by Vitor Rodrigues, Ph.D.

This article presents a scientific and clinical discussion of how memory is fundamental to our concepts, our experience and the workings of our mind, to explain – for readers concerned with possessing a body and a mind – how and why regression therapy works. After defining regression therapy, this article follows with a general perspective on how it is done, what are its pitfalls, and how to avoid them. It presents a theoretical perspective on how and why it works, and why it can overcome criticism based on studies about how memory can be biased, can be distorted and can be fabricated.

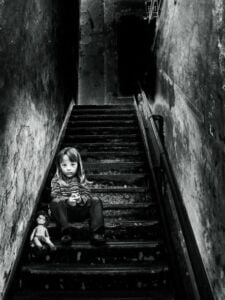

It is a well-established fact that trauma produces powerful behavioral consequences along with strong and very emotional memories. We discuss brain mechanisms of stress-related effects, research on flashbulb memories, and how research shows that memories may be forgotten at the conscious and rational level, while still influencing us at less conscious layers of the psyche. A perspective on traumatic effects as being similar to ‘computer viruses’ is presented, followed by three cases illustrating work on sexual issues.

Regression Therapy has been around. One could think Regression Therapy only recently became fashionable, but it has a considerable history, at least since Denys Kelsey and Joan Grant published their work in 1968.

However, many authors and practitioners in the vast area of Psychotherapy still are suspicious about it. First, regression deals with memories—and memory mechanisms can be tricky, as we will discuss. Second, apparent past lives may pop up. Third, regression therapy can be spectacularly effective so it may incite professional jealousy.

What is Regression Therapy?

One could say that it consists of a methodology to help people connect with their past: (1) to get insight in the origins of psychological suffering or disturbances; (2) to use this insight for ‘reprogramming’ the mind, changing relevant behavior and reframing life. Underlying this, we find the general assumption that past events, learning experiences and traumas do shape and condition who we are, what we are sensitive to, and what limits us. Many of its practitioners assume that Past Lives are one big part of the whole thing. Regression therapy procedures, that belong to the general field of Transpersonal Psychotherapies (see Rodrigues & Friedman, 2013), typically induce changes in the state of consciousness of clients, taking them towards expanded states in which the quality of the inner experience changes either quantitatively: more intense, vivid or enlarged perception of normal stimuli; or qualitatively: access to a different perception of stimuli or even to different contexts, both present or past.

To achieve this, therapists can resort to techniques such as hypnosis, ‘exaggeration’ of body symptoms, repetition of word formulas that encompass strong emotions, construction of inner ‘virtual’ realities to be used for this purpose, and building bridges towards the past in many ways. Sometimes clients will get in touch with emotions, perceptions, and vivid descriptions, concerning what they perceive as previous lives. However, many therapists don’t consider it necessary to ‘believe’ in these and doubt whether these phenomenological experiences correspond to ontological truth. They may be just powerful emotional metaphors helping clients reframe their emotional life and may be useful despite any proof of being ‘accurate memories’.

Generally speaking, the client will be helped by a therapist, working as a catalyst, finding inside himself the memory he needs to deal with, not as a ‘distant’, cognitive recall, but as a vivid re-experience with emotional content. The therapist will help the client deal with whatever came to the surface—if it will be ontologically true or not and if it concerns infancy or a past life. What matters is emotional relevance, symbolic power and usefulness in the quest for new meaning and healthier behavior.

Freedman states, “we do not yet know whether past life stories are memories of actual past lives that people have lived, or creative fantasies, but we do know that whatever they may be, they are usually extremely and rapidly effective in therapy for a wide variety of conditions. Healing stories, indeed.” (2007; quoted by Zahi, 2009, pp. 266-67) Nevertheless, some high-quality, solid evidence supports the possibility that neither reincarnation, nor Past-Lives Therapy are so far-fetched as they may seem to many authors (Stevenson, 1997a, 1977b; Woolger, 2004).

Going through it

A careful evaluation of the clinical condition of the client is mandatory before a session is done. This is necessary in any therapeutic approach, but even more here because strong catharsis may happen and because the client can, for some time, be less connected to the ‘here-and-now’ reality of his surroundings and of his body. Therefore, severe cardiac patients and patients with hypertension are not good candidates. Neither are clients with an impaired sense of themselves and their body, such as psychotic patients. This also depends on the particular situation, the advice of other clinicians (e.g., cardiologists) and the special experience and preparation of the therapist.

To experienced therapists, many techniques can induce regression, including varieties of EMDR and—for clients with special previous mind trainings—very direct entries such as focusing inside, picturing a ‘time-hole’ and diving into it to connect with the origin of an emotional trouble. The experience of the therapist is quite important, but so is the experience of the client.

When the session eventually unfolds, the therapist helps the client to explore his past in search of the origin of his clinical complaint. Once it seems that some situation or set of situations from the past (usually after exploring several that the client has brought up spontaneously) is the fundamental origin of the problem, the therapist helps the client to explore how this situation produced a particular emotional pattern, a particular mental program, or even some body ailment that is still troubling him today.

The client is stimulated to produce some new meaning, some re-programming, some way out that will help neutralize the past without forgetting it. We don’t want the client to forget, but to gain some new wisdom and strength from the whole experience. Of course, the way to manage a session depends on the therapist’s expertise and options: some have favorite techniques, some will make sure that each relevant situation is explored and re-programmed, while others (like the present writer) may focus on the ‘cognitive-emotional systemic knot’ of the single most important single situation and then, once it has been untied, expect the whole ‘personal system’ of the client to start changing.

A session is never ended without making sure that some closure has been achieved and that the client experiences release, new meaning, or a positive conclusion. We don’t assume that catharsis is enough by itself. Just re-experiencing a traumatic situation, for instance, could facilitate the corresponding neuronal pathways and even worsen the symptoms. Therefore we make sure that the client finds some productive way out of what he found.

Some technical cautions

Good hypnotists, as well as regression therapists in general, know very well that it is pointless, and maybe damaging, to project their own fantasies assumptions or expectations on clients. So, when clients are in an altered state of consciousness – with enhanced suggestibility – the handling of the inner exploration is extremely important. So we ask, ‘What just came to your mind?’ Or, after observing a facial expression of disgust, ‘What is it that just produced some unpleasant feeling?’ We never ask things like ‘Is it an abuser?’ or ‘Is there some green man in the situation?’ because we would be the ones putting them there.

In the same vein, if a client says he is just feeling afraid, we may ask questions like:

- Do you know what this fear is about?

- In the moment you are feeling this fear, are you in an open space or inside some closed place?

- Do you have the impression that it is morning, night, afternoon?

- Feel this fear. As you are feeling it in the situation, are you standing, sitting, lying down?

- Are you alone or is someone else with you?

Sometimes the session just unfolds by itself and the client spontaneously gives lots of detail. In this case, the therapist intervenes as little as possible, perhaps just asking for clarifications. ‘Do you mean that the pain comes from a wound? Or is it coming from something else?’ Suggesting alternatives for answers help the clients feel there is no definite expectation and no pressure about what they ‘should’ be feeling or answering, and that they are free to bring on their experiences. We have special questions for special difficulties the client may be experiencing: ‘I don’t know.’ ‘What if you knew? What would be coming to your mind?’

We may indeed ask clients to imagine a story about someone with a trouble like theirs, but this is only a last resource when other techniques are not working. Of course, we would not assume that this ‘story’ corresponds to facts as it may just be a fabrication, though with relevant emotional content. Helping the client find a different, positive ending to a traumatic story can be a good idea, with possible positive results.

Theoretical considerations

Regression therapy deals necessarily with memories and how they may be damaging the client’s present day behavior, emotional life, worldview and so on. There are some caveats.

First, some authors have shown that memory may not be accurate and that we do change the way we remember facts. Thomas, Hannula and Loftus (2007) underlined the researched fact that, although imagined rehearsal of healthy future situations can improve behavior and produce good clinical results, it may also distort memories of past situations. “Unfortunately, those aspects of imagination that have been shown to be important for behavior change are the same as those that have been shown to lead to dramatic distortions in memory.” (p. 71)

So, if a given client is asked to imagine a plausible scenario for behavior change, it might affect his behavior, but it could also distort his memory. The authors have shown that this can happen when we resort to guided imagination to get therapeutic results. Subjects may change their memory of target behaviors if they imagine them improving, for instance. This occurs the most when imagined behaviors are self-relevant (i.e., the subject imagines himself performing them and finds this relevant). They later may wrongly remember their original scores in the target behavior. The quoted authors posit, “Implicit theories may affect memory by influencing the kind of information retrieved from memory as well as the individual’s understanding of that retrieved information.” (p. 83)

Most people emphasize the stability and unity of themselves through time as they see themselves in the past doing things or interpreting things consistent with how they do things and see things today.

This line of research has been probably the most powerful source of criticism on regression therapy in general, even forgetting that, as in any other area, there are competent and incompetent therapists.

In the eighties, people have been accused of sex crimes they never committed, based on false memories of supposed victims, while some real victims of sexual abuse were not believed. Ornstein, Ceci and Loftus (1998) wrote a good review about this. They underlined the issues we face when considering how we remember things.

In the first place, information may or may not be stored. It may be stored more or less accurately, its intensity and quality may change, and it may be influenced by knowledge and expectations. Obviously, the quality of representations also depends on how we interpret events. Recall may also be distorted as we rebuild our memories and interpretations over time. The repetition of events and their emotional intensity and relevance obviously play an additional role. Lastly, the recall of events tends to fade away with time.

Ornstein, Ceci and Loftus strongly caution about the suggestibility of memories and the dangers of inducing (even unintended) new or distorted ones, a possibility. Loftus (1994) demonstrated in many very convincing and experimental ways. “We may even ‘inject’ false memories in naive subjects through manipulation.” However, she admits that traumatic events may be not so easy to manipulate or change as neutral ones, since traumas tend to produce very intense memories.

Laney and Loftus (2008) conducted research showing that even emotional content is not at all a sure way to distinguish true from false memories. Some people assume that the intensity of emotions gives credibility to memories. In their research project, they could induce ‘memories’ of fake events in naïve subjects, like being hospitalized or catching their parents having sex. Emotional intensity of memories doesn’t guarantee their credibility.

Meyersburg, Bogdan and McNally (2009) even concluded that, although they showed no differences in correct recall or intelligence, the subjects with supposed, ‘improbable’, memories of past-lives showed bigger rates for false recall and recognition than the control group who reported but one life.

However, all of those criticisms should be weighed against other evidence. For instance, according to Ellason and Ross (1999), one core symptom in post-traumatic stress disorder is the dissociative reliving of the traumatic scene as if it is still happening; another important symptom is the tendency to re-enact the whole thing. This may happen directly or more symbolically. In the authors’ research, 92% of patients with sexual trauma showed evidence of dissociative disorders. This was also true for 77% of sex offenders, implying that early childhood sexual trauma might often be at the origin of sexual crimes.

Nijenhuis et al. (1998) found, in a correlation study, that subjects with dissociative disorder revealed severe and multifaceted traumatization; physical and sexual trauma were predictors of somatoform dissociation while sexual trauma alone predicted also psychological dissociation. Early onset of severe, multiple, chronic traumatization was predictive of more pathological dissociation. The authors describe a special type of dissociation: “somatoform dissociation, i.e., dissociation which is manifested in a loss of the normal integration of somatoform components of experience, bodily reactions and functions (e.g., anesthesia and motor inhibitions).” (p. 713)

They also note that preliminary data shows that fantasy proneness and absorption may be higher in traumatized patients when compared with the non-traumatized. So indeed, this also should be weighed against the research discrediting regression techniques because of the fantasy proneness of clients. Many authors have shown that sexual abuse can produce severe disturbances including somatoform complaints and dissociation.

Nijenhuis et al. (1998) concluded, “somatoform and psychological dissociative symptoms are primarily tied to reported severe, as well as chronic physical and sexual abuse, which according to the subjects started at an early age, and occurred in a disturbed and emotionally neglectful family of origin.” (p. 727)

Diseth (2005) mentioned research literature showing that neurological factors can also predispose to dissociation. They include repeated minor cerebral traumas in early childhood and mild traumatic closed head injury in children. However, the most important predisposing factors are still in the line of trauma from emotional maltreatment and neglect, emotional and physical abuse and, of course, sexual abuse.

Diseth (op. cit.) mentions the negative effects of prolonged stress on the brain of developing children as the increased levels of cortisol can produce toxic effects. Such effects are particularly severe in early life as they might reduce cell migration, glial mitosis, myelination, atrophy of dendrites and early degeneration or death of neurons. In turn, the affected areas in the developing brain are those with many glucocorticoids receptors, such as the limbic system and the neocortex, but also the hippocampus, known to have a key role in memory.

In detail, observed consequences of prolonged stress to children’s brains include:

- a pathological response from the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis (HPA), including a down-regulation of the production of cortisol that could account for abused children’s inability to react to threats as they just manifest a passive fear;

- a pathological sympathetic and catecholamine response (increase in secretion of noradrenaline and dopamine) that could correspond to prolonged stress and intense responses to minor situations somehow connected with the basic traumatic ones;

- a parasympathetic nervous system response that could account for dissociative symptoms. During a frightening, inescapable situation, the child could dissociate from the actual reality. The activation of the vagus nerve by noradrenaline would slow heart rate and bring down blood pressure; the increased release of endorphins in the brain would, in its turn, account for loss of attention and disengagement from reality.

In general, prolonged stress produces alterations in general brain functions, particularly higher activity in the right brain hemisphere, mostly in the areas connected with emotional arousal, while the Broca area in the left hemisphere is mostly turned off. This last fact helps us to understand that children have mostly physical memories instead of verbal ones when re-experiencing a trauma. Also here, regression therapies may be a lot more helpful than general verbal ones, as they appear to bring easily pre-verbal memories.

Limbic system dysfunctions are also found. Structurally, there may be a reduction in total brain volume, specifically in the corpus callosum, hippocampus, amygdala and left prefrontal cortex.

Critics of regression therapy rarely take into account something quite familiar to regression therapists: there may be several layers of contact and memory building for the same experience and one can access them through consciousness change techniques. A memory could be distorted at one level, but found intact at another, as if several imprints of the same event did happen simultaneously at several levels or structures. We also know that memory retrieval is ‘state specific’—and this state can be both the emotional and the consciousness state.

One woman was suffering from extremely severe general amnesia after major brain damage, but could still recover memories from her recent life and her past as a three-year old child under hypnosis—a fact that we could corroborate with her parent’s independent testimony.

Loftus, Garry and Feldman (1994) concluded that many people can in fact forget past situations of childhood sexual abuse. The same can happen, already one year later, with reports of car accidents or other traumatic situations, showing that such forgetting is not exclusive to sexual trauma.

From clinical experience we know that it is possible to help such people retrieve lost memories and deal with them therapeutically.

Another area to be considered when we deal with memory issues is research on flashbulb memories. According to Davidson et al. (2005), flashbulb memories are vivid, enduring memories of surprising and shocking events. Flashbulb memories involve both memory of the event and its source. The authors found evidence for probable roles of specific brain areas in the formation of flashbulb memories and also recognized that ‘flashbulb situations’ produce more accurate and consistent memories.

While most studies of flashbulb memories involve public events, they may also concern private ones (Thomsen & Dorthe, 2003). In both cases, they are ‘more likely to be formed when an episode is important, emotionally intense, and unusual’ (op. cit., p. 566). So their phenomenological relevance would be more important than their consistency over time.

Bohannon, Gratz and Cross (2007) reviewed several studies on flashbulb memories, with their characteristic of being vivid and formed during shocking events. These studies attempted to explain how much they are reconstructed later and to which extent strong emotions produce strong engrams. This last aspect remains undisputed: emotion—particularly shock—produces strong memories that may be consistent over time.

The authors show that the source of the shocking event may be important in the formation of memories that are more accurate (media, with details and neutral information as sources) or more personalized and eventually less precise (persons as sources).

In the same line, Lanziano, Curci and Semin (2010) concluded that emotional states contribute powerfully to the building of strong memories, be it about specific items or the context of events. “People have vivid recollections of when they heard the news, where they were, what they were doing, and with whom.” (p. 473)

However, reconstruction processes also affect those memories, so that their accuracy may not correspond entirely to its apparent vividness and detail. They mention the ‘Now Print! Theory’ by Livingston (1967), who asserted that an underlying neuronal mechanism would serve an evolutionary function, helping ancestors identify dangerous situations and remember their environmental correlates.

In an experiment, the authors demonstrated that subjects can from an emotional situation indeed retain details that are both relevant or irrelevant, central or peripheral: both the event and its context. However, such details may upon recall of the events be affected by reconstruction, based on schemata available to the individual and the search for congruency. Therefore, the authors conclude that exposure to an emotional event produces both direct and indirect effects on memory. Both immediate, direct imprint and later elaboration influence what will be recalled.

Flashbulb memories are a typical example of how traumatic situations can produce powerful memories, even if there is no guarantee of their accuracy. In the next section, we will be talking about some theoretical implications.

The glasses we use: early life emotional tones, trauma and ‘computer viruses’

The glasses we use: early life emotional tones, trauma and ‘computer viruses’

Obviously, we build cognitive and emotional structures partially on the basis of our experience. Our earliest experiences pave the way for how we construct our vision of the world along with our identity. We also know that love deprivation (from neglect or with physical and sexual abuse) can produce later poor mental and physical health, in the same way abundant love and loving care produce its opposites: better general health and resilience (Rodrigues, 2008).

David Chamberlain (1998) has shown convincingly that we do develop extremely early memories that may be recovered even in adult life—and of course influence it. We know (see section above) that the earlier the abuse (sex or violence or both), the stronger the later emotional and behavioral disturbances.

Our own clinical experience goes in the same direction and we can add something: clients in regression therapy describe sometimes pre-natal, perinatal or events at a very young age, even past lives. And whatever the accuracy of their recall, clinical benefits are often obvious. How and why?

We have observed many times that, when clients recall emotionally traumatic events, they are surprised to find out they forgot very relevant details. They may have vivid, spontaneous recall of painful, violent or scaring events, but many times, they forgot the way they interpreted them.

For instance, one of our clients could recall seemingly completely the sequence of a car accident, but had forgotten the moment he turned back and saw the wreck of the car he just had left, some ten seconds before it was bursting into flames. He had forgotten how he thought, ‘Driving can have you dying in flames.’ Later he could not explain how he became too afraid of driving, as previously he loved it. He knew it should be related to the car accident, but could not explain why, since he recalled a benign accident he, along with the driver, came out of unscathed. It is a well-known research fact that emotions are at least partially the product of evaluations of stimuli. Of course, this can be a fast, automatic and unconscious process (see f. i., Scherer, 2000).

During therapy, many clients re-experience some situation or cluster of situations with strong emotional relevance and then, only when in an altered state of consciousness that allows them to do so, they understand how they produced some idea or emotional and physiological pattern that later deeply conditioned their emotions and even how they perceived the physical and social world. This amounts to say that they somehow program their later emotional symptoms, as a sort of ‘computer virus.’

Usually, we only suspect ‘computer viruses’ somewhere in our system because of changes in the behavior of the computer like making it fuzzy, slow, losing information and so on. We suspect something, but we don’t know what it is, how and when it entered our system. With ‘cognitive-emotional viruses,’ we also know there is something wrong with our behavior and our feelings, but we don’t know where this is coming from or we don’t know in what way. In traumatic situations – when our emotional agitation tends to produce strong memories but also prevents us from using cold logic or being scientific about it—we produce many times a kind of lesson, a sort of ‘moral of the story’ that later becomes our ‘computer virus’. It can be something like ‘I will never trust any men’ (after being deceived by a fiancé) or ‘people are bad’ (after repeated physical abuse) or ‘dogs are awful’ (after being bitten by a dog).

The main point here is that later we may forget the detail that is emotionally most relevant – and then it doesn’t matter how accurate are the other data in the memory. Sometimes it seems as if our body has become afraid of something, like the needle that extracted our blood when we were babies; the spoilt milk that produced an almost deadly diarrhea.

To our knowledge, only regression therapy of some kind will later help deciphering the riddle of how and why we have such ‘gut reactions’ to situations—as may happen with phobias. It becomes of the utmost importance to recover memories and past experiences that may not be accessible to verbal therapies or even some somatic approaches, and also because the part of reprogramming after getting rid of the ‘computer virus’ is fundamental. We must help the client re-think, re-build his vision or feelings, and so ‘purge’ the virus from the computer system. In this way, we may compare regression therapy to an anti-virus program.

To illustrate the previous discussion, let us describe some clinical examples of what regression therapy can accomplish with sexuality.

Case 1: Hypertension

Martha was a 56-year-old married woman, working in a shop and usually showing an assertive personality and a positive attitude. She did have some issues with her husband, some conflict, but a normal sex life. She wasn’t manifesting depressive or anxious or dissociative features, although she didn’t seem very aware of her body. She complained of ‘essential hypertension,’ and this led us to extreme caution in dealing with her, first checking her medication and her blood pressure. For two years, it was around 12:16 [120/90], too high, even with medication. So our first sessions only dealt with relaxation, trying to bring the blood pressure down. She dropped to 11:15 [113/83], but no better than this.

We suspected that some unconscious motive might be underlying her trouble. We decided to conduct a very careful regression therapy session, always ready to ‘bring her back’ in case of a strong emotional episode. She then unexpectedly reported an episode of sexual abuse, from her uncle, when she was aged four. This helped her to tell and to express what happened and exploring the emotional and physiological consequences.

One week later, she had stopped her medication and had stable blood pressure at 8:12 [90/60]. It remained like that, allowing us to think that probably this major improvement was related to the clinical session. Of course, we wouldn’t trust this memory to hold up in court—but Martha wasn’t interested in bringing charges against her uncle. She was quite happy with the therapeutic results.

Case 2: The Gunman

Therese was a thin, tall, elegant woman in her thirties, working as an architect. She had no depressive or anxious symptoms in general, but she was very suspicious of men, tending to become aggressive towards any (even gentle) advances from them, keeping them at a distance. She did feel attracted towards men and even had a boyfriend with whom—this had been an exception—she could feel pleasure and even sometimes achieve orgasm. However, her general distrust was showing even in this relationship and it was difficult for her to deal with sexual issues.

Several sessions were necessary for her to develop some trust in us and allow herself to relax somewhat. Finally, during a successful session, she saw herself as an old, big and heavy American cowboy. She felt even his large mustache, the way he balanced his big body—and the way he abused women and took advantage of them, humiliating and abandoning them.

At the end of the session, Therese was surprised how intensely she had felt this different body – and also had understood that she was actually distrusting men because of her own ‘inside man’ from the past, who had been severely abusing some women. We helped her process this experience and somehow forgive her ‘inner man.’ We cannot say that this was factually a real past life, but this session was followed by important improvements in her relationship to men in general and more specifically to sex life.

Case 3: the Grandfather

Mary was a successful teacher, aged 40, divorced, with two healthy children. Being an elegant, attractive lady, she had easy success with men and managed to have a rewarding sex life. The complaint that brought her to therapy was depression. Her depressive symptoms were serious: she had a medical leave from her work, felt very sad, with feelings of worthlessness even though obviously having a successful career. She was working on her PhD and was quite popular among peers.

During therapy, we resorted to regression as she had no clues about the origins of her suffering, besides a poor relationship with her mother that also wasn’t understandable from events she could recall.

During the first sessions, she described an episode of childhood abuse. At first she only saw a male figure that scared her and made her feel sick. Later she identified it as being her grandfather, who had sexually abused her at age six. We helped her process this episode and she thought she could forgive her now deceased grandfather. She felt better and decided to stop the therapeutic process a few sessions later, even declaring that she had the feeling that later something else would need to be understood. She got back to her teaching job and work on her PhD.

About one and a half years later she came back, feeling depressed again. This did not surprise us, as she had interrupted the sessions too soon. Now she was determined to go wherever she had to, so that she would get rid of the depressive feelings. She was a determined woman. This time she allowed herself to dive deeper and allow any contents to become conscious. She described how her grandfather abused her for years, from a few months of age until she was close to seven. He had her to perform oral sex on him many times. She felt resentful towards her mother, whom she suspected had also been abused by her grandfather when she had been young. Her mother would allow the grandfather to ‘take care of her’ when she went for work.

She kept the abuse to herself as she felt hopeless, betrayed by her mother, and with no way out. This was connected with the depressive feelings. As a child, she did not know how to break the cycle of abuse as she was too young and dependent on her mother and her grandfather. She felt hopeless and, to some extent, worthless and polluted.

As part of the therapy, we helped her find her inner health resources and understand that although her body had been abused, her soul had been unpolluted and out of reach. She could also find her way to forgive her mother and get rid of her grandfather’s traces at last. She got a lot better after this and to our knowledge she still is. Even after the first therapeutic series she had felt more alive and able to enjoy life—and now this was even better.

These three cases illustrate how regression therapy can help to deal with half-remembered sexual abuse. We can use it to uncover hidden, forgotten or repressed contents and to help people deal with them therapeutically. We may access contents that are normally not available to the usual forms of conscious, verbal processing and memory, and so help clients to rebuild their views about themselves and find new meanings and new life decisions.

Especially when dealing with sexual trauma, regression is useful, since in normal, conscious and rational states of mind, many people have a hard time recalling and expressing such memories. Painful and shameful sexual memories are among the hardest to access and retrieve, particularly because— as we saw before, our mind can easily distort or dismiss them—and many times does not even allow us to start a quest that may unveil the unthinkable. So this is another, very important, area, where Regression Psychotherapy helps people rebuild their relation with themselves, other people and the world they are living in. And specifically the relationship with their own bodies, who may have become unacceptable after abuse and ‘pollution.’

Regression psychotherapy is an anti-virus program. And sometimes it is homecoming in our own life, in our own body.

References

Bohannon, J. N., Gratz, S., & Cross, V. S. (2007). The effects of affect and input source on flashbulb memories. Applied cognitive psychology, 21, 1023–1036.

Chamberlain, D. (1998). The mind of your newborn baby, Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Davidson, P. R., Cook, S. P., Glisky, E. L., Verfaellie, M., & Rapcsak, S. Z. (2005). Source memory in the real world: A neuropsychological study of flashbulb memory. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 27, 915–929.

Ellason, J. W., & Ross, C. A. (1999). Childhood trauma and dissociation in male sex offenders. Sexual addiction & compulsivity, 6, 105-110.

Grant, J., & Kelsey, D. (1997). Many lifetime (first edition 1968). Alpharetta, G.A.: First Ariel Press.

Laney, C. & Loftus, E. F. (2008). Emotional content of true and false memories. Memory, 16(5), 500-516.

Lanciano, T, Curci, Antonietta, & Semin, Gun R. (2010). The emotional and reconstructive determinants of emotional memories: An experimental approach to flashbulb memory investigation. Memory, 18(5), 473-485.

Loftus, E. (1994). The repressed memory controversy. American psychologist, 443-445.

Loftus, E. F., Garry, M., & Feldman, J. (1994). Forgetting sexual trauma: What does it mean when 38% forget? Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 62, No. 6, 1177-1181.

Meyersburg, C. A., Bogdan, R., Gallo, D. A., & McNally, R. J. (2009). False memory propensity in people reporting recovered memories of past lives. Journal of abnormal psychology, 118, No. 2, 399–404.

Ornstein, P. A., Ceci, S. J., & Loftus, E. F. (1998). Adult recollections of childhood abuse: Cognitive and developmental perspectives. Psychology, public policy, and law, 4, No. 4, 1025-1051.

Rodrigues, V. (2008). L’Amour, la Santé et L’Éthique. Synodies, Automne, pp. 36-45.

Rodrigues, V. & Friedman, H. (2013). Transpersonal psychotherapies. in Harris L. Friedman, & Glenn Hartelius, (Eds.). The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of transpersonal psychology, pp. 580-594 Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Scherer, K. (2000). Psychological models of emotion. In J. Borod (Ed.), The neuropsychology of emotion. pp. 137-166, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stevenson, I. (1997a). Reincarnation and biology: A contribution to the etiology of birthmarks and birth defects. Vol. 1, Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Stevenson, I. (1997b). Birth defects and other anomalies, Vol. 2 Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger.

Thomas, A. K., Hannula, D. E., & Loftus, E. F. (2007). How self-relevant imagination affects memory for behaviour. Applied cognitive psychology, 21, 69–86.

Thomsen, D. K. & Berntsen, D. (2003). Snapshots from therapy: Exploring operationalisations and ways of studying flashbulb memories for private events. Memory, 11 (6), 559-570.

Woolger, R. (2004). Healing your past lives, Boulder, CO: Sounds True, Inc.

Zahi, A. (2009). Spiritual-transpersonal hypnosis. Contemporary hypnosis, 26(4), 263–268.