by Paul W. Schenk, Psy.D.

Abstract

Abstract

The author presents a layered genogram model for conceptualizing and utilizing hypnotic phenomena of the “past-life” type. An earlier article (Schenk, 1999) discussed a different model which bypasses the question of reincarnation by interpreting the client’s “waking dream” as a purely metaphorical projection from the unconscious. The model presented here incorporates reincarnation concepts by adding a fourth dimension to family/systems models of psychotherapy. The article then applies the model to several case studies to demonstrate some of its clinical applications. Whether the hypnotic imagery is understood as factual or symbolic, a growing body of literature indicates that treatment strategies associated with past-life therapy are often effective in treating Axis I symptoms which have not responded to other treatment approaches. These techniques can also bring about, albeit more slowly, durable Axis II personality changes similar to those seen as sequella of near-death experiences.

Psychotherapists risk professional ostracism from their colleagues when they work in an area that is perceived by many as lacking scientific credibility. This creates a classic double bind: Scientific credibility can only be established by those who are willing to risk their own credibility by doing research in areas where credibility has not yet been established. For the clinician doing research in past-life therapy, however, this double bind is accompanied by an additional obstacle. Past-life therapy presupposes reincarnation is a reality – a possibility that many therapists and lay people believe is impossible because their religious convictions exclude it. The author finds this particularly ironic, as this kind of psychotherapy tends to be intensely spiritual.

Ross (1991) has observed that “a cultural dissociation barrier has been erected that effectively removes from consideration those parts of self that deal with experiences that are unacceptable to Western thinking.” Crabtree (1992) terms this “cultural hypnosis.” He observed that the kinds of experiences which are rejected in this manner fall into three main categories:

- paranormal experiences

- deep intuitive consciousness

- programs responsible for running the physical organism (such as the autonomic nervous system)

Crabtree states, “Because we live in a state of ‘consensus trance’ we are highly suggestible. In this state, we accept as real what our culture has agreed to call real, and we deny the reality of what our culture ignores.” At a cultural level he suggests that this means listening more carefully to the people who have experiences that fall into the three categories of rejected/denied experience. Unlike much of the world’s population, reincarnation still falls outside the religious dissociation barrier of many Americans, both lay and professional (Moody, 1999).

Moody (1975) and Sabom (1982) found that patients who have had a near-death experience (NDE) rarely disclose it to their physician unless specifically asked for fear of how the physician would react. Similarly, psychotherapy clients seldom bring the question of reincarnation into therapy unless the therapist inquires about the client’s beliefs. When they do, however, it is difficult to miss. This is particularly true if imagery of the past-life type occurs spontaneously during hypnosis work (e.g., Weiss, 1988). The experience can be startling for both the clinician and the client. How it is handled can have significant impact on the therapeutic relationship.

The urge to resolve the cognitive dissonance that results from such experiences can provide considerable energy to read, explore, and rethink one’s theories and models. The interested clinician can turn to a variety of books (e.g., Stevenson, 1966, 1977a, 1977b, 1984, 1987, 1997a, 1997b, 2003; Lucas, 1993; Almeder, 1987, 1992; Cardena et. al, 2000; Moody, 1975, 1977, 1991, 1999; Ring, 1980, 1984; Bowman, 1997; Fiore, 1978; Cerminara, 1950; Tucker, 2005; Weiss, 1988, 1992, 1996; Wambach, 1979). The willingness to explore the possible ramifications of reincarnation can be much more difficult to the extent that a belief in reincarnation does not overlap one’s own core religious or spiritual beliefs. The shift from a model of life lived once to a model that includes reincarnation has major consequences. Fortunately, the author’s experience is that these neither need to be fully understood nor resolved in order to make use of the clinical implications.

When conducting research in any area, it is useful to draw on the various kinds of evidence that can establish scientific credibility. Such evidence comes from several sources including:

- Pure research – such as the kind which is done out of basic curiosity, “I wonder what would happen if…”

- Applied research – such as longitudinal and retrospective studies which test theories using a priori or a posteriori

- Incidental discoveries (such as Teflon) made while doing a different task.

- Observed data that does not fit existing theories. One example would be the holographic theory of memory storage that replaced Penfield’s earlier model of localized storage in the brain (Talbot, 1991).

The theoretical model presented here has been derived from a mix of the above sources of information gathered over the past 18 years. The model is a straightforward extension of concepts developed by family/systems therapists such as Haley, Watzlawick, and Minuchin. It incorporates reincarnation concepts by adding an additional dimension to how systems are drawn and conceptualized. The author has previously presented (Schenk, 1999) an alternative model for understanding and utilizing hypnotic phenomena of the past-life type that avoids any reference to the question of reincarnation and past lives. In that model, the hypnotic imagery of the client’s “waking dream” is interpreted as purely metaphorical. The therapist works interactively with the dream content, drawing on the theories and therapeutic strategies of therapists like Freud, Jung, Perls, and Sacerdote (1967) who viewed dream material as a projection from the unconscious.

The author believes that both models provide clear frameworks for conducting clinical research and evaluating the efficacy of these particular approaches for treating specific symptoms. Both models utilize traditional psychotherapy tools such as trauma treatment strategies, paradox, cognitive reframing, corrective emotional experiences, etc. Both models can produce clear symptom reduction (1st order change) and/or existential/spiritual shifts (2nd order change). Indeed, it is the intensely psychospiritual aspect of this work that the author finds the most intriguing and rewarding.

The theory: Family/systems therapy in the fourth dimension

Traditional psychotherapies that use an intrapsychic model can be conceived of as one dimensional: the individual (a point) moving across time (which defines a line) as in Figure 1.

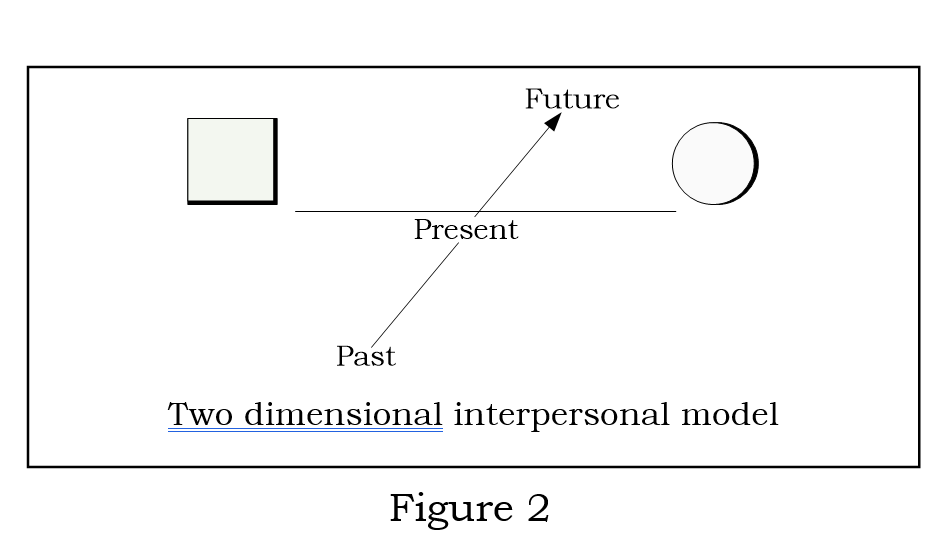

Interpersonal models can be conceived of as two dimensional: the dyad (represented as a line) moving across time (the 2nd dimension) as in Figure 2.

Family/Systems models can be thought of as three dimensional[1]: the genogram (drawn in two dimensions) moving across time as in Figure 3. In each of the three models, the dimension of time makes the model dynamic. At any single moment in time, therapy may focus on an individual in the family system (1-D), a dyad such as a parent–child relationship (2-D), or the larger system (3-D). Note that the fact that a 2-D view may be enough to explain an observed problem does not mean that there is not also a 3-D problem. For example, a couple with co-dependency problems may also have a history involving parents whose relationships with other family members was characterized by similar dynamics.

Family/Systems models can be thought of as three dimensional[1]: the genogram (drawn in two dimensions) moving across time as in Figure 3. In each of the three models, the dimension of time makes the model dynamic. At any single moment in time, therapy may focus on an individual in the family system (1-D), a dyad such as a parent–child relationship (2-D), or the larger system (3-D). Note that the fact that a 2-D view may be enough to explain an observed problem does not mean that there is not also a 3-D problem. For example, a couple with co-dependency problems may also have a history involving parents whose relationships with other family members was characterized by similar dynamics.

Genograms provide the therapist with a simple, visual way of charting people, events, and major themes in a family’s history. For example, the author was having trouble getting a 16 year old client to even allow the possibility that her mother might have reason to be concerned about the girl getting pregnant — until he showed her the genogram he had drawn of her family (Figure 4).

As she looked at the drawing, she made a quantum, durable shift in her attentiveness to her risks of becoming pregnant. She did not need to know the specifics of how her mother and grandmother each became pregnant at exactly the same age. She knew that she, herself, had no intentions of becoming pregnant at 16, and was willing to assume her predecessors had felt the same. She decided that something seemed to make 16 a very risky time for first born women in her family, and became very clear she would not ignore that simple observation.

The clinical use of such three dimensional genograms provides a rich way of organizing and displaying a wealth of information about individuals, couples, and family systems1. The therapist can move back and forth from intrapsychic factors (1-D), to interpersonal factors (2-D), to systemic level factors (3-D) as the needs of a session dictate. The fourth dimension extension to genograms that follows will make more sense with the help of a visual analogy drawn from a classic work written more than 100 years ago.

In the late 19th century, a Shakespearean scholar wrote a social parable titled Flatland: A Parable of Spiritual Dimensions (Abbott, 1884). The allegorical tale is narrated by a square, an inhabitant of a two dimensional world known as Flatland. Social standing in Flatland is determined by the number of sides one has, with circles holding the highest status. As a new millennium arrives, the square is visited by a sphere from Spaceland. The sphere’s ability to seemingly change size (as a function of its intersection with the plane of Flatland), and even to disappear and reappear at will, frightens the square. The sphere struggles at length to explain the concept of the third dimension having initially expected it to be easy: “Just look up,” the sphere had suggested. “But where is up?” asks the square. The sphere tries a mathematical proof of the existence of the third dimension:

Square: And what may be the nature of the Figure which I am to shape out of this motion which you are pleased to denote by the word “upward?” I presume it is indescribable in the language of Flatland.

Sphere: Oh, certainly. But I will describe it to you. We begin with a single Point, which of course – being itself a Point – has only one terminal Point. One Point (moving in a single direction) produces a Line with two terminal Points. One Line produces a Square with four terminal Points (corners). Now you can give yourself the answer to your own question: 1, 2, 4, are evidently in Geometrical Progression. What is the next number?

Square: Eight…And how many solids or sides will appertain to this Being whom I am to generate by the motion of my inside in an “upward” direction, and whom you call a Cube?

Sphere: How can you ask? And you a mathematician! The side of anything is always, if I may say so, one Dimension behind the thing. Consequently, as there is no Dimension behind a Point, a Point has 0 sides; a Line, if I may say, has two sides; a Square has four sides; 0, 2, 4; what Progression do you call that?

Square: Arithmetical.

Sphere: And what is the next number?

Square: Six.

Sphere: Exactly. Then you see you have answered your own question. The Cube, which you will generate, will be bounded by six sides; that is to say, six of your insides. You see it all now, eh?

Square: Monster, be thou juggler, enchanter, dream, or devil, no more will I endure thy mockeries. Either thou or I must perish.

Eventually, the sphere lifts the square out of its world. The square is suddenly able to see every side of other squares simultaneously, where it had never been able to see more than two sides from a two dimensional perspective. Even more shocking to the square, it is able to look inside all the two dimensional objects in its world. The square quickly comprehends the implications of this new perspective. Turning to the sphere it entreats him to show it what the three dimensions of Spaceland look like from the perspective of the fourth dimension. The sphere confidently answers, “There is no such land. The very idea of it is utterly inconceivable.” Note how the sphere’s response is a wonderful example of Crabtree’s concept of “consensus trance.”

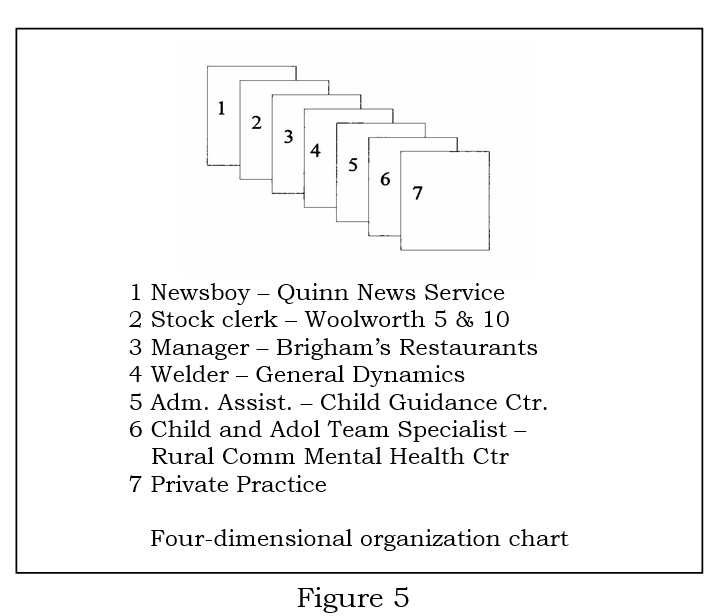

A simple test of the therapeutic utility of four dimensional genograms comes from their parallel form in business – the organizational chart. Just as therapists can draw genograms to visually represent relationships within an extended family, personnel managers can draw organizational charts to visually depict relationships within and among different levels of an organization. At its simplest level is the individual employee, analogous to the intrapsychic model of psychotherapy. Next would be the supervisor-supervisee relationship, analogous to the two dimensional model. A simple three dimensional organizational chart might show the employees within a given department or unit, under the supervision of the department head or manager. Like a fully detailed family tree, the full organizational chart of a company can become quite complex.

When a given employee’s career history is plotted over time as a collection of these organizational charts from each company where the employee has ever worked, additional information about the employee is suddenly available in the four dimensional organizational chart that a single (3-D) chart can never reveal. For example, figure 5 below shows a subsection of the author’s own career path, where each page would contain the genogram of the respective company/organization:

A supervisor who wants to fully understand the current skills, attitudes, and weaknesses of a given employee may find it very useful to take a more detailed history of the experiences that the employee had at each of the other companies where she/he previously worked. The years spent in these other positions may well contain events which still have considerable influence on the employee’s current performance and relationships with peers and supervisors. To draw a parallel from Stevenson’s research (1977) on the explanatory value of reincarnation, one can see how the employment history at earlier companies might help explain factors influencing such things as:

- the employee’s particular career interests

- a strong dislike of certain tasks

- skills which the supervisor didn’t realize the employee possessed

- an unexpectedly difficult relationship with a supervisor or co-worker

- unusually strong feelings about other companies

- factors which explain previous injuries or scars

On the one hand, these may seem quite evident. An employee’s skills and assets are acquired over years of experience. Some aspect of a prior position may have allowed the person to develop skills in grant writing, or troubleshoot computer software problems, or coordinate the efforts of a team working on a project. Often an employee’s liabilities have also been acquired over years of experience. A new typist’s problems with carpal tunnel syndrome may have developed over an extended period of time. A mechanic’s periodic back problems may date back to a single job related injury 10 or 20 years before. A salesperson’s problems with supervisors may stem from “politics” at a former company where the employee was treated unfairly. A job resume by itself is unlikely to contain the information needed to fully “diagnose” the origins of the current problem. But the supervisor can use it as a road map when talking with the employee to help search for the information which is relevant to the current problem.

If time is the first dimension in each of the psychotherapy models presented above, then reincarnation can be thought of as simply extending the three dimensional model of the family genogram one dimension further into the fourth dimension. If each lifetime of the soul is drawn as a separate genogram, lines between these layered genograms represent the path of the individual across lifetimes. (For purposes of this discussion, the reader is asked to indulge the probably inaccurate implication that time is linear). The model easily accommodates the idea of two people who have known each other in other lifetimes; whether as siblings, spouses, parent-child, friends, etc. “Soul mates” can be understood as two people whose genograms include intersection points across a larger number of lifetimes. To the extent that the assumptions underlying the one, two, and three dimensional models of psychotherapy are valid, the same assumptions remain valid as a subset of the four dimensional reincarnation model. For example, if a co-dependent couple (2-D) can validly trace some of the roots of their interpersonal problems to childhoods with alcoholic or abusive parents (3-D), then other problems may sometimes have roots in another dimension — in another lifetime (4-D).

Note that turning to past lives to explain symptoms is not required in this model any more than a therapist must always turn to a multi-generational family genogram to explain a given client’s presenting symptoms. If effective therapy can be done with an intrapsychic or interpersonal model for a given client, there is no need to complicate the formulation of the case. As Freud is said to have reminded the student who questioned him about his cigar being a phallic symbol, “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.”

Two major tests of any model or theory lie in its ability to explain past events (a posteriori) and to predict future events (a priori). It is one thing for two events to correlate in some way. It is an entirely different matter to state that one event caused another. It is this distinction which is often the basis for a clinician’s rejection of past-life imagery. It is one thing to say that a client who is involved in say, a co-dependent relationship, conjures up a hypnotically facilitated waking dream of another lifetime in which the client was similarly enmeshed with the same person. As a projective technique, there would be little argument that the client could simply have “dreamed up” a story which highly correlates with the current reality. The critic correctly argues that reincarnation is not needed to explain the dream imagery. The fallacy of the argument begins at this point, however, if the critic implicitly assumes that correlation precludes causation (from another lifetime). In this situation, the critic is implicitly arguing that because the two can be explained with current life information (a two or three dimensional model), the two cannot ever also be explained as true from a four dimensional model involving past-life roots. It is like the sphere in Flatland trying to convince the square that because three dimensions are enough to explain the square’s experience of the sphere (as able to change diameter or even totally disappear at will) a fourth dimension cannot exist.

Both theoretical models (i.e., in the author’s 1999 article and in this one) assume that something outside the client’s conscious awareness is selecting material which is relative to the presenting problem(s). The model presented here assumes the selected material is factual; the model in the 1999 article assumes it is metaphorical/symbolic. In clinical practice, the author finds the effectiveness of these techniques in treating a variety of Axis I and Axis II symptoms appears to be independent of both the client’s and therapist’s views about reincarnation. From a pragmatic standpoint during the therapy session, it doesn’t matter whether the imagery is interpreted as factual or metaphorical. The therapist only needs to change the induction slightly to shift from one model to the other, or to include both as possibilities:

If ideomotor signaling (Rossi & Cheek, 1988; Rossi, 1986) has indicated there is a past-life connection to the current problem, the therapist might continue by suggesting that your higher self can move you at the speed of thought across time and space to a lifetime which contains important information about (the symptom)…

If the hypnosis work is approached as a waking dream, the therapist can include language such as I’d like to invite your unconscious to work with us today in presenting to you a dream, a symbolic story, whose content will address (the presenting problem) in a way that is timely, useful, and constructive…

For the client who is comfortable with both models, the language can be more inclusive: …so that with regards to (the presenting problem), your higher self can bring into consciousness timely, useful, constructive imagery and content that you may understand as coming from another life or as symbolically relevant to your current situation…

In the same way that therapists working with a client’s childhood memories carefully seek to remain neutral as to their gist/detail accuracy (Brown and Scheflin, 1998), the therapist working with past-life imagery seeks to remain similarly neutral. The therapeutic usefulness of the hypnotic experiences does not hinge on which model is correct.2 To demonstrate this idea, consider the following anecdote:

The client was a middle aged, white, male physician. In an earlier session he had met a “guide” named Thomas who had a wonderful sense of humor. Through the client I asked “Thomas” if there was a way to tell the difference between real past-life imagery and imagery which is just metaphorical. The client reported the following response from Thomas:

“Yes (pause), but we aren’t going to tell you how to tell the difference (pause), because we don’t want you to get distracted. (Pause) And, by the way, today’s imagery is just imagery.”

The remainder of the session contained a “past-life” type experience that the client reported was just as vivid and just as clinically useful in addressing his presenting issues as had been his previous experiences. Since the client believed in reincarnation when he initially came for therapy, the suggestion is that “Thomas” did not want the client to miss the therapeutic potential of the symbolic imagery by dismissing it as “not real.” Note, however, that if the client’s unconscious created Thomas as well as the imagery, it also did a nice job of staying “meta-” to the question we had posed by reminding him to focus on the relevancy of the imagery about to be presented!

The actual application of both models allows the use of a variety of traditional therapy strategies. Among the more frequent strategies the author employs are the following:

- Braun’s BASK model of memory (1988a, 1988b) is often helpful. When current emotions or behavior do not match the available information (Behavior, Affect, Sensations, Knowledge), the unexpected difference is postulated to be attributable to memories from prior events which are not fully conscious. Classic trauma treatment work involves the re-association of these dissociated memory fragments so that the response makes sense. For example, in past-life work, a presenting symptom such as a fear of drowning often resolves rapidly after accessing a past life in which the person died by drowning. The irrational fear of the phobic situation becomes a rational fear when the “true” origin is recovered and worked through. Again, the client does not need to define the recovered imagery as factual for the symptom to resolve. It seems to function just as well if the content is defined as only symbolic.

- The client’s imagery routinely includes the person’s death in that lifetime or waking dream.3 For the therapist, familiarity with the NDE literature is very helpful here. Clients often report being in a bright light and having the experience of the presence of angels, guides, or dead relatives (from that lifetime). These figures are always experienced as loving, nonjudgmental, and unconditional in their acceptance of the person. For the client whose life has included few experiences of “unconditional positive regard,” the after-death phenomena associated with both models routinely provide powerful emotional experiences. Taken literally, these encounters provide an excellent opportunity to rework decisions made at the time of death, to release physical symptoms that correspond to injuries sustained during a traumatic death, and to forgive self or others for events in that lifetime. This is particularly useful when the other person is understood to be present in the current lifetime also. Taken symbolically, this part of the client’s waking dream still functions as a “corrective emotional experience.” For example, for the client with an overly strict superego who believes his/her mistakes are unforgivable, the non-judgmental acceptance experienced “in the light” combined with the experience of forgiving self can be quite intense. For the client with a rigid view of what is and is not possible, the virtual reality of these hypnotic experiences can provide alternative solutions/responses to problem situations than have previously occurred in his/her real life.

- Clients who feel victimized often have difficulty perceiving a current life problem from more than one perspective. The strategy of cognitive reframing can work well for those with better left-brain, analytical skills. Logic and analogy do not work as well for the “feeling” client. Drawing on the ability of hypnosis to bypass the “critical factor” in which the logical brain dismisses certain ideas as impossible, both models provide clients with experiential reframes that are affectively congruent with the content. One such client with a long history of feeling victimized had imagery in which she fled for her life from a medieval town as a young teenager. At the author’s suggestion, she went back to a pre-birth scene for that “life.” She experienced talking with the woman who functioned as her mother in that life. The client reported the two of them were laughing hysterically at how funny they both thought it was that she (the girl) would be running into the woods as a teenager to flee from those who were chasing her on horseback! Changing the attributions one attaches to an event automatically alters the resulting feelings (Miller & Wackman, 1982). The victim definition begins to transform when the person experiences the same kind of event from a radically different perspective. Many clients report past-life experiences in trance in which their role as the antagonist alters their current life view of both the victim and the aggressor. Another client was still angry at her dead partner for leaving her (cancer). In her imagery of an earlier lifetime she was also with that partner, but that time the client died first. Having experienced being in both positions, she understood that each role contained both advantages and disadvantages emotionally. Her anger at her dead partner subsided considerably after this experience.

Case Studies

Drawing on case studies from the author’s clients, the remainder of the article explores the applications of this four dimensional model to several themes that the author finds often emerge in past-life imagery:

- Clients sometimes demonstrate sudden, durable reduction or resolution of various Axis I symptoms.

- Clusters of lifetimes emerge in which a particular person from the client’s current lifetime is described as being present in the other lifetimes.

- Lifetime clusters sometimes emerge which deal with a particular theme that is part of the client’s problematic way of perceiving relationships or life in general. The scope of these ranges from specific (e.g., jealousy) to transpersonal (e.g., a belief in hope) in magnitude.

While not a focus of this article (see Schenk, 1999, 2006), it is important to note that past-life type imagery often involves metaphysical components. Many clients describe contacts with spirit guides, guardian angels, etc. Some, as in the anecdote about Thomas above, are visible to the client during hypnosis; others are not. Clients describe the information and advice from these contacts as consistently non-judgmental, supportive, and constructive. Some report messages from these contacts that are targeted to the therapist rather than the client. For example, a “guide” may offer the therapist a caution about the importance of dealing with a specific issue with the client. Again, note that neither the therapist nor the client are required to assume this information comes from a guide. As with the earlier analogy involving “Thomas,” the information is quite useful even if it is assumed to be coming from the client’s unconscious. For whatever reason, clients consistently pass along this information, even though it usually refers to an issue the client would rather avoid.

One of the most striking applications of past-life therapy techniques is in treating specific phobias. Unlike fears that are reality based in prior traumatic experiences in the client’s life, phobias are seen as irrational fears because there is no known antecedent (the BASK model) to account for the intensity of the fear. The irrationality disappears when a past-life origin of the fear emerges. Once the origin is found, the therapist can utilize a variety of traditional trauma treatment strategies to resolve the fear as would be done if the origin were from the current life. A traumatic death experience in a past life often includes intense emotions during which the person made decisions about himself/herself in relationship to others. These then function as state dependent memories (Rossi and Cheek, 1988) in the current life. In this vein, Woolger (in Lucas, 1993) notes the importance of completely addressing all four components of any traumatic memory:

- Physical/somatic/body

- Cognitive

- Emotional

- Existential meaning

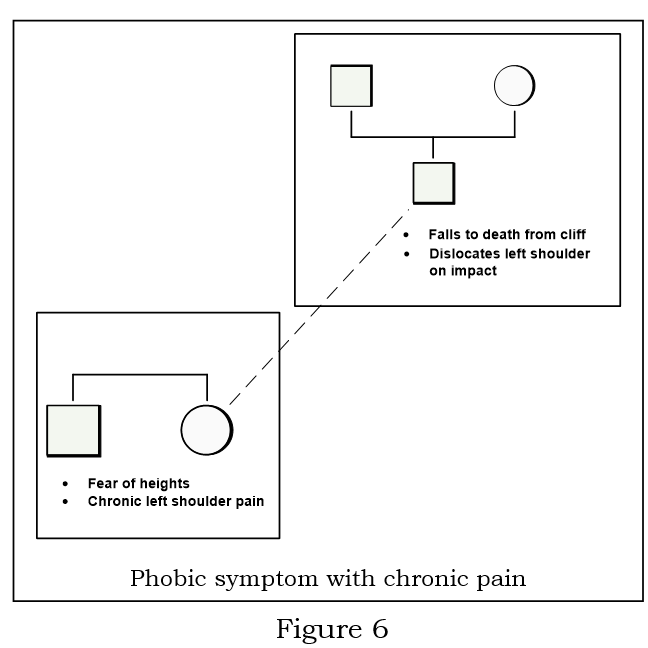

Case 1: Chronic left shoulder pain and a fear of heights

A variation on phobias involves physical conditions that do not heal as expected. One client presented with a chronic history of left shoulder pain and a seemingly unrelated fear of heights. Ideomotor signaling indicated there were origins from both the present life (which were known) and from a prior life. In past-life type imagery she experienced being a male American Indian who fell to his death one day while walking along a cliff. As the Indian floated above his dead body, he noticed his left shoulder had been horribly dislocated from the fatal impact. The author suggested the Indian and the woman dialogue about his final thoughts as he had fallen to his death. Both concluded that she had anchored in her own shoulder his thought, “Be careful when walking along high places: you could kill yourself with one wrong step.” He agreed that having experienced his life and death, she could effectively hold this wisdom in her consciousness rather than in her shoulder. Both her fear of heights and shoulder pain resolved following this experience, and had not returned after several months. Her four dimensional genogram is shown in figure six.

Case 2: Multi-life relationship problems

The varied sources of intense relationship difficulties are well recognized by both couples therapists and family/systems therapists. Like phobias, sometimes the origins seem not to be adequately explained even after taking a careful family history of both partners. In such cases the added information from layered genograms sometimes holds the missing information that allows resolution of the conflict.

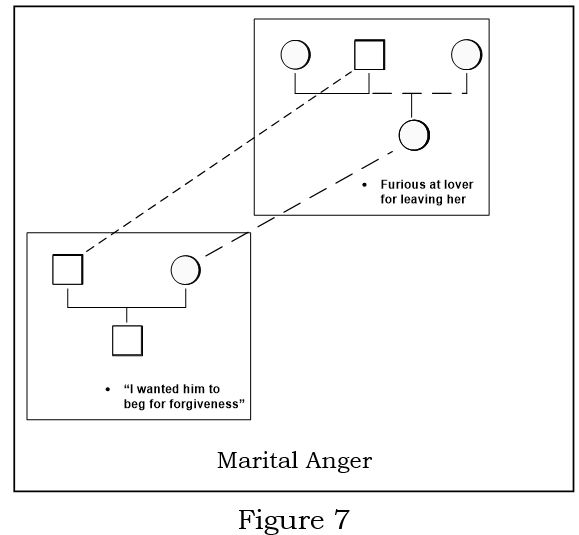

One couple (Charles and Leigh) presented for marital work because of the woman’s intense anger towards her husband: “I wanted him to beg for forgiveness when he came home.” While he agreed some of it had been clearly warranted, both concurred his past behaviors (which he had since changed) did not adequately account for all of her anger. After exploring possible origins in traditional ways, the author used ideomotor signaling to inquire about possible past-life factors. She subsequently had three past-life type experiences, one each involving her son, her father, and her husband. In the last one she had an affair with a man who was separated from his wife. She had hoped that becoming pregnant would cement her relationship with him. However, he returned to his wife instead. She died right after giving birth to a daughter. “I never forgave him for that; he left with somebody.” As she explored the soul level decisions following her death she was able to release her anger. The next week she reported that her anger towards Charles had completely subsided. At follow-up one year later, both she and her husband reported that her presenting intense anger had remained absent. Her dual genogram is shown in figure seven.

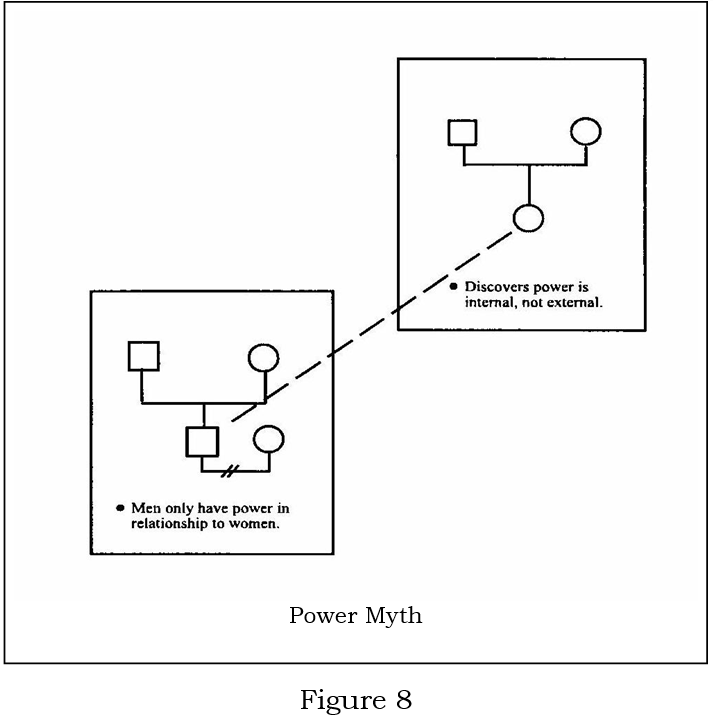

Case 3: Multi-life experiences involving the same theme (power)

When a theme is experienced in several lifetimes, there are usually important variations and subtleties that transform the concept for the client. Often, the effect is to take a term that the client had previously defined in a narrow way (e.g., power) and through several past-life experiences come to understand the term as existing along a broad continuum. External labels such as “victim” cease to hold much meaning by themselves. Instead, the client discovers through these different lifetimes that it is the internal personal experience of the relationship that is critical. The struggle for control shifts to an internal one in which the client is faced with choosing to hold on to old beliefs (e.g., feeling victimized), or shifting to the new beliefs experienced during hypnosis which produce contentment, calm, and inner peace. The affective richness of the trance experiences seems to combine the best of virtual reality (without the hardware or software) with the cognitive logic of how changes in attribution lead to changes in feelings. The importance of the emotional component of these images can not be overstated. The cognitive component of the experience seems clearly secondary to the emotional component. That is, the cognitive shifts follow automatically from the (emotional) experiences.

One male client from a Jewish background had grown up with the belief that women possess “magic” and men do not. Therefore, he believed that in order to have access to it, a man has to be close to a woman. As a result, when the client found himself between relationships, he experienced considerable anxiety. In one session involving past-life type imagery, the man experienced himself as a nun who lived her life in a convent. Even as a child, the woman had understood that her father was afraid of power and of misusing it. Her father had brought her to the convent, in part, so that she might pray for family fortune, the success of people close to him, etc. As might be expected, her early memories of the convent were of feeling excluded from the world outside. Referring to other teenagers she said, “They are allowed out of the cell, this room, and I am not.”

As the imagery continued, the client reported a major shift: the young woman had experienced separation as a kind of exile, but suddenly had the experience “that God missed me.” The client periodically interjected his own observations about correlations between physiological aspects of the hypnotic experience and memories of some of the Psalms from the Old Testament which had long held meaning for him. As he experienced being the nun, he described a kinesthetic sense of his throat area knowing what was true (“love”), as contrasted with his mouth area (“fear”) which he described as trying to dismiss what he was experiencing. He reported being quite moved by the parallels between his emotional reactions to the old Psalms, the young nun’s emotional experiences as she prayed, and his own physical reactions. In this context, the nun commented at one point, “All songs are the same song.”

When I asked if the client was willing “to explore the rest of (the nun’s) life,” he briefly reported about the tone of the nun’s adult life and then had a spontaneous OBE experience following her death. The nun, who had since become the Mother Superior of the convent, found herself talking with Jesus and Mother Mary. In a dialogue involving the client, the nun, and the other two, the client reported further insights. He had seen magic as something external to himself; something you go find and then get incorporated by it. As the nun, he had the experience of having created a space within himself into which the magic could enter. He also suddenly had the realization that power is just another form of magic. Taken together, these insights served to shatter his faulty assumption that only women could have magic (i.e., power). As he internalized these experiences and insights, he reported being “flooded with light.” Following the trance work he commented again about the “aha!” shift from perceiving power as something external to something internal. He remarked about the power of the contrasts of the two religious traditions, but even more so about the masculine-feminine contrast. In a follow up with the client two years later, he related several anecdotes which evidenced the durability of the shift regarding power, and also reported significant shifts in his spiritual practices. His dual genogram is shown in figure eight.

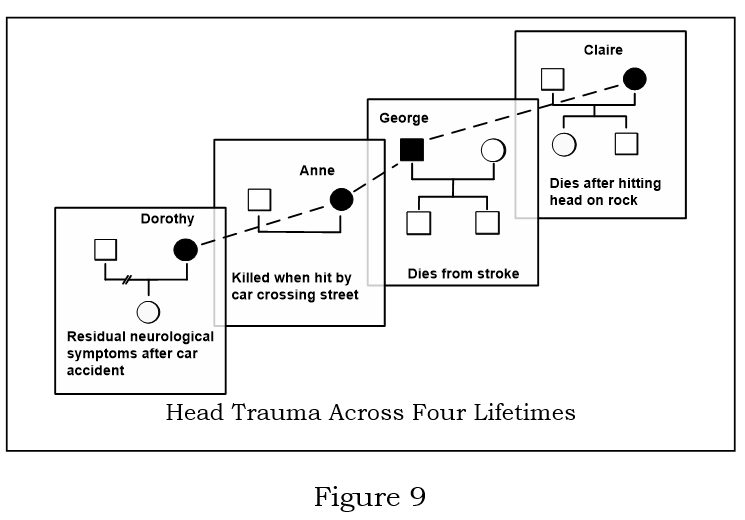

Case 4: Multi-life experiences involving head related trauma

A traumatic event sometimes has the effect of putting life on hold for an extended period of time. Trauma can trigger grief because of a tangible loss or because of the shattering of a belief. One client, “Dorothy,” was referred by her neurologist some 18 months after a car accident that had left her with some unpleasant neurological symptoms such as periods of dizziness and confusion, the experience of tiring easily, and classic symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Over a series of months she had a series of past-life type experiences which incorporated symbolic aspects of how the accident had impacted her life. Three of these included a sudden death involving the head.

As a young widow (Anne) during World War II, she was struck and killed by a car while crossing a street as a pedestrian. As she floated above the body, the author asked her to notice her final thoughts. From a third person perspective the client reported:

She’s confused. She didn’t know, didn’t really know what happened and why it happened so quickly. She knows she was hit by a car, but doesn’t accept that her life is over. Too sudden.

This matched Dorothy’s own experience following her car accident. Prior to that she had led an independent life as a single woman running her own small business, a business that required considerable time spent in the car. Suddenly she had found herself totally dependent on others for such simple things as getting to a grocery store. She had found it quite difficult to accept such basic help from other people. In the imagery Dorothy first helped Anne resolve her confusion and disbelief. Then in exchange, Anne offered to return the favor.

She wants to help me. She sees my cloudiness, my confusion. She doesn’t think she can clear it all by herself. She’s touching my head, giving peace and happiness. She keeps embracing me, telling me to be strong, to keep working at it…She wants to keep helping me. I see her saying she’ll be with me, watching. She’s extending her hands, touching my head to try to make things better. I feel calmer when she touches me. Almost like we’ve gone from being friends and companions to her watching for me, her taking care of me. (Is that okay with you?) Yes. I trust her.

At this point the author created an operant conditioning cue anchoring Anne’s calming touch as a response to future feelings of cognitive cloudiness. Then he built on the idea of Anne as a resource by inviting her to notice if there were others who could help.

T: Then in the future if you are feeling some of that cloudiness, can she come and touch your head to restore that sense of calm and peacefulness?

C: Yes. I was there for her to help her; she’ll do what she can to help me. Now our roles are reversed. She’ll help me find a way back as much as she can.

T: As you helped her to find her husband, can she bring others to you who may also help?

C: Yes. There is an aura of purple around her helping her. I don’t see anyone behind her but I feel tremendous help through her for me. I catch glimpses of my (current life) father (who died a decade earlier) now and then; the rest is just an energy or aura around her. It’s very big. It’s all very positive, very loving, very warm. They want to do all they can…I feel she and everyone with her will really be there for me. They won’t be able to do it all. Telling me she won’t do everything, but will always be there whenever I need her. They’ll be there to give me strength, guidance, the capacity to go forward.

Dorothy returned to the theme of sudden loss in her next waking dream. In this one she was a man, “George,” who had married and raised two children. In his later years he suffered a stroke that left him unable to speak for the few days before he died. She noted that “he didn’t feel robbed because his life ended early. He’s just sorry he couldn’t talk with his family at the end.” That led into a dialogue between Dorothy and George in which he cautioned her:

He’s telling me to not let that happen to me. To always express my emotions and feelings every day, because you don’t know if you’ll have a next time to talk with people…Again, he expresses sorrow at not being able to express himself at the end. He tells me to really work at what I’m going through now so that I don’t have to go through these limitations.

I see George and Anne now, both there to help me. What happened to them is not to be reflected in me…I feel like they’re telling me there are other lives. They are happy I’ve recognized in my own experience the value of what’s important and what isn’t – the people we love and not possessions, not work. An understanding of the value of life. They’re saying it will enrich my relationships with family and friends. This deepens them even more than before. I’ve learned to give up fear by being willing to ask for help. It’s sharing of help whenever anyone needs support. They say I need to get more rest so my brain can heal even more.

At the end of that session she commented again how difficult it had previously been for her to accept help. The clear message she heard from Anne and George went in at both the literal and metaphorical level: “It’s okay (to ask for help). We’re happy to do it. You’ve done it for us.” As our work continued in the months that followed, she confirmed that it has become easier to ask for help and to accept it when offered.

Three months after her waking dream as Anne, Dorothy returned for a second look at Anne’s life. She focused on the time period between her husband’s death and her own death. This dream sequence helped punctuate a theme which was to re-emerge in other dreams: The car accident didn’t kill you. You still have the option to go forward with your life. This theme emerged one more time in a past-life type experience as a painter, “Claire,” who lived in France. After her death as the painter she reported:

C: I see her telling me to start with a clean page…to paint my own life and my own beauty…with the softness and colors that I want. To go with my feelings…to go with the happy and bright colors: the yellows and the blues, greens…just a bit of purple. To feel free…to express myself freely. It doesn’t matter that I don’t have her techniques…just to paint what I feel…that it doesn’t take talent; it just takes emotion. I see her showing me the colors and shapes I would want, saying, “Just enjoy.” It’s like I see her sweeping her arm to the page I’ve painted that’s now big and large…covering our whole view…saying, “Now, go paint the rest of your life.”

T: She seems to have understood how happiness is a by-product of choices.

C: Yes. Yes, I feel that just in the choices I am making in my own life today how much calmer, happier, at peace I feel. Glad I’ve taken control again.

The client’s assumptions about control and loss played out in a series of past-life type experiences which facilitated both first order change as her depression lifted, and second order change as she gradually incorporated her changing beliefs and attitudes into her daily life. Her four dimensional genogram is shown in figure nine.

In this article the author has proposed adding a fourth dimension to family/systems models as one way of extending current personality theories and treatment strategies to account for results such as those in the four case studies presented above. As is hopefully clear from the excerpts used, neither the therapist nor the client needs to begin with a belief in reincarnation, nor does either need to attribute the hypnotic experiences to past lives for them to produce symptom resolution. The author’s own experience suggests that waking dream (i.e., metaphorical) imagery intermingles with past-life recall in trance. The same therapeutic tools are applicable to both kinds of imagery. Drawing distinctions between the two has not been a distinguishing factor where the effectiveness of treatment outcome is concerned. Both can produce significant Axis I symptom reduction and, over time, Axis II changes of a second order nature.

Applied research requires a theory or model with which to measure the degree of fit between expectations and observations. In proposing a model to explain experiences of the types described in this article, the author seeks to offer clinicians and researchers a theoretical basis for critically exploring the ways that these therapeutic tools may be useful. With both models to serve as a foundation, further research on the clinical applications of past-life therapy and/or waking dreams may become easier to articulate. Stevenson’s well documented studies of several thousand children who claim to remember past lives point to a variety of possibilities. In his 1977 article as well as in later books he has offered case studies of previous lives that could be categorized along several factors:

- phobias and philias of childhood

- skills not learned in early life (such as xenoglossy)

-

- abnormalities of child-parent relationships

- vendettas and bellicose nationalism

- childhood sexuality and gender identity confusion

- birthmarks, congenital deformities, and internal diseases

-

- differences between members of monozygotic (identical) twin pairs

- abnormal appetites during pregnancy

These and other presenting symptoms offer a rich variety of research possibilities to the interested clinician who is willing to venture outside the cultural dissociation barrier.

References

Abbott, E. Flatland: A Parable of Spiritual Dimensions. 1884

Almeder, R. Beyond Death: Evidence for Life After Death. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1987.

——— Death and Personal Survival: The Evidence for Life After Death. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1992.

Bowman, C. Children’s Past Lives: How Past Life Memories Affect Your Child. New York: Bantam Books, 1997.

Braun, B. The BASK (behavior, affect, sensation, knowledge) model of dissociation. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders. 1 (1), 4-23, 1988.

——— The BASK model of dissociation: Clinical applications. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders. 1 (2), 24-26, 1988.

Brown, D., Scheflin, A., & Hammond, D. C. Memory, Trauma, Treatment and the Law. NY: Norton, 1997.

Cardena, E., Lynn, Steven J., & Krippner, S. (Eds.) Varieties of Anomalous Experience: Examining the Scientific Evidence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2000.

Cerminara, G. Many Mansions: The Edgar Cayce Story on Reincarnation. New York: Signet Books, 1950.

Crabtree, A. Dissociation and memory: A 200 year perspective, DISSOCIATION, V (3), 150-154, 1992.

Fiore, E. You Have Been Here Before: A Psychologist Looks at Past Lives. New York: Ballantine Books, 1978.

Gershom, Y. Beyond the Ashes: Cases of Reincarnation from the Holocaust. Virginia Beach, VA: ARE Press, 1992.

Lucas, W. Regression Therapy: A Handbook for Professionals. Crest Park, CA: Deep Forest Press, 1993.

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R. Genograms in Family Assessment. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1985.

——— Genograms: Assessment and Intervention. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999.

Miller, S. & Wackman, D. Straight Talk. New York: Dutton, 1982.

Moody, R. Coming Back: A Psychiatrist Explores Past-Life Journeys. New York: Bantam, 1991.

——— Life After Life. New York: Bantam Books, 1975.

——— Reflections on Life After Life. New York: Bantam Books, 1977.

——— The Last Laugh: A New Philosophy of Near-death Experiences, Apparitions, and the Paranormal. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads, 1999.

Ring, K. & Cooper, S. Mindsight: Near-Death and Out-of-Body Experiences in the Blind. Palo Alto, CA: William James Center for Consciousness Studies, 1999.

Ring, K. Life at Death: A Scientific Investigation of the Near-Death Experience. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1980.

——— Heading Toward Omega: In Search of the Meaning or the Near-Death Experience. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1984.

Ross, C. The dissociated executive self and the culture dissociation barrier. DISSOCIATION, IV (1), 55-61, 1991.

Rossi, E. The Psychobiology of Mind-Body Healing: New Concepts of Therapeutic Hypnosis. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986.

Rossi, E. & Cheek, D. Mind-Body Therapy: Methods of Ideodynamic Healing in Hypnosis. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1988.

Sabom, M. Recollections of Death: A Medical Investigation. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982.

Sacerdote, P. Induced Dreams: About the Theory and Therapeutic Applications of Dreams Hypnotically Induced. New York: Theo. Gaus, Ltd., 1967.

Schenk, P. The Hypnotic Use of Waking Dreams: Exploring Near-Death Experiences Without the Flatlines. London: Crown House Publishing, 2006.

——— The Benefits of Working with a “Dead” Patient: Hypnotically Facilitated Pseudo Near-Death Experiences. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 42:1, 36-49, 1999.

Schwartz, G. The Afterlife Experiments: Breakthrough Scientific Evidence of Life After Death. NY: Pocket Books (Simon & Schuster), 200.

Stevenson, I. Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1966.

——— The explanatory value of the idea of reincarnation. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 164 (5), 305-326, 1977.

——— Research into the evidence of man’s survival after death. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 165 (3), 152-170, 1977.

——— Unlearned Language: New Studies in Xenoglossy. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984.

——— Children Who Remember Previous Lives: A Question of Reincarnation. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1987.

——— Reincarnation and Biology. Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1997.

——— Reincarnation and Biology: A Contribution to the Etiology of Birthmarks and Birth Defects. Volumes I and II. Praeger Publishing, 1997.

——— European Cases of the Reincarnation Type. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003.

Talbot, M. The Holographic Universe. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 1991.

Tucker, J. Life Before Life: A Scientific Investigation of Children’s Memories of Previous Lives. NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

Wambach, H. Life Before Life. New York: Bantam Books, 1979.

Weiss, B. Many Lives, Many Masters. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

——— Through Time Into Healing. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

——— Only Love is Real: A Story of Soulmates Reunited. New York: Warner Books, 1996.

[1] Ah, the challenges of conveying three dimensions in only two. Think of the genogram as being drawn on a piece of paper held upright. Think of the arrow showing the time dimension as the piece of paper moving away from you into the future. In figure 1, the arrow follows the traditional Western idea of time, moving left to right. In figures 2 and 3, I tried to draw it as I would on a graph with the z dimension, moving from lower left to upper right.

1 For the interested reader, McGoldrick and Gerson (1985, 1999) offer an excellent text on the use of genograms. As one of many famous case studies, their presentation of Jung’s family history elucidates clearly the history behind the merger of the medical and metaphysical in his work.

2 Handled in this manner, hypnotically facilitated “past life” experiences also avoid the problems associated with lawsuits and hypnotically refreshed memories.

3 It is important to remember that clients are never themselves in these hypnotic experiences. They always report being someone else. The author never projects clients forward to their own death in the current lifetime.