by Paula Fenn

an EARTh Research Committee Report

an EARTh Research Committee Report

Abstract

This Research Report conveys a range of findings determined from a research study conducted with 15 regression therapists who were dominantly members of EARTh (80% EARTh, 20% non-EARTh). The topic of the study was, ‘What Does Not Work in Regression Therapy’ and the data was collected via questionnaires. The intention of this study was to generate data on this particular topic which would contribute to the field of knowledge within regression therapy also creating a reflective awareness about practice. The findings were analyzed using simplified versions of thematic and content analysis.

This methodological approach was adopted to structure the data into meaningful themes of problematic areas within which the study respondents had experienced difficulties either as practitioners of Regression Therapy and/or clients. The data communicated by the participants offered rich and meaningful content and allowed for a purposeful analysis which, indeed, allowed for reflection and a heightened awareness of practice, thus offering a contribution to the knowledge base of the field. While a number of the answers were unique in focus, there was an ability to collate the data into the

dominant themes of Resistance, The Integration of Other Therapeutic Approaches, The Making of Meaning, Not Attending to the Clients Practical Needs, Not Appropriately Attending to the Clients Material and Self Reflection/Self Awareness.

Introduction

The EARTh Research Committee recently conducted a research study on the topic “What Does Not Work in Regression Therapy”. The purpose of the study was to add to the body of knowledge within the field of regression therapy, as was previously communicated to our EARTh members, and was discussed in the Introductory Statement, which invited member participation in the study. It was determined that, rather than adding to the extensive knowledge and theoretical base on ‘what works’, it would be interesting to discover if there were any prevailing themes within our membership of practitioners on the difficulties that they have experienced in their own sessions as therapists and/or in their sessions as clients. This is a topic which embraces problems, difficulties and ineffectiveness. While we all aim for the Light in our work, we must also confront the shadows and integrate the more difficult aspects of our work into our experience as professionals. Jult as light and dark are opposing poles on the same continuum, success and failure connect to form a bridge of practical awareness. Indeed, most of the research participants, without prompting in the questions, worked positively with these somewhat opposing forces and offered examples as to how they had mitigated against and purposively worked with the presenting problems in their sessions in order to seek a successful resolution. Additionally, and alternatively, if they had come to accept that the session had proved to be ineffective in some way or another, they were able to create a meaningful understanding of what had not worked and why it had not worked. Some practitioners also noted surprisingly positive results for their clients after these “failed” sessions.

As a body of professionals, EARTh must always be in the flow of developing a knowledge base which informs practice. But what comes first, the knowledge or the practice? Is it not the case that our practice is informed by knowledge, but that as we practice we learn and develop a heightened and adaptive awareness of our methods? Knowledge and practice are thus interlinked. Continuing to bring a research based, practical understanding, to what we do as practitioners is complementary with and runs alongside the theoretical. Reflecting on practice, what we do and why we do it, is crucial in our evolution as practitioners and the evolution of the field of regression therapy.

Without flow, without processing and developing a greater understanding of our practice, we leave room for stagnation. This particular research study created an opportunity for practitioners to direct attention towards their own work and experiences and in so doing opened the flow of practitioner self-reflection, a key evolutionary aspect in terms of the use of Self in the work of regression therapy alongside the informed application of practical methods.

The primary audience for the research findings was determined to be our body of EARTh members. The purpose of this research study was to seek to understand “What Does Not Work” in some instances in regression therapy in order to inform practice, to add to the body of knowledge within the field and to communicate our ability as a body of practitioners to be reflexive in our approach to what we do. Perhaps certain themes emerge from the study of respondents’ answers, which could additionally and informatively contribute to these aims.

Research Methods

The research protocol embraced a dominantly qualitative approach which aimed to achieve open-ended responses to questions. The tool for collection of the responses was a short questionnaire. The questions were geared to generate textural descriptions of personal experiences, which is a hallmark of the qualitative approach to research. We attempted to generate data which assisted our learning about the research topic from those which were intimately involved, namely regression therapists. Quantitative data could also be gathered via the use of closed (yes/no) questions which would allow for a statistical analysis.

The qualitative data was analysed using a combination of content and thematic analysis whereby the researcher attempted to find recognisable and possibly linked content within the participant’s responses. Basic analysis at the quantitative level was also undertaken.

Requests for participation, information about the research study and questionnaires were sent to our body of 300 EARTh members via direct email from EARTh administrators, the EARTh Newsletter and the EARTh Facebook Page. Requests for participation were also verbally elicited at the EARTh Convention 2016 where hard copies of the questionnaires were distributed.

Study respondents completed the questionnaires, emailed them, and/or handed in handwritten answers to members of the Research Committee. The aim of the dominant online distribution technique was to reach a globally dispersed body of members and to elicit as many responses from our community of members as possible.

Confidentiality and an ethical lens is of importance in all research studies and was adopted within this research protocol. Some study respondents chose to remain anonymous while others declared their names. In terms of the analysis and interpretation of the data, all responses are rendered anonymous in terms of the descriptive answers shared in this report.

A literature review pertaining to the topic under review was not undertaken due to the Research Committees’ understanding that no previous research of this nature had been completed within the field. It may have been informative to collect data examples from textbooks and student manuals on the pitfalls and/or problematic areas to be aware of within the field of Regression Therapy. However, this was out—with the remit of this research protocol given that we were attempting to generate inductive (potentially

novel data/information) and not make deductive conclusions (comparisons with already known data/information). [Ed. note: comparison of these results with the first extensive survey of regression professionals would be insightful. Clark, R. L. (1995). Past life therapy: the state of the art. Austin, TX: Rising Star Press.]

List of Questions

Question 1: “As a practitioner of Regression Therapy have you ever had an experience where any part of the process appeared to be ineffective, did not work, and/or where you had particular difficulties with any part of the process?”

Question 2: “If you answered YES to Question 1, can you describe that experience or experiences and share any thoughts based upon your own interpretation as to why that part of the process appeared ineffective, did not work, or presented a particular difficulty?”

Question 3: “As a client of Regression Therapy have you ever had an experience where any part of the process appeared to be ineffective, did not work, and/or where you had particular difficulties with any part of the process?”

Question 4: “If you answered YES to Question 3, can you describe that experience or experiences and share any thoughts based upon your own interpretation as to why that part of the process appeared ineffective, did not work, or presented a particular difficulty?”

Question 5: “Are you a member of EARTh?” Please answer YES or NO.

Question 6: “If you answered NO to Question 5, could you please indicate any Regression Therapy Organisation you are affiliated with and if None please state this?”

Results

Quantitative Analysis – Fifteen people completed the questionnaire. From a body of 300 EARTh members this represents a sample of 5% of the potential responses. Due to the small sample size, we cannot create any grand theory from the results, which essentially means that we cannot make any broad generalisations from the answers provided. In order to be able to make any wide assumptions it would have been necessary to have a much higher response rate. However, we can bring forward some interesting findings in the qualitative analysis.

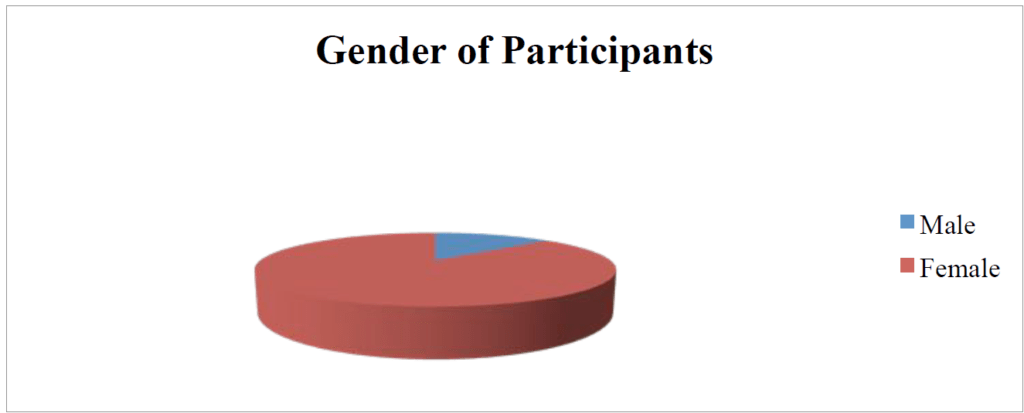

Of the 15 respondents, 12 were members of EARTh, 1 a member of another body, and 2 did not answer this question. Therefore 80% of the answers were provided from our EARTh membership. Thirteen of the study participants were female and 2 were male. Therefore, a weighty 87% of female representation.

This is not uncommon in the field of research within the therapeutic context.

One hundred percent of the participants answered YES to Question 1, indicating that as a practitioner they had experienced aspects of the process of regression therapy, which appeared to be ineffective, did not work, and/or presented particular difficulties. This, of course, is a naturally high percentage given that those who did engage in this survey were embarking on sharing problems they had experienced in regression therapy. This statistic should not be read to indicate that there are particular problems inherent within regression therapy, which, for example, do not also present themselves in other

forms of therapy. Therefore, the reader must bear in mind that as we explore the data provided on the lack of success with, for example, addictions and mental health conditions, what is not open for interpretation is that this data indicates overall failures with regression therapy itself. This is not a valid interpretation. Nor does it indicate a polarity of success via other traditional therapeutic practices such as classic psychotherapy. Many of the collected responses on difficulties and failures that are very common within all therapeutic approaches. As all therapeutic approaches continue to evolve and adapt new methods, new skills are integrated to mitigate against the most problematic of client presentations. This, of course, will also hold true in regression therapy. One can also bring consideration here to the foundational bias in the study in that it was in itself relating to ‘problems’ and hence one can perhaps determine that many of the non-respondents—95% of EARTh members—had not similarly experienced the problems explored in the body of this research report in their therapeutic practice.

Seventy three percent of the participants answered YES to Question 3, indicating that as a client engaging in regression therapy, they had experienced aspects of the process which they determined were ineffective, did not work, and/or presented particular difficulties.

Analysis of Question 2 Data – There was a collection of rich data pertaining to Question 2, and in relation to problematic aspects experienced in the research respondents’ practice of regression therapy with clients. The dominant theme determined from the answers was ‘Resistance’, and there was mild resonance on client presentations such as working with addictions. This overview of the responses begins with the answers which were unique to individual practitioners and flows towards those areas where there was a greater similarity between responses.

There were a range of singular responses to the research question which cannot be fully constellated within a theme. These include working with clients who do not really want to be there but have been persuaded by someone else.

One respondent shared, “Once a man came in for therapy because his mother wanted it so much. Of course, it didn’t work.” Another stated that some clients are “Just not ready for the work.” Whilst a further respondent said that they had experienced problems with a client who stopped communicating with her during the session and shared no words.

In the following excerpt from a practitioner an issue is shared which relates to clients who jump around in multiple past lives. The practitioner notes, “I have had difficulties keeping a client ‘on track’, staying in one past life without jumping around, even when I think my suggestions are clear.” Another difficulty shared by a respondent related to working with clients who only see colours and no fully formed images.

More than one respondent shared difficulties in terms of clients attending sessions with no clear goals or intent for the session. This was also linked with clients being unwilling to take on their own sense of responsibility for their side of the work. This also relates to clients who need to be offered realistic expectations and require their existing expectations to be measured.

These latter points are also associated with responses about the necessity to have a strong therapeutic relationship as a foundation for the work. However, the presence of such a relationship does not always equate to a good outcome if the client is resistant, as was noted in the following statement:

We had worked together for many months in a psychotherapeutic context so the therapeutic relationship, the trust and the containment were there as resources. The resistance was voiced during the initial phase of the session and we openly discussed this with no benefit. I tried to work with the emotions as a bridge but she got off the couch and sat in a chair, adamant that this was not a process she was willing to engage in.

Multiple respondents cited experiencing issues and a lack of success with clients who were under the influence of drugs or alcohol and/or have addictions, “It doesn’t work with people that don’t have a clear consciousness – drugged, dizzy, drunk..” Also, “In cases of addiction, especially alcohol addiction, I have had less success. After the session, the clients felt good…but the effects did not last. I think the slow progress was caused by deeper, tougher causes.” A further respondent stated the following: “Clients who have used drugs—they sort of do not pick up the transformation—as if they subconsciously want to stay where they are.” The following example combines the use of medicinal drugs and the presence of resistance, “The client took an extra dose of painkillers—so she could not feel anything. I did a bit of energy balancing with her. Only one consult, no real session.” In addition to these responses the following was shared about the need to integrate the body when working with addictions:

Hypnotherapy for stopping smoking doesn’t work (neither for alcohol addiction) until the core issue is resolved, simple hypnotherapy is ineffective. Resolution at the spirit realm and seeking or giving forgiveness does not happen until the issue is resolved in the body. The healing goes from the body to the spirit. If it is directed the other way around it does not have any profound effect. Emotions stuck with the body prevent healing of the spirit and the body. So, the body needs to be involved in every session. The hypnotic suggestion only provides a patch on the wound. The wound heals itself without being properly cleaned. For the healing to really take place the densest vibrations (physical) have to be worked with along with the more lighter (emotions, thoughts). The densest hold the key to the healing.

On another theme, one therapist stated:

From my experience Regression Therapy doesn’t work on a person that is not in contact with reality and is very fragmented—like psychotic clients, or very deep depression, or borderline, or people with paranoia, or is right after a very big trauma and in shock.

Indeed, there were multiple answers which noted a range of problems when working with clients who had significant mental health issues including a prior history of psychosis, paranoia and deep depression or were either in the midst of a current traumatic situation or just coming out of one. A therapist shared the following story:

I worked with someone that was under medication after a psychotic event. He was in remission. We worked only on this life’s past. It was very good and he was stable. At some point he says that he doesn’t need therapy anymore and he succeeded for a period to be stable with no medication. I told him to call if he needs more therapy. During summer holiday he went to visit Auschwitz and he decompensates having another psychotic episode. We worked a little (classical therapy), and being in a paranoia episode, he didn’t trust me, he left the therapy. I continue to work with his girlfriend (he also had couples therapy) in order to support his condition.

Regarding the area of trauma, the following was also shared, “A client could not go into a trance. She came in a traumatic situation which was related to her mother and was very disturbed about it.” And in another response, it was also noted that there was a serious resistance to accessing any material as a result of the trauma being very heightened.

Co-morbidity of pre-existing issues and being in the midst of current life stressful events was also indicated as creating difficulties in the use of regression therapy, for example:

I had a client that I helped to have more self-esteem, but there were dynamics in their current life that gave such amounts of stress that made this person so unbalanced that after the last couple of sessions they actually felt worse than before. I had to end the therapy, because I felt it had done more bad than good at that moment in time. This was very unsatisfactory for both of us, but it was the right decision, more regression would have made them more unbalanced at that time was my strong feeling.

In terms of depression the following comment was shared which conveys an interpretation of a resistant agenda to remain in the condition, “Certain deep depressive clients are afraid to come out of that state. Stubborn to remain in depression.” Another therapist shared the following narrative:

The client was on strong anti-depressants and feared she would heal and lose her support group in the psychiatric treatment after being healed and be lonely again. So, she chose to deny the results of her session… I have done energy work to balance her body and release some family charges, and we worked on cognitively understanding her situation and possibilities. But she did not want to heal.

Resistance – The prevailing realm of resistance was shared as a very problematic and difficult area in regression therapy by more than half of the study respondents. Resistance in many forms being the dominant theme in the answers to Question 2 and dramatically outweighing all other similarities in the data.

A significant number of practitioners spoke about problems either during the induction phase of the session or in relation to accessing any material or depth. This was interpreted in their answers as being linked to a multitude of reasons including fear, anxiety, problems with letting go, being too “stuck in their heads” or blocked. Here are some of the actual responses:

The client was a psychiatrist, who was freaking out for fear—and tried to keep himself away from trance-depth. Yet he went in the experience, but refused to take it seriously. I stopped working with him after this session, in which a few strong entity attachments were freed. (He had taken them over from a patient of his).

There was client that came for regression, entered it and could not bear to see what was there. We continue with classical therapy. At some point, she said it was too much for her and we stopped… she just wasn’t ready.

Client was a scientist who was extremely scared to let go of control, so he denied all he saw and did not give the information to the therapist. Therefore, we had a conversation in counseling style.

She saw beautiful colours she likes very much. Beautiful. Bright, different from earth. She liked it very much, but keeps seeing only colours, constantly changing. After the session: she says she won’t go to the problem because she is afraid to hear/know the answer.

When they are more on intellectual level the lessons or insights do not have as deep/life-changing depth so it stays on the surface. Ego resistance or mind resistance as if they may try to prove this tο themselves, that regression does not work. Also, as a therapist we should not have fear or doubt to go into deep issues and traumas, otherwise clients feel it. I also experienced strong resistance from a client in a current life regression session. The client had expressed a desire to return to key traumatic events from her past to bring about heightened awareness, transformation and healing. However during the session she refused to access any material.

While another respondent indicated forms of resistance under the banner of entity attachments and in their experience as practitioners they had made the following determinations:

I have had less success in cases of clients that came to me with quite large problems in their health, finances and luck, who were already sure that bad entities were causing this. Or with people who were in their own experience possessed by entities and wanted me to get rid of those. Now I do not take these cases on anymore. I have a strong feeling that the entities are not the problem, but underlying causes that they cannot deal with yet for whatever reason. The clients usually do not want to work with that, they only want to get rid of the problem by getting rid of an outside cause.

An additional realm of resistance presented itself in terms of clients who attend for regression therapy but do not actually have any belief in it, and where it conflicts with the client’s own specific belief systems. A practitioner shared the following scenarios, “Client was a firm believer in a certain spiritual theory, and dismissed any experience that was not in his framework—we switched to counselling instead of regression, for this reason. Only one session.” “Client was a psychiatric nurse—not willing to believe in any of her own experiences.

One session only.” In the following scenario we witness this conflict, resistance and also the benefits which can ensue if the resistance is respected:

On one occasion during a regression session a client very forcefully said to me from his conscious mind “This is not working”. He was experiencing a mental resistance. I could have stopped there and believed the session to be a failure. He was very alert and wanted to sit up, however I spoke to the resistance and was informed that he did not really believe in past lives and would be “making it up” should he continue. So I encouraged him to make it up, to just use his imagination. He continued to resist, “But what’s the point? It wouldn’t be true!” I continued, “So let’s say it’s not true, but let’s imagine what might happen”. Instantly he brought forward a meaningful and complex past life narrative! I worked with the ‘story’ as I normally would and no resistance was present. Conscious mind could relax and allow. After the session in our ongoing face to face therapy, without prompting, he worked through and processed the contents of the ‘past life’ and related them to his current life. The links he formed were very significant and transformational. He achieved his ultimate goals to be more empowered and assertive in his life and to find a new partner.

The Integration of Other Therapeutic Approaches – As evidenced in this latter scenario, many of the research participants reported not only examples of resistances, shared a range of methods they had used and approaches they recruited in to work with and respectfully attend to their clients’ resistance. For example, and as has been evidenced in some of the answers above, many practitioners had used other styles of practice including, counselling, traditional/classical therapy, energy healing and readings, which often served as supportive mechanisms and/or a bridge towards undertaking regression therapy. Additionally, the respondents variously noted a range of benefits including the building of trust in the relationship, the measuring of client expectations and the alleviation of anxiety which brought benefit to the client.

This integration of other approaches and honouring of the resistance was shared in the following examples:

One of my clients completely stopped communicating at one point, I couldn’t get a single word from her. But when I asked her if she wants to tell me and communicate with me, she nodded her head. I calmed her down and let her open her eyes, I knew she needs and wants to get rid of the problem. I asked her if she needs some time and asked her if she can write it down for me. She nodded her head again, she agreed that she will write it up when she is ready. I waited behind the door for her. Approximately after 15 minutes she came with full paper of problems with one of her parents. After she wrote it she was capable to communicate with me.

A client comes to me with relationship problems. We work a few classical sessions and in the fourth we do a regression. She sees her mutilated body and can’t bear it. We explore that life, but she can’t approach her death moment anymore. She opens her eyes. We didn’t close the session so that didn’t work totally, but I was in contact with her and didn’t push her.

The Making of Meaning – As has been noted above, most aspects of practice which the practitioners deemed to be difficult or even failures were strongly linked with client resistances. A large number of research participants attributed a range of personal meanings to these scenarios and used them as catalysts to bring greater understanding to their practice of regression therapy, and an awareness about their use of Self and their own intentions. Often sharing how experiencing problematic areas in their practice had not only taught them how to flow better with their client’s needs but had also brought about the development of new methods within the field of regression therapy:

In the early days of doing this work 25 years ago, I was so impressed with past-life regression therapy and had the determination to make this method work. I had a client who was a well-known television commentator, very handsome by the way, so his fame made me even more determined to make this method work. He was resisting so I persisted in asking the same question in a number of different ways. Finally, knowing that I was trying to force and manipulate him, he opened his eyes and said, “‘X’, you are a brat aren’t you!” The lesson, respect resistance. If the client is resisting there is a reason for it so go to the resistance, usually fear and/or control issues. Work with the issues and once the client understands that you are not going to force them, they then know they can trust you enough to enter the unknown.

More than 25 years ago I had an agenda. I believed that if the client regressed to and resolved the traumatic past lives then they would blossom into the true self, making conscious choice in ‘now time’ instead of reacting to traumas from past lives. I also believed that present life would be resolved entirely by doing past life work. I had a client who easily went into intense, emotional, passionate past lives. I worked with her for 6 months and we did ‘blood and guts’ work every session, almost every week. I could see positive progress in her life, confirming my agenda. One day she walked into my office, collapsed in her chair and looked at my hopelessly and said, “All these horrible past lives! Didn’t I ever do anything good?” That taught me to work with the client, stay with the client not my agenda, and more important, help the client build an inner foundation while taking down the coping structures by using regression therapy. This also led me to pioneering Inner Child Integration therapy. I understood that regression is regression and we have to go to the causal incidents regardless of past, present or alternative lives. With Inner Child work, I also found that we were able to build the client’s foundation as well as work more effectively with the present life body.

Interestingly, there were a number of examples of a very important reason why the resistance existed and/or ways in which honouring the resistance had proven to be very meaningful, fruitful and supportive for the client. For example, one male therapist shared the following story about a ‘failure’ with a client which was linked with him being over identified with a perpetrator:

A young woman came for help in her relationships with her family. She said she ‘hated’ them and then told me her history which included childhood sexual and physical abuse. Progress was very slow and appeared to be blocked. We discussed this and arranged for another session where we could explore this a bit more. She sent me a message saying that she did not ‘trust’ me and terminated the therapy. She did not respond to my reply either and it seemed to me that we simply did not get through to the core issue. She chose a man to work with yet the experience seemed to reinforce her lack of trust in men. My age and physical appearance may also have contributed to that.

And in the following narratives we can see evidence that what was believed to have ‘not worked’ was, again, actually very meaningful for the clients involved. The first example shows a therapeutic experience of abandonment, whilst the second conveys a very clear opening of the energy of trauma to be healed despite the regression therapy session itself being ‘unsuccessful’:

There was woman that came to one of my introductory workshops. She really wanted a regression. I sensed that was not right, but I made the appointment—we worked the interview for one hour and there was nothing that opened, only that I felt a very big pressure on my head. I told her—“I’m sorry but I can’t help you with this. We can’t do a regression, but we can do classical therapy if you want.” She went flat like a balloon with no air and I felt no pressure on my head. She had great expectations. I told her about realistic expectations and what we can do. After eight regular sessions, we finally met (in the 9th) and we did a regression. She was abandoned at birth by her mother—we worked that—that was very transforming.

The client had expressed a desire to return to key traumatic events from her past to bring about heightened awareness, transformation and healing…. Resistance was voiced during the initial phase of the session and we openly discussed this with no benefit…. This was not a process she was willing to engage in. I honoured that. I did feel a sense of failure and thought of what I could have done differently, done better. In our ongoing face to face work she never made any mention of the failed regression session. However, what was fascinating was that she began to attract a whole host of clients (she was a counsellor) who had experienced similar traumas to her and she also decided to write her Master’s Thesis on trauma! How I understand this is in effect the Universe finding a way to assist her to heal. That the energy of the trauma had been activated and in a curious and synchronistic way had brought forth the tools she needed to work through her difficult past. At times we must not have intention but attention. Not a fixing but a bearing witness to. With this lens of perception we cannot judge the work or ourselves to have failed or been ineffective as energy will always find its own way to flow.

To conclude this section of the report, and to embrace this concept of failure as being purposeful and containing a wealth of meaning, here is a rich interpretative comment shared by one of the research participants. “Trying to do something and not succeeding means something and sometimes is useful, so from my point of view there is no such thing as ineffective therapy….”

Analysis of Question 4 Data – Question 4 related to the study participants experiences as a client of regression therapy which were felt to be ineffective, did not work and/or had problematic aspects.

Not Attending to the Clients Practical Needs – The first theme constellates a range of experiences, in the answers to Question 4, which can be considered as ineffectiveness or failures in relation to the clients ‘Practical Needs’. These included problems in the sessions such as their therapist talking too quietly, not attending to the client being cold, creating gaps in the session due to the writing of notes, and the presence of external intrusions. For example:

In one session, the therapist spoke very quietly and it was difficult to hear her. This created an experience for me where I felt that my witnessing mind was being attentive to the volume of her voice which was to the detriment of the depth of my hypnotic state. I was aware of feeling freezing cold and starting to shake because of it—likely due to the depth of the regression experience. It would have been helpful for the therapist to place another blanket over me to support my needs.

In another session, I was aware of long gaps between my answers to questions and the next question. This was because the therapist was taking time to write up her notes. I felt as if she was not fully attending to my needs and the time delays and the lack of attentiveness of the therapist meant that certain past life memories were not fully explored.

Later I understood that there were other persons that wanted to enter the room and thus there was pressure to finish the session quickly.

Interestingly in these above cases, the clients had felt unable to inform the therapists that they needed to attend to their needs more appropriately, talk louder, provide them with another blanket and so on, which very much indicates the strength of the power dynamics at play within the therapeutic dyad of client and therapist. Hence a realm of practice which practitioners can reflectively bring into awareness in terms of the transference dynamics inherent within the therapeutic relationship. Additionally, perhaps it is the actual forging of a positive therapeutic alliance which would allow the client to express their needs and voice their concerns.

Not Appropriately Attending to the Clients Material – In this section of the research report a range of answers were provided which can be constellated under the theme of ‘Not Appropriately Attending to the Clients Material’. This differs from the practical deficits highlighted above and are more related to the therapists’ style of relating to their clients and how they worked with the material their clients shared during regression sessions, which may also be termed ‘relational deficits’. For example, a number of the study respondents experienced scenarios in which their therapists lacked an appropriate degree of attention to their needs due to the application of fixed approaches, the misinterpretation of what was being conveyed to them from their clients, just not listening, or not appropriately working with the energy or appropriately closing down the session:

I worked with a therapist on an issue where I felt as though he was just not listening to me. I needed to repeat a significant moment yet he still ignored it! It seemed as if he had a fixed approach, and my responses did not fit in with that.I think the most difficult and/or problematic experience I ever had in a regression session was when, rather than the therapist listening to what I was saying and following the experiences I was verbally conveying to him, he constantly interpreted back to me his own understandings of what was going on and conveyed a complete lack of understanding about what I was sharing with him.

Not every therapist is able to ask the right questions. And some forget the energy work.

While I was a student and we practiced among ourselves there was a student that did a session with me. Because she couldn’t close it she opened two more lives and left me during holiday with three opened lives. It was terrible, a lot of pains and fatigue—it was the worst holiday ever.

The deficits in some of the sessions which the study respondents experienced as clients were so difficult that they expressed either being glad when the session was finished, “I gave her the answers she’d like to hear to get out of that session ASAP,” empowering themselves by taking control of the session, “I pretty much direct my session the way I needed, so I was able to pick up on what was missing for me and tell the therapist,” or even ending the session:

I was then in a position where I had to correct him as due to his lack of understanding and misinterpretation he continually guided me in very strange ways to areas which lacked any energy and importance in terms of my needs, the character or the story. The experience was so exasperating that I sat up and brought myself out of the session.

This realm of empowering discernment was also embraced by one research respondent who stated that “No” she has never experienced any difficulties as a client in a regression therapy context because “I choose good therapists!”.

Self Reflection/Self Awareness – Just as a number of the study respondents in their addressing of Question 2 conveyed a degree of awareness about themselves and how they practice, this was similarly found in the answers to Question 4. Whereby, many of the ‘practitioners as clients’ had reflected upon aspects of themselves, and had brought in an interpretative understanding of this likely contributing to their problematic ‘client’ experiences. For example, two respondents shared the following: “I tend to feel much more than I see, and that can sometimes be a challenge to my therapist colleagues,” and, “To go in and trust the experiences, feelings—imaginations and pictures can be the first blockage.”

This realm of self-understanding and reflective awareness is a key aspect in the purposefulness of qualitative research and can bring to mind areas which require development in order to learn and to evolve. So, as we see here, the study respondents bringing awareness to their need to feel more and trust their experiences.

This process of evolutionary learning was also indicated by one respondent who noted that as a client they were very accommodating to their therapist, wanted to be a “good client” and stated that the benefit of this experience was that “These experiences helped me to be attentive that my own clients do not do the same.” This trajectory towards change is also witnessed in the following statement:

My problem as client was that I just didn’t know what the problem is and I couldn’t figure out what the real problem was. Regression therapy didn’t seem to work with that deep “I don’t know what the problem is” feeling. It was behind a veil and I just didn’t recall it. Long term sessions helped a lot and it took few years for me to get rid of this problem.

Concluding Reflections on The Research Material – The intention of the “What Doesn’t Work in Regression Therapy” Research was to determine if there were any prevailing themes in the answers to questions about experiences, as either therapists or clients, which would encourage self-reflection, inform practice and contribute to the body of knowledge of regression therapy. As has been shared above, the data communicated by the participants offered rich and meaningful content and allowed for a purposeful analysis which has indeed allowed for reflection, a heightened awareness of practice and offered a contribution to the knowledge base of the field. While a number of the answers were unique in focus, there was an ability to collate the data into the dominant themes of Resistance, The Integration of Other Therapeutic Approaches, The Making of Meaning, Not Attending to the Clients Practical Needs, Not Appropriately Attending to the Clients Material and Self Reflection/Self Awareness.

The Research Committee offers thanks to all of the practitioners who participated in this study and offered their time and effort. We are also hopeful that readers of this report will benefit from its content and reflect upon their own therapeutic journeys through regression therapy as both therapists and clients. The prevailing aim being: to embrace and continue the successes in practical and process driven ways within the practice and experiences of regression therapy, while also acknowledging the meaning-making potential of the failure-success pole.

To try and not succeed allows for progress. But how are we to determine whether or not our failures had a deeper meaning, which was at that point outside our realm of awareness, but was inherently purposeful to our clients and/or ourselves as practitioners? Perhaps this realm of unconscious to unconscious transference dynamics within the client therapist relational pairing is an area worthy of further consideration in terms of the purpose and attribution of ‘failure’ and its multi-layered projections of blame.

Concluding Reflections on The Research Protocol – Undertaking qualitative research involves reflexivity: a reflection upon the process itself, areas under question, or realms which could have been improved. The benefits are often not about knowing the answers but more about being able to formulate the right questions and bringing them into reflective awareness. Regarding this particular research protocol, one major area under consideration is the low number of respondents (only 5% of the EARTh membership). Was this due to most practitioners dominantly experiencing success in their practice of regression therapy? Was it due to language barriers? Was there no energy for this particular topic? Did the open request to participate lack a motivational charge to encourage participation? Was the structure of the research collection method (questionnaires) too impersonal and was the open-endedness of the questions too fluid? Could this qualitative study have been improved by an alternative method of data gathering such as face-to-face semi-structured interviews or focus group participation? The Research Committee will direct attention to these questions as we progress towards future research studies.