by Gunjan Y. Trivedi and Riri Trivedi

by Gunjan Y. Trivedi and Riri Trivedi

Abstract—The methodology includes measurements, each with their own benefits and limitations, across different levels: physiology, energy, emotions and the mind. Examples illustrate the use of the methodology in depression, loss of loved ones, anxiety, extreme anger, bodily pain, and extreme phobia. Each type of measurement is presented with guidelines to apply it in practical work. Additionally, the future implications of such an approach are explained.

1 Introduction

Regression Therapy often involves working with the challenges faced in the mind and the body which may have an associated emotional and energetic linkage to either current life or past life experiences. Whilst the methodology varies, common themes involve identifying the root cause of the present unwanted experience to a conscious or unconscious memory, related to the past. Common problems by subjects who seek help from regression therapists include relationship issues, anxiety/phobia, social challenges such as lack of confidence, unexplained body symptoms (e.g. migraine), addictions, sexual problems, depression, eating disorders and so on (Tasso Website, 2019). In general, these presenting problems either have a link with painful or traumatic events in a current life or a past life. Past life regression research confirms that individuals are able to relate their experience in trance with a historical challenge in either their current life, or a former life, and are able to find a meaningful answer or create a structure of meaning (Ahluwalia, 2012).

Based on the brief description above, it is clear that Regression Therapy focuses on the emotions, energy associated with the specific incident(s) and how it impacts upon the physical body – including actions and the results. Given the subtle nature of energy and emotions stored in the mind, sceptics often argue this to be a challenging task and given the highly individualized nature of the work involved in Regression Therapy, it becomes more difficult to apply a standard set of tools. Case studies provide useful perspectives on this subject and may also help the regression therapist to learn quickly. However, modern medicine and research in general require a more scientific approach involving statistical analysis. There is a need to initiate the process to establish a common set of standards to measure the emotions, energy and the overall psychological state of the subject in Regression Therapy.

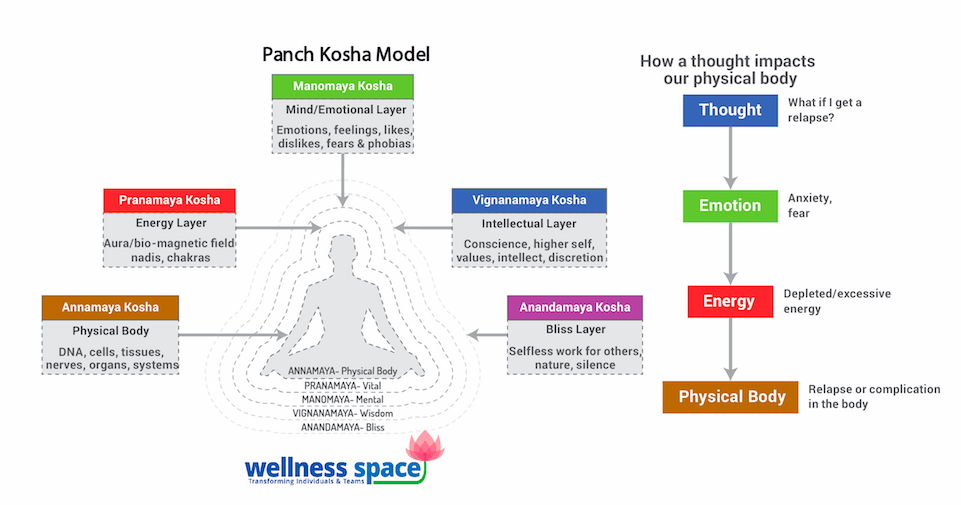

The ancient Indian perspective described as Pancha Kosha provides a powerful framework to understand the work in Regression Therapy (Figure 1). The Pancha Kosha shows the 5 layers of human existence – which are all interconnected – starting from the physical body layer (Annamaya kosha), followed by the energy body (Pranamaya kosha), the daily mind and emotions layer (Manomaya kosha), the higher mind layer (Vijnanamaya kosha) and the bliss layer (Anandmaya kosha) (Satpathy, 2018). These sheaths or layers are all linked to each other. Disruptions in the daily mind (which carries all the emotions) affects the energy sheath causing imbalance in the energy field which in turn affects the physical body. The impact on the physical body results in physiological health issues—which are termed ‘psychosomatic’. The mind/emotions layer contains the imprints of the current life and past life experiences—and repeated traumatic or painful events cause this sheath to be dis-harmonious. In Regression Therapy, the therapist facilitates the understanding of the events from the past that have caused this disruption. Therefore, assisting the client to interpret it through the mind or wisdom from a different perspective. This helps to release the blockage in the energy sheath caused by these past events, and thereby enabling healing in the body. The common theme leveraged by the authors for this is “Release from the body, Reframe in the mind”.

It is important for all regression therapists to define the problem pertaining to the subtle mind and wisdom sheath with specific standards of assessment, in combination with a review of progress versus the base intake data. Many standardized tools (for simplicity, referred to as psychological measurement) are available. The next section reviews the literature in the area of specific tools which can be used to measure generic (e.g. quality of life, and/or wellbeing) and specific (e.g. anxiety, depression, and/or phobia) psychological states.

2 Defining Client Centric Measures of Quality of Life and Well-being

The work in this area relates to the overall quality of life (QoL) of the individual. QoL is often used interchangeably with well-being. The World Health Organization or WHO defines QoL as individuals’ perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns (WHO, 2018). Additionally, the WHO defines health not just as the absence of disease but also a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being (WHO, 2020).

For regression therapists, it is important to understand that the concept of QoL is a broader concept which includes individuals’ perception about their own life and wellbeing in a variety of human life dimensions. This includes realms such as physical, emotional, and social/key relationships etc. (Pinto, 2016). For perspective, there are similar developments related to the quality of life being applied in the European Union that originated as an alternative to growth as a yard of social and economic progress (Walker, 2004). The focus of this article is on the individual’s objective definition of QoL as defined by several aspects of subjective wellbeing.

3 Challenge

The literature review identified the domain of mind (includes emotions as well as higher understanding) (Figure 1) as the primary focus area of measurement. The other two areas identified were human energy and physiology (or the body parameters) – not included in the scope of this article.

The following questions were formulated with a goal to create a few case studies in each area:

- How to define, measure and demonstrate human wellbeing (with a focus on the mind and wisdom layer) in the context of the presenting problems faced by the regression therapists?

- Is it possible to define one generic and a few specific measures that would help evidence the effectiveness and efficiency of the Regression Therapy(TenDam, 2017)?

- Assuming the answer these two questions is “Yes”, is it possible to develop controlled experiments to demonstrate the effectiveness of Regression Therapy based on this pre-defined hypothesis?

The next section provides the methodology that was deployed and validated to address the above questions based on the principles of (a) simplicity (b) prevalence of use in modern research, and (c) scalability.

4 Proposed Methodology

The methodology is summarized in Table 1 with a brief description and benefits. For simplicity, this document will refer to these measures as “psychological” measures to differentiate from “energy” or “physiological” (i.e. body) measures. Each individual psychological measurement area is discussed in later sections.

| Psychological measurement area | Type of measure | Examples (ease of use) | Outcome, Benefits |

| Overall Wellbeing | Generic | WHO-5 Wellbeing Index

The evidence also confirms this index can be used to screen for depression |

Applicable to each individual, easy to compare before and after data. Quick to administer and demonstrated use across medical, emotional and psychiatric problems. |

| Specific areas of mental or emotional wellbeing | Specific questionnaires (based on established standards) | · MDI for depression

· DSM-5 Specific Phobia questionnaire · GAD scale for anxiety · Insomnia Severity Index for Sleep Disruption or Insomnia |

Applicable on a case-by-case basis

Enables the therapist to define the problem and prioritize.

|

Table 1: Proposed methodology to measure wellbeing and specific emotional challenges

5 Overall Well-being of the Subject

Several QoL questionnaires were explored. However, the WHO-5 wellbeing index stood out based on positive research reviews, and the need for simplicity (only 5 simple, non-invasive questions, no copyright conditions allowing free use for everyone and scalability across the types of presenting problems). For more extensive work the WHO (2019) provides several QoL scales, and for specific health-related challenges there are several measures such as EORTC (2019) for cancer-related quality of life. However, most of them require prior approval, are not simple, and require extensive analysis.

The WHO-5 wellbeing index is a short questionnaire of 5 simple and non-invasive questions to measure the subjective well-being of the subjects. It has been translated into 30 languages, validated as a screening tool for depression and considered to be a valid tool in clinical trials (Topp et al, 2015). It has been leveraged in studies ranging from diabetes (Trivedi, 2019a), emotional challenges, substance abuse, stress, psychology and so on (de Wit et al, 2007). In terms of limitations, the WHO-5 focuses on psychological well-being and does not capture specific details for diagnosis such as the identification of a specific phobia, poor sleep quality, relationship issues, or anxiety. If the goal is to identify specific challenges, the therapist must explore tools designed and validated for a specific diagnosis.

Several case studies based on the WHO-5 wellbeing index are captured below (Name/gender/age may have been changed to mask the client identity):

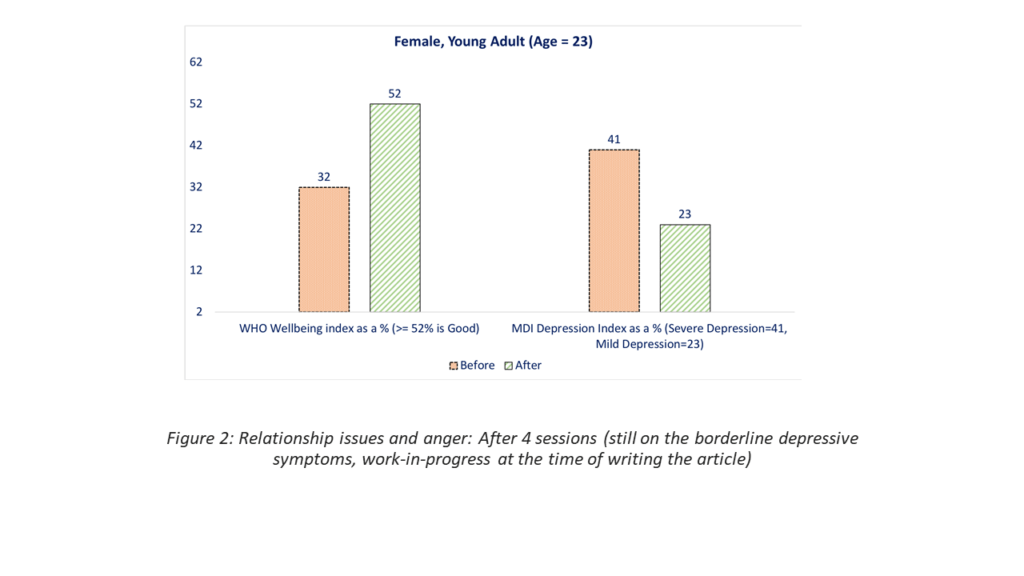

- Relationship issues, anger (Female 23): This subject had relationship issues (multiple concurrent relationships, anger) resulting in poor wellbeing. The root cause was identified as loss of loved ones and the need to fill the void left by the individuals due to sudden loss of a parent in childhood. After 4 sessions, both the scores increased significantly, and this was validated with the client. (Figure 2)

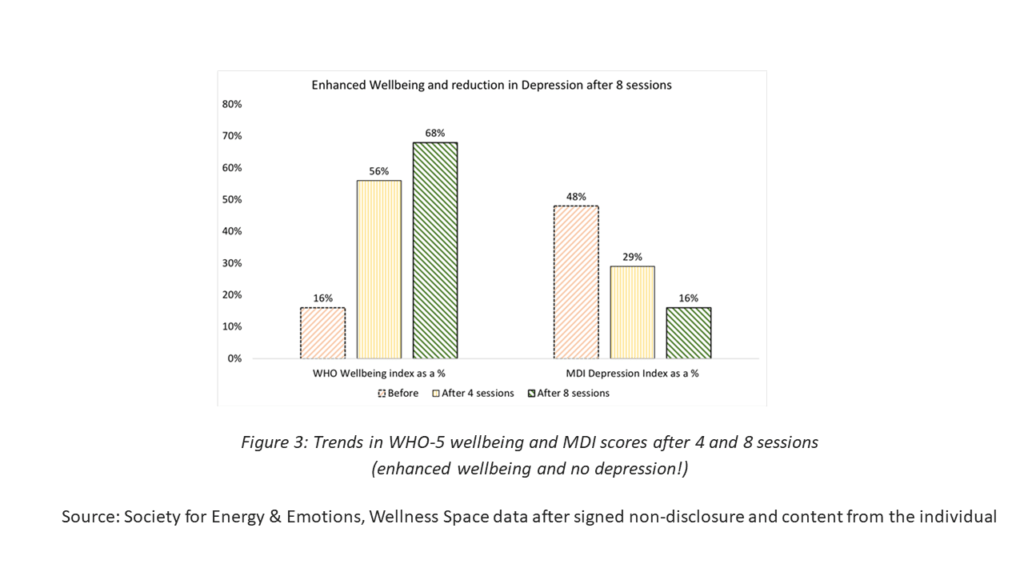

- Depression (Male 43): The subject faced relationship issues based on the pattern (aggressive and demanding father and aggressive and controlling spouse) resulting in alcohol dependence, poor sleep, and stressful life. The WHO-5 score below 52% indicated depressive symptoms and hence specific screening was completed for depression using MDI (Major Depression Inventory) questionnaire – confirming depressive symptoms. Several current life regression and inner child therapy sessions later, the client consistently demonstrated increased confidence, was more balanced – despite similar responses from the spouse and showed a marked increase in wellbeing index (Figure 3).

These examples provide useful insights on how Regression Therapy can influence the understanding of the client about the present situation and provide an enhanced feeling of wellbeing. Before moving to the next session, it would be useful to understand the learnings and watch-outs captured below:

- The WHO-5 wellbeing index is not appropriate to understand the specific problem of the subject (except getting an idea about the possibility of poor wellbeing and depression). To achieve that, a further level of analysis is needed.

- There are subjects who may represent good WHO-5 scores (i.e. good wellbeing). However, they may have a severe challenge that is being intellectualized as “acceptable” and are often just looking to validate their problem versus seeking a solution. This may also happen when the client has a belief system that accepts these conditions as “granted and not modifiable” and is disassociated with the emotions and challenges related to the problem. Such individuals may score according to their belief system and may believe life is such and nothing could be done. This needs to be watched out for and alternative methods need to be probed such as (a) quality of life (b) use of any psychiatric medications (c) major life events and possible correlation with psychosomatic challenges and (d) language used by the client. The scoring is relative – so some clients may downplay their severe condition, and sometimes the clients’ may wish to present a positive and good picture about themselves to the therapist. In both cases the scores can be very misleading, therefore personal interviews/consultation would give a more accurate assessment.

- There are clients who are looking to solve a simple problem for example: I love music and I want to be able to sing but when it comes to going to the stage to sing, I can’t sing. I practice so well and also record my own music while I am learning! Such clients may provide a high score in wellbeing that is consistent with their overall wellbeing and may not see major change in their score even after addressing the issue. This is just a watch-out for the therapist.

- Finally, the therapist may take the simplicity of WHO-5 as “less effective”. This is not true as validated by several research studies leveraging WHO-5, as discussed earlier.

Based on the experience of using the WHO-5 wellbeing index for more than 50 subjects and its reviews across different areas of medical, psychiatric and psychological challenges, this tool can be easily re-applied to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Regression Therapy (as seen by both the subject and the therapist). It is easy to use and can be reapplied across geography, type of presenting problem and for research studies (imagine multiple therapists leveraging this before and after 4-6 sessions to publish a multi-location data of the changes in the wellbeing index after using inner child therapy or past life regression interventions!).

6 Measuring Specific Areas of Emotional or Psychological Challenge

For this study, the focus areas were (a) Depression (b) Specific Phobia (c) Anxiety and (d) Sleep Quality. The shortlisted questionnaires for these measures is captured in Table 2 with references.

| Measure | Methodology | The Rationale |

| Depression | MDI | The MDI is a conservative instrument for diagnosing ICD-10 depression in a clinical setting compared to the M-CIDI interview. Nielsen et. al. (2017) and Konstantinidis et. al. (2011) provide further details. |

| Fear/Phobia | APA-DSM-5 Severity Measure for Specific Phobia -Adult | The American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2020) offers a number of “emerging measures”. These patient assessment measures were developed to be administered at the initial patient interview and to monitor treatment progress. Thus serving to advance the use of initial symptomatic status and patient reported outcome information, as well as the use of “anchored” severity assessment instruments. |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | GAD Scale | The GAD scale is effective in evidencing clinically significant symptoms of anxiety and it can help in differentiating between mild and moderate anxiety in adolescents as per the evidence (Mossman et al., 2017). |

| Sleep Disruption (or Insomnia) | Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) | The Insomnia Severity Index is a very simple and useful tool to understand the extent of sleep disruption. (Morin, 2011) |

Table 2 – Depression, Specific Phobia, Anxiety and Sleep Quality questionnaire and rationale

6.1 Measuring Depression

Depression examples are covered in the earlier section and MDI data just reinforces low WHO-5 scores so in a way it validates the findings. It would be useful to highlight several watch-outs about the use of the MDI form.

- The MDI form is more complex compared to WHO-5 and may require patience for both the therapist and the subject. About 20% of clients usually just tick mark if they are not prompted and guided before filling up each form. Hence it is best to administer this form in person (vs offline).

- The scores vary – as always – from person to person and hence comparing the scores of different individuals (or the scores of the same person before and after a few sessions) can be tricky. Use judgment and experience to identify a broad trend as compared to tracking specific numbers.

6.2 Measurement of Specific Phobia/Fear

The second specific problem we worked with was phobia or extreme fear. This questionnaire was extremely powerful and insightful and provided a very useful process to validate the effectiveness of the intervention. Specific examples (successful and not so successful) are captured below:

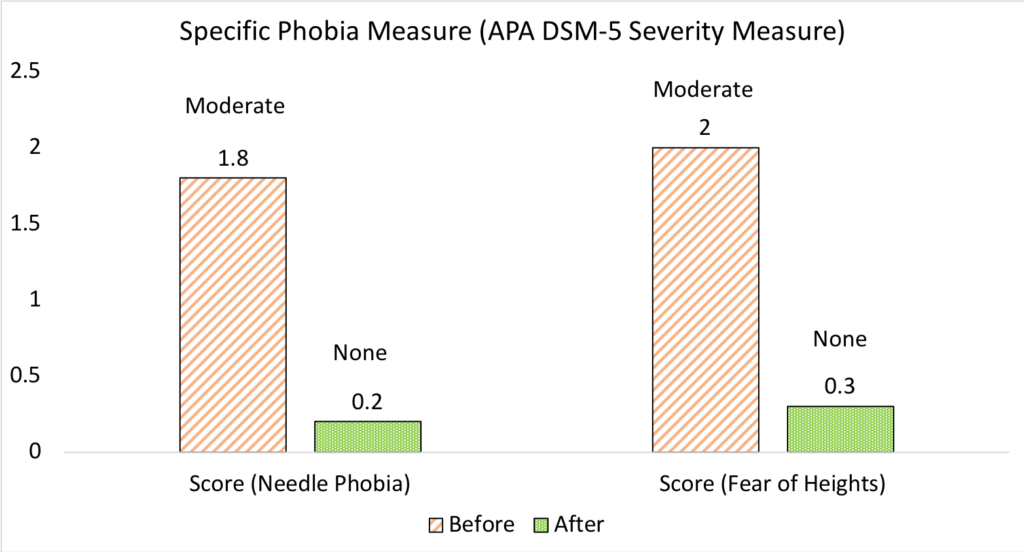

- Extreme phobia of heights and needles (Female 22): Both the fears were of “moderate level” as per the APA DSM-5 Specific Phobia Questionnaire. Unlike many other successful cases, this individual was very keen and insisted on doing as many sessions as needed. In two sessions (one for each phobia), the problem was addressed, and the phobia level went down to “none” in both cases (Figure 4).

- Fear of darkness (Female 21): Fear of darkness is a very common scenario and this person came to one session, felt there was progress and promised but did not follow-up for the second session. Later, upon inquiry, a secondary gain was found in that the person acknowledged she had sought the therapy on the insistence of parents and not of her own accord. Six months later, the phobia was gone. However, the follow-up session was not done and hence the questionnaire was not repeated. This is something to watch-out for when using such an approach, given that the client may not be interested in getting rid of the phobia due to a secondary gain arising from it, or may not take the additional step to follow-up even when the phobia level has become acceptably low and manageable.

Figure 4: APA DSM-5 Severity Measure for Specific Phobia

Source: Society for Energy & Emotions, Wellness Space data after signed non-disclosure and content from the individual

6.3 Measuring Generalized Anxiety

Firstly, it is important to recognize that anxiety has many different categories ranging from Generalized Anxiety disorder (GAD), PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), Social Anxiety Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and so on. For this article, the focus is on understanding Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and exploring a measure to understand how the Regression Therapy intervention can be validated with the improvement in GAD Score. Specific examples of using GAD measurements are captured below:

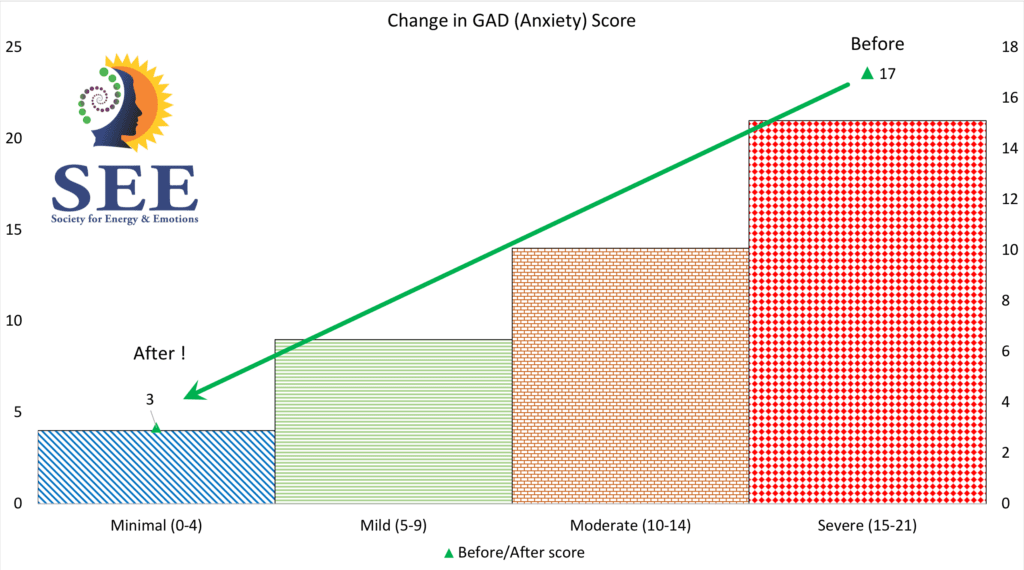

- A woman in her 40s had adverse childhood experiences and had “Severe” anxiety as defined by the GAD score. Her interventions included “acceptance” and release of “negative emotions” attached to those childhood memories – which eventually reduced her anxiety to “Minimal”. It is important to add here that she attended 2 days of Regression Therapy training and also practiced a protocol to reduce stress and enhance focus. The readings were taken about 4 weeks apart. (Figure 5)

- There are cases where the GAD measure may not be “perfect” however it does provide an indication. For example, in the case of an individual who had childhood physical trauma (one of the parents had subjected the child to emotional and physical abuse) the GAD score reduced, and despite previously being hospitalized for panic attacks, in 5 weeks his score went down to “Mild”. This case is a work-in-progress at the time of writing this article. However, the GAD was consistent with how the individual felt and provided a reasonable benchmark. Needless to add, the data from such forms must be interpreted with caution and needs to be supplemented with face to face meetings and understanding of how the subject felt (versus just depending on the forms).

Figure 5: GAD measurement after 5 sessions (the bars show Anxiety levels as defined by GAD)

6.4 Measuring Sleep Quality

From the Regression Therapy perspective, it is important to assess the quality of sleep and also identify if the interventions are helping in improving the quality of sleep. The evidence provided by Pace-Schott et. al. (2015) confirms that disrupted sleep may impair emotional recovery during the critical period following traumatic stress and that improved quality of sleep can help in such cases.

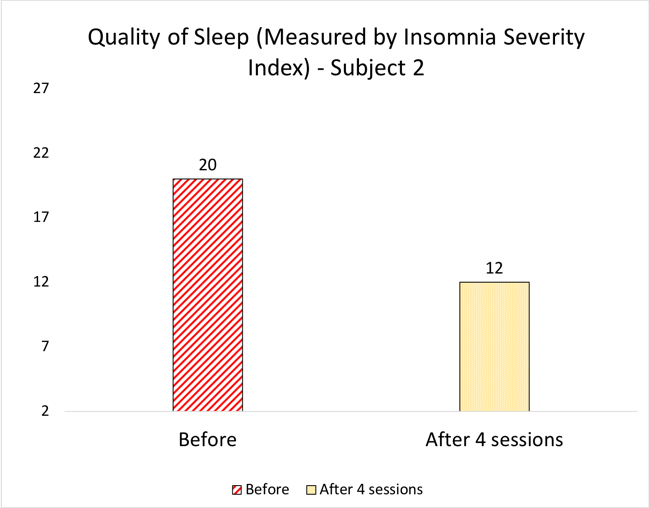

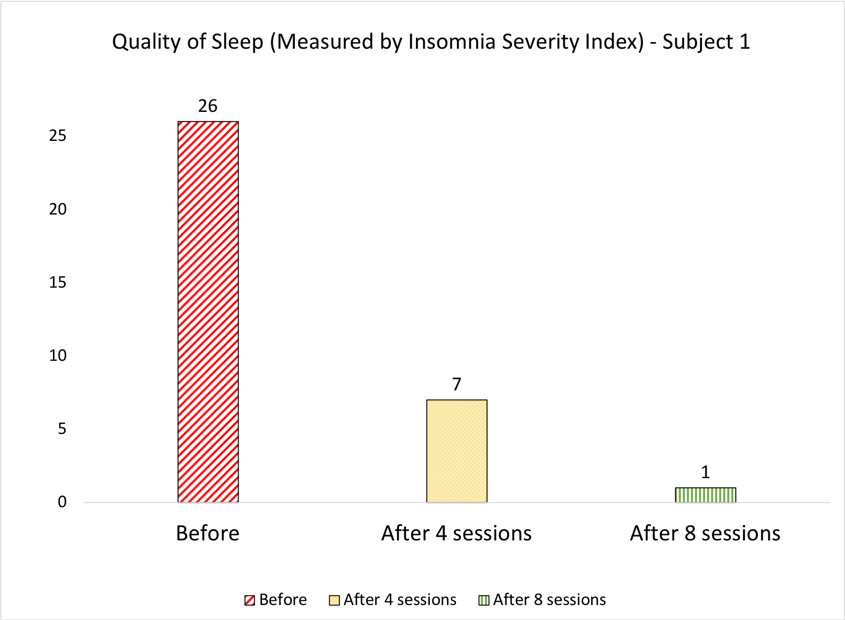

Improved sleep is essential for a better quality of life and emotional regulation. There are multiple objective and subjective assessments for sleep quality and an article by Trivedi (2019b) proposes a simple questionnaire (Insomnia Severity Index). Two examples shown in Figure 6 provide useful insights on how this questionnaire can help.

- Subject 1 had severe Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) based on adverse childhood experiences, had very poor quality of sleep and needed longer interventions. This individual also complained of nightmares (which reduced mid-way through the interventions and eventually were gone post 8 sessions).

- Subject 2 also had adverse childhood experiences (emotional, physical abuse) however, the presenting problem was sleep disruption (despite strong medications). The work, for this individual, focused around regression to specific events and somatic release of the emotional charge. Despite doing minimal work on sleep quality, the outcome shows a significant enhancement in sleep just after 4 sessions.

Sleep quality is a very important area and specific elements of sleep (e.g. REM or Rapid Eye Movement) have strong correlations with emotional regulation. This document is focused on identifying tools to measure sleep quality. With the advent of technology, more objective tools (e.g. a good quality wristwatch or Actigraphy) are likely to be available. The recommended approach is just a simple subjective assessment tool that is known to be useful for initial screening and assessment. The limitations of any subjective assessment also apply to ISI and if an objective assessment is not possible (e.g. due to cost or availability) alternative subjective assessments should be explored (Trivedi, 2019b).

Figure 6 : Quality of Sleep Measurement: Data for 2 subjects showing the trends measured after 4 and 8 sessions respectively.

The above examples provide a confirmation that it is possible to devise a methodology to articulate the state of the human mind and wellbeing as presented to the regression therapist. Based on the outcome of the generic WHO-5 Wellbeing assessment tool, the therapist can pursue a specific questionnaire (e.g. phobia) and validate the initial challenges faced by the therapist. If there are multiple presenting problems, the specific questions can help the therapist define the most important problem – which enhances the effectiveness of the work and speeds up the progress (efficiency!). Let’s consider how data can be scaled up as part of a controlled experiment.

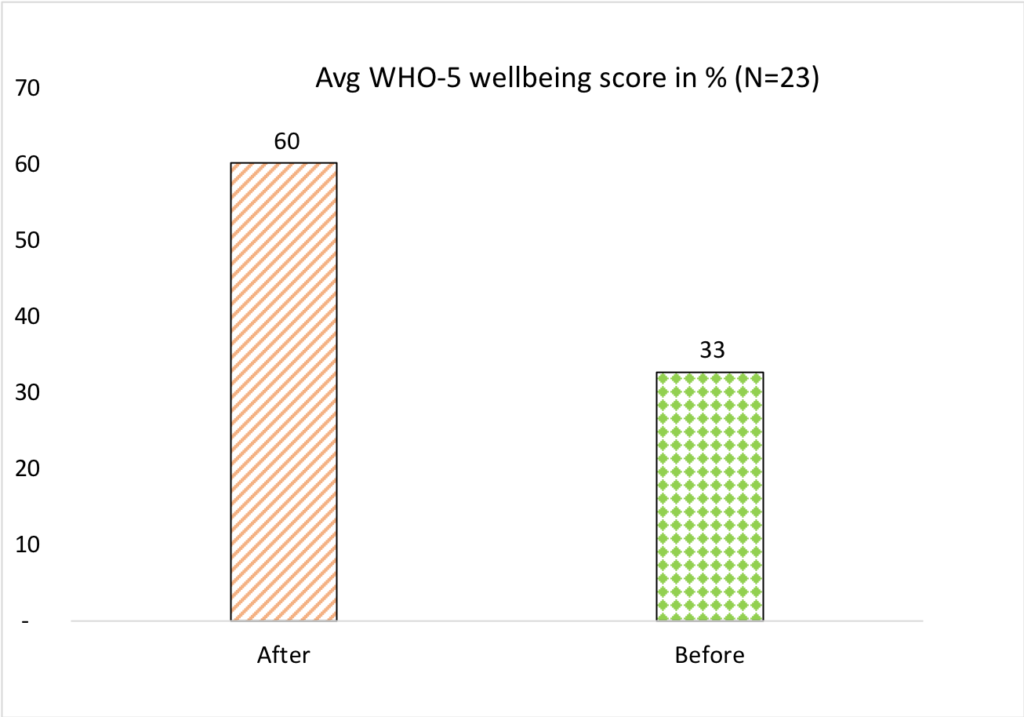

7 Scaling up the data for a research study

The graph in Figure 7 shows the WHO-5 Wellbeing Index Data of 23 subjects before and after the intervention. Based on the average increase, it is evident that the interventions are working and as the number of samples increases, it is possible to analyze this data by intervention type, therapist, number of sessions, and those with or without psychiatric medications and so on to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the work. Such data can be shared broadly as well as with the medical community to create more visibility of the work. The scope needs to be extended to include a “control” group who did not go through any Regression Therapy, to make it more meaningful.

Figure 7 – WHO (Zarse, 2019)-5 Wellbeing Index score before and after (4 Regression Therapy interventions)

(Source: Society for Energy & Emotions, Wellness Space data after signed non-disclosure and content from the individuals)

8 Therapy Watch-outs

All the above cases and data represent the individuals’ own interpretation of how he/she feels. This creates a likely presence of personality bias and subjectivity. As a result, the surveys only provide a framework that is commonly accepted in psychology and medicine – including psychiatry. The regression therapist must use her/his judgment in interpreting the data and accordingly seek to understand the basis of the score via the client interview to validate if there are any gaps in the score as compared to the client’s state.

Another important factor often not considered by therapists focusing only on “qualitative assessment” is the extent of adverse childhood experiences faced by the subject. Nearly two decades of research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (based on the ACE-Q questionnaire) has identified a significant correlation between (a) detrimental childhood experiences and (b) their secondary effects on brain development and parenting behavior as key root causes of overall disease burden and mortality in the general population (Zarse et al, 2019). The evidence points to the increased risk of not only psychiatric disorders but also addictions and medical illnesses (multi-organ) in adulthood based on adverse childhood experiences. This work needs to be considered in future measurement methodologies since a higher ACE score is likely to have a much deeper impact on intensity, frequency and methodologies used by egression therapists. The extent of PTSD may also become a significant factor in therapeutic intervention planning (not included in the scope of this document).

9 Discussion

The proposed methodologies in Table 1 and 2 provide a framework that is (a) Simple – since all the surveys have very few questions and are constructed in basic English (b) Prevalent in psychology and medicine – since the selected instruments are commonly used in medical and psychological research and (c) Scalable – especially since some of the processes can be used by multiple therapists or wellbeing centers.

The challenges in deploying this intervention are captured below:

- Subjectivity due to the individual’s own perception, personality bias, or at times unwillingness to formally put his/her issues into a measurable form.

- Variations in the score – since some surveys are to be conducted bi-weekly, there is a risk that today’s emotional issue may tend to impact the individual’s wellbeing and that he/she may reflect this in the survey (versus putting scores on the basis of past 2 weeks, as suggested in WHO-5).

- Self-administered versus therapist guided scores may vary since not all the subjects are fluent in English. The availability of a therapist or a staff member to guide the individual may encourage the subject to ask questions and generate a more accurate response. One common issue encountered, as captured earlier, is – “Unless people read the whole form, they tend to reflect today’s perspective in the form even if the survey has clearly mentioned that the past 2 weeks’ perspective must be captured”.

- Choosing the appropriate form could also be a challenge. For example, using a GAD form for phobia (and vice versa) is not recommended and could mislead the subject and the therapist.

Despite the above challenges, due to the obvious simplicity, prevalence and scalability, the approach explored above provides a promising template for regression therapists in terms of increasing the evidentiary effectiveness and hence the credibility of their work. Presenting the outcome of therapeutic interventions using globally accepted measures could enable the therapists to understand and articulate which areas Regression Therapy could be more powerful within and can also highlight default areas where such therapy alone may not be sufficient whereby the subject may require psychiatric interventions along with Regression Therapy. Future work in this area could consider physiology and energy-specific measurements and also incorporate adverse childhood experience and PTSD related measures.

9 Conclusion

The case studies and examples evidencing using Regression Therapy alongside psychological measurements indicate a wide realm of potential for re-application by the Regression Therapy community. As previously noted, this is due to (a) Simplicity (b) Prevalence and (c) Scalability. The proposed methodology provides a useful framework for fellow therapists to explore and also to articulate the benefits of the interventions to the audience (including medical professionals and psychologists as well as common people). More work in this area is bound to provide a strong framework to understand the areas where Regression Therapy could be more effective or efficient – thereby potentially creating more demand and also buy-in from individuals who need help as well as psychiatrists and psychologists. Additional work such as more samples and possibly the addition of a control group is needed to validate this methodology for Regression Therapy and also create a strong framework of research related to wellbeing, depression, anxiety, phobia and so on.

Acknowledgements:

Gunjan Y Trivedi would like to acknowledge the discussions and inputs from Dr. Hans TenDam starting with initial discussions at the World Congress for Regression Therapy in 2017 and follow-up suggestions which has led to this research document.

REFERENCES

Ahluwalia, H. (2012). Subjective experience of past life regression. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science,2(6), 39-45. doi:10.9790/0837-0263945

APA. (2020). Online assessment measures. Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/educational-resources/assessment-measures

de Wit, M., Pouwer, F., Gemke, R. J., Delemarre-van de Waal, H.A., & Snoek, F. J. (2007). Validation of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 30(8): 2003-2006. doi:10.2337/dc07-0447

EORTC. (2019). European organization for research and treatment of cancer. https://www.eortc.org/

Konstantinidis, A., Martiny, K., Bech, P., & Kasper, S. (2011). A comparison of the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) in severely depressed patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2011;15(1):56-61. doi:10.3109/13651501.2010.507870

Morin, C. M. (2011). The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. doi:10.1093/sleep/34.5.601, 601–608.

Mossman, S.A., Luft, M.J., Schroeder, H.K., Varney, S.T., Fleck, D.E., Barzman, D.H., Gilman, R., DelBello, M.P., & Strawn, J.R. (2017). The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder: Signal detection and validation. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 29(4): pp.227-234. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29069107/

Nielsen, M. G., Ørnbøl, E., Bech, P., Vestergaard, M., & Christensen, K. S. (2017). The criterion validity of the web-based Major Depression Inventory when used on clinical suspicion of depression in primary care. Clinical Epidemiology, 9, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S132913

Pace-Schott, E. F., Germain, A., & Milad, M. R. (2015). Sleep and REM sleep disturbance in the pathophysiology of PTSD: The role of extinction memory. Biology of Mood & Anxiety disorders, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13587-015-0018-9

Phobia—Adult, S. M. (2020, March 9). Retrieved from American Psychiatric Association: http://www.dsm5.org/Pages/Feedback-Form.aspx

Pinto, S. F. (2016). Comfort, well-being and quality of life: Discussion of the differences and similarities among the concepts. Porto Biomedical Journal, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbj.2016.11.003.

Satpathy, B. (2018). Pancha Kosha Theory of Personality. The International Journal of Indian Psychology. DOI: 10.25215/0602.105.

Tasso (2019). Tasso International Website.https://tassointernational.com/regression-therapy-problems/

TenDam, H. (2017). Toward a esearch agenda for regression herapy. The International Journal of Regression Therapy. Vol, 25, pp. 65-68.

Topp, C.W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 Wellbeing Index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1159/000376585

Trivedi, G. Y. (2019a). Importance of Screening for Wellbeing in Diabetes Management. Current Research in Diabetes & Obesity Journal, Vol.11, Issue 4. https://juniperpublishers.com/crdoj/pdf/CRDOJ.MS.ID.555820.pdf

Trivedi, G. Y. (2019b). Importance of screening for Sleep Disorders (Chronic disease). Journal of Clinical Diabetology, Vol 5,Issue 3.

Walker A., v. d. (2004). Challenges for Quality of Life in the Contemporary World. Challenges for Quality of Life in the Contemporary World. Social Indicators Research Series, 24.

WHO (2018). Retrieved from Measurement of QOL -: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/sage/SAGE_Meeting_Dec2012_PowerM.pdf

WHO (2019) World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whoqol-qualityoflife/en/index1.html

WHO (2020). Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/

Zarse, E.M., Neff, M.R., Yoder, R., Hulvershorn, L., Chambers, J.E., Chambers, R.A. (2019). The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Medicine, 6:1. DOI: 10.1080/2331205X.2019.1581447