by Ann Merivale

Since most of most people’s previous lives tend to have been rather boring, it is fairly unusual either to regress someone to, or to find oneself in, the life of somebody famous. Roger Woolger once did a session with a client who was filled with guilt as he was convinced that he had been the captain of the Titanic. The author of this article, who is a writer as well as a Deep Memory Process therapist, was initially surprised to find that she had once been well known as the ex-fiancée of a great English composer. She was later astounded when a reader of her book on this topic contacted her to say that he believed himself to be a reincarnation of this same composer. A moving story.

Since most of most people’s previous lives tend to have been rather boring, it is fairly unusual either to regress someone to, or to find oneself in, the life of somebody famous. Roger Woolger once did a session with a client who was filled with guilt as he was convinced that he had been the captain of the Titanic. The author of this article, who is a writer as well as a Deep Memory Process therapist, was initially surprised to find that she had once been well known as the ex-fiancée of a great English composer. She was later astounded when a reader of her book on this topic contacted her to say that he believed himself to be a reincarnation of this same composer. A moving story.

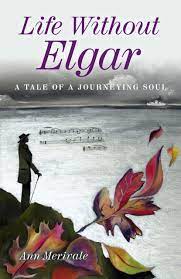

I should like to recount a fascinating story that occurred only last month (July 2016) as a follow-up to one of my books, and from which I am still reeling. When in life one gets a strong prompt to do something, the reasons for it are not always immediately apparent. If, while I was starting to write Life Without Elgar – A Tale of a Journeying Soul, anyone had told me that the book’s main purpose would be to give some healing to the great composer himself, I would certainly not have believed it! While I was enjoying writing that book, the most interesting thing for me about it was how the middle section—consisting of imaginary correspondence between Sir Edward Elgar and his first love, Helen Weaver—wrote itself. The letters had started coming into my head, completely unexpectedly, immediately upon my return from a meeting held in the room that had been Elgar’s own study when he lived at Plas Gwyn, Hereford, between 1904 and 1911. I then continued ‘channelling’ them over the next week or so and, since I was travelling at the time and do not own a laptop, that entailed scribbling in longhand on both trains and aeroplanes. Only after feeling the correspondence to be complete did I write the introduction to the book and then complete the sandwich with an autobiographical first section and a third section discussing the healing that a particular regression had brought me. For, when I had been regressed to the life of Helen Weaver, it had given me an explanation for my life-long love of Elgar himself as well as of his music, and shown why, at the age of sixteen in my present life, I believed that I would never get over the fact that he had died six years before I was born.

I should like to recount a fascinating story that occurred only last month (July 2016) as a follow-up to one of my books, and from which I am still reeling. When in life one gets a strong prompt to do something, the reasons for it are not always immediately apparent. If, while I was starting to write Life Without Elgar – A Tale of a Journeying Soul, anyone had told me that the book’s main purpose would be to give some healing to the great composer himself, I would certainly not have believed it! While I was enjoying writing that book, the most interesting thing for me about it was how the middle section—consisting of imaginary correspondence between Sir Edward Elgar and his first love, Helen Weaver—wrote itself. The letters had started coming into my head, completely unexpectedly, immediately upon my return from a meeting held in the room that had been Elgar’s own study when he lived at Plas Gwyn, Hereford, between 1904 and 1911. I then continued ‘channelling’ them over the next week or so and, since I was travelling at the time and do not own a laptop, that entailed scribbling in longhand on both trains and aeroplanes. Only after feeling the correspondence to be complete did I write the introduction to the book and then complete the sandwich with an autobiographical first section and a third section discussing the healing that a particular regression had brought me. For, when I had been regressed to the life of Helen Weaver, it had given me an explanation for my life-long love of Elgar himself as well as of his music, and shown why, at the age of sixteen in my present life, I believed that I would never get over the fact that he had died six years before I was born.

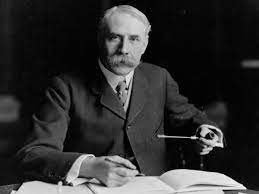

For the benefit of those who are not familiar with the details of this composer’s life, Sir Edward Elgar was born into a fairly humble, Catholic background, his father being a piano tuner who also ran a music shop in Worcester, and—like his predecessor the great Johann Sebastian Bach—he was musically entirely self-taught. He fell in love at a fairly early age with the daughter of a neighbour who ran a shoe shop. Helen was also musical and, like Edward himself, had the violin as her main instrument. Her parents were slightly better off than his and she was consequently able to go to Leipzig to study at the Conservatoire, while he was left behind in England struggling to support himself by teaching music. He did, however, manage one holiday in Leipzig while Helen was there, and they got engaged while enjoying concerts together in the Gewandhaus.

She, however, having already lost her mother at an early age, returned to England when her stepmother became seriously ill and nursed her until her death. Helen was by this time probably suffering from consumption (TB), and she broke off the engagement before emigrating to New Zealand (where she later married and had two children).

There has been much speculation as to the identity firstly of the character who is the subject of Variation No. 13 of the Enigma Variations (Elgar’s best known work apart from the Pomp and Circumstance Marches), and secondly of the “soul who is enshrined” in his violin concerto. But many musicologists have over the years expressed the opinion that both were Helen Weaver, whom they believed Sir Edward never really got over losing.

He later married his piano pupil Alice Roberts, nine years his senior, who came from a wealthy Gloucestershire family, and they strongly disapproved of the match. The couple had one daughter, whom they called Carice, a name derived (typically of Elgar!) from her mother’s names of Caroline Alice. Most of the rest of this great man’s life was a constant struggle financially and to gain recognition as a composer. Alice’s massive role in the latter is indisputably acknowledged and, when she died of cancer in 1920, he severely curtailed composing. His grief was compounded partly by feelings of guilt about certain other romantic attachments that he had had—notably a Platonic relationship with Alice Stuart Wortley, the wife of a Conservative MP and the muse whom henicknamed Windflower.

Towards the very end of his life, however, Elgar had another Platonic relationship with a young divorcee named Vera Hockman, a violinist whom he met while conducting his great oratorio The Dream of Gerontius. She is believed to have inspired the new burst of creativity of his final two years and, when I read Kevin Allen’s book, Elgar in Love, I was convinced that Vera was his twin soul. Despite the prevailing prejudice against both Roman Catholics and the lower classes—not to mention his lack of any formal post-secondary school education—Edward Elgar achieved every possible honour, including knighthood. He was given a Chair at Birmingham University and the title of Master of the King’s Music. He is now known worldwide as one of Britain’s very finest composers.

Thirty-four years after Elgar’s death in 1934, a boy was born in Portugal whose parents named Manuel Eduardo. His family still call him Manuel, but—for some reason he never quite fathomed—he was always known as Eduardo at school. From early childhood he had a great love of music and, though he never took music lessons, he found that he was able to teach himself to play any instrument that he laid his hands on. Yet, feeling sure that he was not destined for a musical career, he completed a degree in mechanical engineering and then became a university teacher in that subject. Manuel Eduardo first met his wife Rosa Maria while he was still at school, and from the very beginning had a constant fear of losing her. They had two sons, but after twenty happy years of marriage, she sadly died of cancer in 2013, at the age of only forty-eight.

Without being aware of who had composed it, Eduardo had always loved the tune of Land of Hope and Glory, and he made a recording of the last night of the Promenade concerts that take place every summer in the Royal Albert Hall, London, in 2004. A random event in July 2015 caused him suddenly to discover that the composer of this work was Elgar—a name he had always felt attracted to, even before knowing who he was. He then started to explore Elgar’s music seriously, falling instantly in love with, for instance, the Enigma Variations and The Dream of Gerontius, and his internet searches soon led him to the great music critic and biographer Michael Kennedy’s Portrait of Elgar and, also, to my little book.

Eduardo then got in touch with me, and we corresponded for about a year—until he came last month firstly to Ludlow to meet me, and secondly to the Three Choirs Festival, which this year was held in Gloucester. By this time the lovely Carla, about whom he had already written to me, saying he was certain that she was his twin soul, had just become his partner, and the couple flew to England accompanied by Eduardo’s two sons and by Carla’s son, a slightly older teenager. From Ludlow they travelled to Gloucester for the first night of the festival and a performance of Elgar’s oratorio, The Kingdom, and the next day they went to Worcester in order to explore some of the main Elgar haunts.

Visiting the Birthplace Museum (at Lower Broadheath just a couple of miles from Worcester city) and walking on the Malvern Hills (which inspired so much of Elgar’s music) moved Eduardo beyond words. Carla was totally overcome by emotion when at the birthplace she saw a portrait of Elgar for the first time and gazed into his eyes. They returned to Gloucester three days after our arrival there—in time for the performance of the Enigma Variations.

Even before meeting this delightful new family, our correspondence had left me pretty convinced of Eduardo’s claim that he was a reincarnation of Edward Elgar, and staying in Gloucester at the same time gave us the opportunity to do a regression to that lifetime. Before we did the regression, Eduardo had told me that when reading about Elgar’s life and personality he had found great resonance with his own, and various other congruencies. For instance, when he read the letters in my book, he knew in the depths of his being that everything recounted therein had really happened; that as Elgar he had never got over Helen’s departure and her not telling him herself that she was going to New Zealand had caused him immense pain. Also that he had coped so badly with Alice’s death that he realised he had had to come back and have the same thing happen again. For he had already identified his wife Rosa Maria as the same soul as Alice Elgar, and clairvoyants in Portugal have also confirmed his sense that his beloved Rosa/Alice is now his main spirit guide.

Performing this regression left me one hundred percent convinced that the former Edward Elgar had now, at last, met his beloved Helen Weaver again. The experience was for me both unprecedented and fascinating, since I had to be the therapist, but also a major participant in the subject’s story. Carla’s presence, however, proved invaluable as she was able to give him some physical consolation while I sat back uttering with conviction the words that he was still needing to hear. For so often do we carry pain through from one lifetime to another, that Edward Elgar, now Eduardo, badly wanted Helen’s assurance that she had always loved him, in spite of not feeling herself to be the right wife for him in that lifetime.

Almost as soon as we met, Carla and I were joking about the curious fact that the former Elgar was now in the same room as both his first and his last love, commenting that we ought to be jealous of one another! However, firstly, I am at present old enough to be Eduardo’s mother and anyway have someone else in my life, and secondly—just as I had felt an immediate soul connection with Eduardo himself—so too did I with Carla. This could not be from the same lifetime, since Vera was not even born before Helen went off to New Zealand, but an inner voice told me that we had previously been sisters, and I now feel that that was in an earlier, South American lifetime. Elgar was renowned for his fascination with gadgets and so—since we tend to do different things in each of our many lifetimes, albeit with certain recurring themes and characteristics—becoming a mechanical engineer on another occasion would make perfect sense. Besides having recognised his new partner Carla as a reincarnation of Vera Hockman, Eduardo has also identified a young friend of whom he is very fond as his previous daughter Carice, and his own younger son as Elgar’s brother who was considered to be the most musically gifted member of the family but who tragically died young. And many of Eduardo’s realisations have been corroborated by clairvoyants in Portugal.

One might wonder whether, believing myself to be Helen Weaver reincarnated, I should not now feel guilty about the pain that she caused her beloved by breaking off the engagement and then disappearing. The simple answer is that I believe in life plans, and I know that, without the suffering that Elgar underwent, some of the world’s most beautiful music could never have flowed from his pen. (The wonderful fifth movement of Brahms’ great German Requiem was written just after his mother had died.)

So, for me, this is a very touching story and, were Eduardo the only person ever to read my book (which is of course not the case—I have received numerous very favourable comments about it), writing it would now be proved to have been incredibly worthwhile. Nor is the story by any means over; for one thing Eduardo plans to return to England next year for the Three Choirs Festival in Worcester (where I intend for us to sit together in the cathedral for the performance of The Dream of Gerontius—a thing that Helen would so dearly have loved to have been able to do!); for another he and Carla have kindly invited David and me to visit them in Portugal (where he says that his house, which he designed himself, bears a remarkable resemblance to the photo in my book of Plas Gwyn, the Elgar family’s Hereford residence!). Since returning home, Eduardo has emailed me saying “You should be happy because you and your book have helped me to overcome the great pain that I was carrying inside me. And I feel that I am becoming prepared for something great in my life— something for the world!”

Here are a couple of the photographs that were taken in the grounds of Gloucester cathedral, following the Elgar Society’s annual lunch, which Eduardo and his family attended with my husband and me. EE, who so greatly loved walking in nature, used to say “The trees are singing my music. Or have I sung theirs?”

Here are a couple of the photographs that were taken in the grounds of Gloucester cathedral, following the Elgar Society’s annual lunch, which Eduardo and his family attended with my husband and me. EE, who so greatly loved walking in nature, used to say “The trees are singing my music. Or have I sung theirs?”

Ann Merivale’s book, Life Without Elgar—A Tale of a Journeying Soul, is published by 6th Books, John Hunt Publishing, at £9.99, and can easily be

purchased either direct from the publisher or from Amazon.