Reviewed by Evelyn Fuqua, Ph.D. M.F.C.C. and Hypnotherapist

Reviewed by Evelyn Fuqua, Ph.D. M.F.C.C. and Hypnotherapist

In JRT Issue 8, Fall 1990

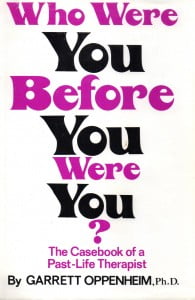

Dr. Oppenheim’s book is short (162 pages), is written in an informal style and is easy reading—all of which, hopefully, will make it appeal to the general public. Its humorous title, Who Were You Before You Were You?, should attract not only those who are seriously curious about past-life therapy, but perhaps even the total skeptics, who may pick it up initially simply because it promises to be entertaining. It will give them much food for thought.

The book covers all of the important basic concepts of PLT. It also gives many of the author’s personal insights as a result of his own PLT experiences. Oppenheim is never dogmatic in his comments although he clearly states his own belief system.

The author’s first professional experience with PLT was the result of his leaving out the words “in your life” when asking a client to go back to the first time he had feelings of depression and defeat. Oppenheim listened in astonishment as his client began describing a battlefield with legions of men in armor fighting against each other He soon learned that his client was a Carthaginian commander under Hannibal. This commander had won many battles but was haunted by the depressing realization that the Romans were winning the war and there was really nothing he could do about it.

That one session proved to be more effective than all his previous sessions together in relieving the client’s depression. As always, the author states that he did not know whether the experience was authentic or his client’s symbolic fantasy, but it was certainly a very helpful therapeutic tool.

Oppenheim discusses case histories of a number of his clients whose symptoms improved remarkably through PLT. But he also devotes one whole chapter to “one of my failures”—which therapists will appreciate, since we all have a certain number of these intractable cases. In one life this man was a wealthy Oriental merchant surrounded by women. He indulged heavily in numerous kinds of sexual activities. In another life he drank excessively. This was followed by yet another lifetime in which both drinking and sexual activities were indulged to extremes.

Finally, there was a drastic change when he became a revered priest of a church in Mexico. In this incarnation he was sorely tempted by fantasies of concubines, but he enjoyed his power as a priest too much to indulge these fantasies. Instead of viewing that life as the beginning of the upward path, however, he told Oppenheim, “I was trapped in respectability.”

He eventually terminated therapy, and later Oppenheim learned that he was still smoking, overeating, gambling, and drinking—a repeat pattern of his past lives. No amount of therapy of any kind seems likely to help this man.

The chapter titled “Why Do They Want to Change Their Sex?” is especially interesting, since little has previously been written about transsexuals. Evaluating and treating people who want to undergo a sex change is one of Dr. Oppenheim’s specialties. In addition to taking a thorough case history and asking many questions, he usually regresses sex-change candidates to early childhood, to infancy, and into the mother’s womb. He then suggests going back to a past lifetime. As an example, he discusses Steve, a 32-year-old, scholarly teacher who had been married to a charming woman for nearly 10 years when he came to Dr. Oppenheim. Steve went back to a series of past lives, in three of which he was a female who suffered violence at the hands of males.

Perhaps the most interesting parts of the book are about the author’s own past-life experiences. The chapter “A Karmic Case of Polio” describes his own insights through PLT. Oppenheim had polio when he was 14 months old. It affected both legs and his lower spine. At first he had to use two leg braces and a pair of crutches to get around. In describing his early life experiences he states that he never wanted to be identified as being in a group distinguished by limps and hobbles. He asked a friend, Tully, who is a hypnotherapist, to regress him to a life that was relevant to his polio.

He went back to ancient Greece, where he seemed to be a man of means, occupying an official position of importance. He had an attractive wife and a charming little girl, whom he loved dearly. When his daughter, Daphne, was about 7 years old, she became friendly with a boy who lived next door. The boy, Neleus, walked with a severe limp because one of his legs had been shrunk by disease. The father was not disturbed by the relationship until Daphne announced, at age 17, that Neleus had proposed to her and that she had accepted his proposal.

Her father’s reaction was one of shock and outrage. He told his daughter that under no circumstances was a child of his going to be married to a cripple! At her protests that Neleus was a wonderful man, he stated, “No cripple can be a wonderful man. They are all alike—cowardly, dependent, sponging on others, useless appendages on the body of society.”

That night Daphne stabbed herself to death. Her father spent the rest of that lifetime trying to convince himself that he was blameless in the tragedy, but the feelings of guilt and grief stayed with him until the end of his days. Oppenheim goes on to discuss the deep insights he gained as a result of that regression.

It was disappointing that there was not more follow-up on the case of Chris, who was poisoned in his most immediate past life by uranium ore. After guiding Chris back to that lifetime, in an effort to relieve his persistent headaches, Dr. Oppenheim took his client through hypnosis to the present-day living room of the man who had poisoned him in his past life. There was an envelope on the table addressed to the man. Although the address was blurred, Chris was able to make out “Lenox, Massachusetts,” on the envelope. The man’s name (which we assumed Chris also remembered) is in the Lennox telephone book. Chris planned to see him and then changed his mind. The headaches dissipated, which was the prime objective, but this would have been fascinating from a research point of view.

Dr. Oppenheim offers some interesting PLT techniques. In a number of cases he saw clients who came from faraway places to see him for several hours a day on several consecutive days. Although this would require a bit of advance scheduling, it would seem to be an effective approach.

Oppenheim uses guided imagery techniques in hypnosis, such as a walk through the Enchanted Forest, progressing finally to a carnival with a Hall of Mirrors where the client is asked to see herself as she was in a past life. He also uses the great Tree, the oldest living thing on earth. He asks the patient to communicate silently with the Tree, and then to touch the trunk of the Tree with her fingertips. She instantly finds herself leaving the ground, and presently coming down somewhere else on earth in an earlier time period. Readers who are therapists will find the details of these techniques useful.

The author’s use of the term “patients” rather than “clients” bothered me. I found myself repeatedly substituting the word “clients” when I read “patients”, since the author is a psychotherapist rather than a physician. But when I looked up both words in my dictionary. I discovered that “patient” actually seems to fit better than “client” if one is a doctor (not necessarily an M.D.). Thus, Oppenheim’s use of “patient” is correct, since he does have a doctorate. Therapists without doctoral degrees, it would seem, have no term to accurately describe those who seek their help.

In any event, the terminology is unimportant, since Dr. Oppenheim dedicates his book “to all those wonderful patients who gave their past lives that others might understand.” His sincerity and caring are strongly evident throughout the book.

Reviewed by Evelyn Fuqua, Ph.D.

M.F.C.C. and Hypnotherapist