inside themselves, putting out any lights that may still be on, until the whole interior is enveloped in a warm, velvety darkness. At this point I usually depart from the Jameison method and do a hand levitation a la Erickson and then float the patient through space and time, or through a tunnel, into the past.

Where the patient lands in a previous life is usually a matter of pure chance, unless specific directions are given. It may be an everyday scene—a little girl playing in the yard with her brother or a shepherd tending his flock. Or it may be a scene of violent death, accompanied by screams and expressions of terror—as from a plane crash or an attack by wolves in the forest. In such cases, I immediately move the patient back to an earlier and happier scene in that life and work from there.

Sometimes patients see themselves from the viewpoint of onlooker, and other times they are right inside the body of their former self. Frequently they start as an observer but then gradually merge into a participant, experiencing the scene firsthand. Often there is trouble trying to recall a name, their age, or what year it is. I’ve found that counting usually helps. I say; “When I reach the count of 3, your name will pop into your head.” Or I suggest that in a moment someone will call them by name and they can then repeat the name to me.

I often regress the patient from this first scene to early childhood and gradually move ahead to the moment of death. Lately, however, I’ve come to favor going to the death scene sooner. This tells me how old the patient was at death and avoids the awkwardness of progressing to years long after the end of that life.

At the death scene, I ask the patient to review the life in vignettes. I take the happiest moment, the tenderest moment, the worst moment, the biggest mistake, the highest achievement, and so on. If any scene, including the death scene, proves too painful, I advise that they get out of the body and watch the proceedings without feeling any emotion or pain.

After the death scene, where there is little interest in lingering, I suggest a movement up to a summit from where the life that has just been completed is stretched out to the left and the life that is being lived up to the moment of hypnosis stretched out to the right. As both lives are surveyed, I suggest that they will begin to see connecting lines leading from the scenes in one existence to scenes in the other. They may perceive the significance of some of these connections at this point, but if not, fine—the meaning will emerge later from the unconscious. Finally I suggest a brief period to assimilate the experiences just passed through, followed by an awakening that will find the body fully refreshed.

Like many of my colleagues, I find that PLT often works where other approaches fail. A convincing demonstration of this in my practice was the case of a young female clown who lived in a trailer, crisscrossing the country with a traveling circus. Penny was suffering from an intense phobia that sent her into screaming panic whenever she found herself alone in the dark. With her itinerant lifestyle, this was a pretty regular occurrence. The panics usually lasted from twenty minutes to about an hour, but sometimes they would go on for as long as two days. At no time, fortunately, did they interfere with her performance.

Penny was able to see me for only three sessions before moving on with the circus, so it was imperative that we get going fast. Knowing that phobias often do dissolve rapidly with hypnotic imagery, I applied all the techniques that had worked well for me with other patients—desensitization, NLP, dissociation. But although Penny was an excellent hypnotic subject, the first two sessions got us nowhere.

On her third and last visit, I asked Penny if she’d be game to try a past-life regression. She said that the idea of reincarnation ran counter to her religious convictions but at this point she was desperate enough to try anything that might bring relief.

With that, I took her through my Magic Forest to the carnival, where we walked around a while enjoying the sights and sounds, and then entered the Hall of Mirrors. She laughed with childlike delight as she moved from one mirror to another to see her distorted reflections until we came to the mirror that showed her in a previous existence. Here she became wildly agitated.

“I’m in the garbage can!” she screamed “They’re piling stuff on top of me—sticks, clothes, papers. It’s dark. I’m suffocating! They’re setting me on fire!”

I quickly regressed her to a happy scene in that same life. She found herself at age twelve helping her mother bake pies for the Confederate soldiers who were gathered at the house. Soon she was taking the pies out to the soldiers and passing them around while she drank in their compliments. There was a big proud smile on Penny’s face as she described the scene to me.

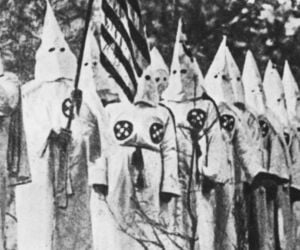

We moved forward in time, and once more Penny, now nineteen was in her home. In the next room a gang of Ku Klux Klansmen who had broken into the house were beating some black friends of Penny’s to death while Penny stood by, helplessly rooted to the floor with fear.

We moved forward in time, and once more Penny, now nineteen was in her home. In the next room a gang of Ku Klux Klansmen who had broken into the house were beating some black friends of Penny’s to death while Penny stood by, helplessly rooted to the floor with fear.

When they had finished this gruesome job, they moved in on Penny, surrounding her and beating her with sticks. Then they dragged her outside and stuffed her limp body into a garbage can, piling sticks and refuse on top of her until all was dark before her eyes. Her next sensations were the sharp pain of burning and at the same time suffocating with smoke. Then there was calm.

She moved now into a kind of twilight zone from where I guided her forward to her birth scene in her present life. Soon she was being held in her father’s arms. “He likes me,” she said. “It feels good.”

The first thing I did after rousing Penny was to pull out Webster’s Dictionary of Proper Names, because I rather doubted that the Ku Klux Klan had existed so early in our history. I discovered however that the Klan was “an obscurantist secret society formed after the American Civil War to maintain white supremacy in southern USA.” For whatever it’s worth, neither Penny nor I was conscious of ever having known this bit of history.

The first thing I did after rousing Penny was to pull out Webster’s Dictionary of Proper Names, because I rather doubted that the Ku Klux Klan had existed so early in our history. I discovered however that the Klan was “an obscurantist secret society formed after the American Civil War to maintain white supremacy in southern USA.” For whatever it’s worth, neither Penny nor I was conscious of ever having known this bit of history.

That third session took place more than a year ago at this writing. Penny, in a recent phone conversation told me she hasn’t suffered a single panic attack since then. The fear is gone.

In my PLT practice many persons come into this life carrying a burden of fear, like Penny, while many others carry a burden of anger. Chris was one of the angry ones.

This thirty-three year old probation officer had been suffering from intractable and incapacitating headaches for more than two years. The headaches seemed to be connected with his job, since they went away when he came home at night. By the process of elimination, he had pinned the blame on emanations from two television dishes positioned about a mile from where he worked. He coated the wall of his office on that side with lead, which brought some relief. But the symptoms rapidly developed to the point where telephone antennas, or even TV sets and radios, or any other kind of electronic equipment would swiftly induce pain on the top of the left portion of his head.

He had consulted several doctors, including a psychiatrist who tried biofeedback with him, but the headaches kept getting worse. A psychic friend of his got the impression that the problem traced to an immediate past life. As a youth, perhaps in New Mexico, the psychic said, Chris was exposed to uranium, which started a tumor on his brain, and excessive radiation may have been the cause of his death in that life. After thinking this over for nearly a year, Chris came to me for PLT.

Uncovering the story was no problem. We found his home and his school in New Mexico, as well as his mother, his teacher, and his playmates. At age 12, Michael, as he was then named, began to suffer from headaches that progressively worsened. His family doctor failed to find the cause, but a specialist finally went into Michael’s skull and discovered the tumor. It was inoperable.

The specialist told Michael’s mother there was virtually no hope unless she wanted to try radiation treatments, which were new and risky. Since the only alternative was certain death for her son, the distraught woman decided to take the risk.

Chris and I went through the hospital scene many times, each time adding vividness and detail to the picture. Michael lived through loneliness and hope lying on the metal table in the x-ray room by himself. As the treatment got under way, the pain in his head worsened, turning into an excruciating burning sensation. When it became unbearable, he floated out of his body and was able to look down at the charred mass on top of his head but was unable to call out or do anything to save himself. Frantically, he kept getting back into his body but was driven out each time by a more intense pain.

Chris and I went through the hospital scene many times, each time adding vividness and detail to the picture. Michael lived through loneliness and hope lying on the metal table in the x-ray room by himself. As the treatment got under way, the pain in his head worsened, turning into an excruciating burning sensation. When it became unbearable, he floated out of his body and was able to look down at the charred mass on top of his head but was unable to call out or do anything to save himself. Frantically, he kept getting back into his body but was driven out each time by a more intense pain.

Finally, he realized, with a burst of anger, that he was dead cut-off from a happy life at the age of fourteen. It was this anger, triggered by a few events in his current life that brought back the pain in his head.

We kept working on the anger, and each time he left the x-ray room Chris felt a little more forgiving toward the bungling technician. At the same time he began to get considerable relief from the headaches. He went into Crazy Eddie’s, a huge electronics store, and spent about ten minutes watching a program being duplicated on some hundred sets at the back of the store. Soon he was able to watch whole programs at home for varying periods of time, first in black and white and then in color. But he couldn’t get rid of the headaches completely.

Another psychic friend advised Chris to get at the cause of the tumor itself, suggesting that some kind of confrontation was necessary to resolve the problem for good. So, Chris came back for further hypnotherapy.

Our next regression took Michael back to age twelve, exploring for ore with a friend who was about a year older. The boys found some ore and took it to an assayer who told them it was uranium. Back in the area of the find, while they were having supper by a campfire, Michael noticed a strong metallic taste in his beans. Presently he realized that his so-called friend, wanting the ore entirely for himself, had put a little of it into Michael’s dish. Within an hour, Michael was feverish and delirious. Back home, his mother rushed him to the family doctor, who, as we know, missed his diagnosis. The rest of the story is familiar.

Chris figured that his murderer, if still alive, would be about 55 by now. At his request, I traveled him to the man’s living room, and we found the culprit sitting in an easy chair watching television. Nearby Chris saw an envelope addressed to this man in Lennox, Massachusetts. The street address was blurred, and Chris was now getting so shaky and apprehensive that I relaxed him and woke him up.

The man’s name, which is neither very common nor very unusual, is in the Lennox phone book, along with an address. Chris, at this writing, is planning to pay him a visit—regardless of the danger. At this suspenseful point, I must leave the story. I have no strong feeling one way or the other as to whether this man is the boy Chris knew in his previous life. I am hoping to dissuade him, if I can, from a direct confrontation. From a therapeutic viewpoint, I feel it’s not so important for Chris to confront this man as it is to forgive him, just as he forgave the x-ray technician.

One of the most enjoyable parts of my work is doing group regressions, in classrooms or club meetings or private homes. Among the big advantages, of course, is the well-known group contagion. Out of a roomful of, say, twenty-five people, three or four may sit there with their eyes wide open, looking at you accusingly, and you can’t give them the individual attention that might nudge them into trance. I’ve tried to resolve this problem by asking the entire group to keep their eyes closed and give themselves a better chance—and this has helped somewhat.

Our serendipitous benefit of group, I found, is that group members sometimes learn that they knew each other in a previous life. With this happy discovery, usually, comes the opportunity to develop their relationship from the point where it left off—perhaps a hundred or a thousand years ago.

Thus it came about that two very pleasant young women in one of my classes learned during a single group regression that they knew each other as members of the same American Indian tribe several generations ago. With that discovery, a casual acquaintance swiftly blossomed into a warm friendship with exciting plans to continue their parapsychological studies together.

For newcomers to hypnosis or past-life regressions, the group provides a comfortable setting in which to become familiar with these modalities. Even the apprehensive skeptic may find reassurance and safety in numbers. And many, when they learn that they like the experience, will go on to individual sessions.

One of the big handicaps of group hypnosis is that you can’t get feedback from each member as you go along. That can make it difficult to tailor your strategies to the needs of the members. This is one of the reasons I nearly always use hand levitation to signal how each member is responding to my induction. What they actually experience during the past-life regressions is something I have to wait until later to learn about.

I also feel handicapped at times by my inability to give some of the group members the intensive therapy that their troubles cry out for. I usually suggest to them privately that they see a therapist of their own choosing, but some of them seem to feel that the group should be enough.

Despite these drawbacks, group sessions often produce a quick, neat success that can have dramatic results in terms of symptom relief. I’m thinking of one young woman I’ll call Doris, who, during a group regression, went back to a life as a farm girl in the 17th century. One day, as she was feeding the pigs, she was set upon by four strangers who threw her into the pigsty, beat her mercilessly, and raped her repeatedly, while her younger sister watched in helpless horror. When they had all had their fill of sex with Doris, they pushed her into the muck and suffocated her to death.

I had taken the group to the summit to view the connections between their previous lives and their present problems. Now I asked Doris how this visit to the past might be of help to her today. Without a moment’s hesitation she blurted out, “I’m not going to be afraid of sex with my husband anymore!”

Her husband, she reported in class the next week, didn’t dig all this nonsense about reincarnation. I carefully reemphasized to her—and to the whole class—that it didn’t matter whether a reincarnation experience was literally true or not. What did matter were the therapeutic results. The following week, Doris announced that both she and her husband had to agree with me—“Wholeheartedly.”

The group setting often turns up some curious relationships. One night I was regressing a young housewife and mother at a club meeting where I’d been invited to conduct a weekly series. When I asked Jeannine where she was, she piped up in a frail childish voice, “I can’t see.” She had always been blind, she said, and had spent every day and every night of her life in the same dirty bed in the same smelly room. Her name was Mary, and she was four years old. She could make out moving shadows, or a door opening, or the vague shape of a woman standing nearby and staring. Not much more.

“Do they bring you food?” I asked.

“Sometimes.” Nobody ever touched her with any love or tenderness, Mary said. Her only toy—and her only friend—was a stuffed teddy bear, which she would hug and caress and whisper to. She said she simply couldn’t stand her mother, who would sometimes come in and just stay in the doorway, staring. “I wish she’d go away,” Mary said. Then turning her head toward me suspiciously, she demanded, “Why are you here?”

“I’m here because I want to help you,” I told her. To which she responded, “I’ll think about that.”

At seven Mary had learned to dress and sit in a chair by herself. She had one brother and one sister, but neither of them ever played with her.

At seventeen she reported with a weary sigh that she was very happy to be dying. After leaving her body and regaining her sight, she found she could look down on that frail shell which once held her identity. She described her body as crippled but pretty. Her mother, looking stern and thin, was with the body, along with some others. There was no father around, nor had there ever been within her memory.

The worst thing in her life, Mary said, had been the unending rejection. Worse than her blindness and feebleness was the total lack of touching and caring. “I couldn’t talk to them—they never understood. There was nothing I could have done differently.” Then with a sudden burst of feeling, she shouted, “I still hate them—every one of them!”

I moved Mary to the summit and asked her to take a good look at the unhappy life on her left and a good look at her present life on her right and see if she could find the connections.

There was a long pause. Then, “They’re still here,” she said. “Still here in this life.” Her brother in the past life is now her mother, she explained, and her mother in that blind childhood is now her son. “And I still hate them,” she added. “I still want to get even with them.” And what about the sister from the past? “I took care of her,” Jeannine said darkly, referring, as I learned later, to an abortion.

While she was still in hypnosis I tried to convince Jeannine that the past was over and done with and that perhaps it was time to forgive her mother and her son for their lack of understanding in another incarnation. “To go through life hating those close to you is to go through life hating yourself,” I suggested. “I know you’re right,” Jeannine answered, “but it’s hard to let go of my old feelings. In all my memory, all I’ve ever wanted was to be touched and hugged and caressed.”

Her husband, another member of the club, an athletic, youthful man named Don, regressed that same night to a dimly lit room where he found himself, oldish, balding and comfortable, in old clothes, studying a book on Eastern philosophy. It was written, he said, by those who love. “I’m alone here,” he told me. “This is where I stay.” When asked what year this was, he replied, “There is no time here. Time is an illusion.” What did he do besides reading? “I talk to the Father,” he said. “He hears me. He speaks to me.” And where is the Father? “He is everywhere. He is everything.” This hermit had no idea who his parents were and no interest in finding out. He had been brought up by a man who was now alive “only in spirit.” I inquired about his source of food. “It is provided. When I awaken from my rest, it is here. I know not who brings it.”

He spent all his days reading and communicating with the Father. Sometimes he would go to the top of the mountain on which he lived to take in the clean air, renew his energy, and feel at one with everything. I asked him his purpose in life. “The purpose is to serve all through the One.” The people who needed him, he elaborated, could reach out to him for help. “I direct His energy to them,” he added, “until they feel the One inside of them.” I asked him if he ever personally saw the people who reached out to him. “There is no need for that.” We moved forward to his last moments. He was very old and was on top of the mountain. “I will not go back. Here the spirit takes leave of the body.” He said that the best part of this life was service that strengthened the heart and made it glad. After death, he said, “Nobody anywhere—just a vast emptiness.” I asked him what kind of life he would like to live when he inhabited another body. “There must be people—close warm, touching,” he answered.

We shifted to the summit, from where he could view both lives and their connections. “I see myself with people,” he told me. “I give a different kind of help—a warm, touching kind. It helps them and it helps me. It’s wonderful.”

Across the room, Jeannine was crying quietly. As soon as Don came out of his trance she was in his arms. “Forgiving our son is going to be a lot easier now,” she said. “And my mother too—your mother-in-law.” Don patted her on the back. “It’s wonderful!” he repeated softly.

Whenever I get on the subject of PLT, people naturally want to know what my personal beliefs are. Well, for one thing, I don’t for a moment believe that all the regressions I get are authentic. In fact, it’s quite obvious that some of them aren’t. One patient, for example, described a life as a blacksmith who was forging armor for a powerful knight. The knight was scolding him for some trivial misfit in the greaves. When asked the name of the knight, he responded: “Sir Lancelot of the Table Round.” I knew then that I was in the land of myth. But sometimes the patient’s vivid picture of surroundings, dress, and people makes it difficult to doubt. Even more convincing are the emotions shown. I sometimes find myself so caught up in these emotional displays that I begin to feel like a participant myself. Originally I approached PLT with a good deal of skepticism. I dismissed my own regression as an interesting metaphor, much like a dream. But when it refused to leave my mind after several years, I began to take it more seriously.

When I started doing regressions with my own patients, I read all the literature I could find on the subject. By now I’ve read a considerable body of it. I’m impressed by the quantity of evidence that these books contain, particularly the evidence so painstakingly accumulated by Dr. Ian Stevenson.

I am also impressed by the enormous difficulty of seeing through our biases when it comes to interpreting all this evidence. In reading a wide range of views on reincarnation, one can’t help but realize how individual belief systems can color interpretations and influence the way we gather evidence.

Then where do I stand? While I know that we don’t have a final answer to the question of reincarnation—and that the final answers might make all our present beliefs look simplistic and childish—I do firmly believe that I’ve been around for a long time before slipping into this particular body, and that I’m going to be around for a long time after I slip out of it again.

Biased? I most certainly am!