Core issues underlie behavior, says this author. When using past-life regression therapy (PLRT), she advises, it is important to address the client’s case from an overview position, using the client’s response to a theme to focus the session on a search for the core of a behavior pattern instead of the surface presenting problem. The purpose of PLRT then is to remove the subconscious reactive part of a traumatic past-life experience, putting the individual in present time in a position of conscious choice instead of reactive programming.

Core issues underlie behavior, says this author. When using past-life regression therapy (PLRT), she advises, it is important to address the client’s case from an overview position, using the client’s response to a theme to focus the session on a search for the core of a behavior pattern instead of the surface presenting problem. The purpose of PLRT then is to remove the subconscious reactive part of a traumatic past-life experience, putting the individual in present time in a position of conscious choice instead of reactive programming.

A core issue may be defined as a viewpoint or feeling that motivates behavior. A core-issue incident is an experience that causes an individual to form a viewpoint, feeling or emotion that originates a pattern of behavior. Primary core issues are: anger, fear, control, worth/worthlessness, good/bad, power/helplessness, trust/betrayal, loss, guilt, etc.

There may be one primary core issue active in a specific lifetime and any number of secondary issues associated with it or derived from it. For example, concepts of “good” and “bad” are usually formed early on the time line of the reincarnation cycle. There can be a number of lifetimes when, because of entirely different circumstances, the individual may have concluded that he (or she) was bad, and then associated other viewpoints around this core issue, programming and cross-referencing them on the same tape in the memory banks. These are the secondary core issues.

Once the viewpoint of “bad” is assumed in the present lifetime, it stimulates again the entire tape, and the individual reacts subconsciously to the program. The core decision and the secondary core issues then form a pattern of behavior. A program model could look like this:

Core-issue decision: I am bad. Secondary core-issue viewpoints: When I’m bad I’m not acceptable…I need to be accepted…I need to be good to be accepted…I can’t let myself make a mistake…I have to do what they tell me so I won’t make a mistake…If I don’t make a mistake they will accept me…If they accept me, I will be good. The individual, reacting to the core issue, may then become a compulsive, people-pleasing adult, rigidly structured, always afraid of making a mistake, always going outside of her or himself in an effort to feel “good” about who he or she is.

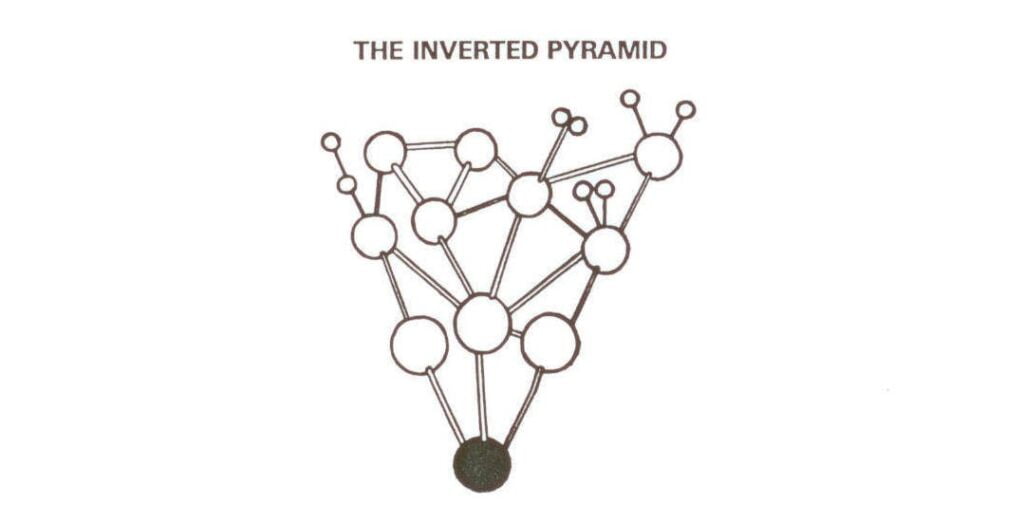

Through elaborate machinations based on the viewpoint “I am bad,” the individual has created a massive, inverted pyramid in an attempt to cope with one core decision. As we unravel the various skeins of this complicated reactive pattern to get at the primary core issue, we find that it did not begin with this lifetime; we must go further back.

THE CONCLUSION “I AM BAD” (represented by the black sphere) CREATES A MASSIVE INVERTED PYRAMID OF ASSOCIATED FEELINGS AND VIEWPOINTS (represented by the white spheres) IN AN ATTEMPT TO COPE WITH THE ORIGINAL CORE DECISION. OFTEN THE PRESENTING PROBLEM WILL BE ONE OF THE SMALLER SPHERES AT THE TOP OF THE PYRAMID.

THE CONCLUSION “I AM BAD” (represented by the black sphere) CREATES A MASSIVE INVERTED PYRAMID OF ASSOCIATED FEELINGS AND VIEWPOINTS (represented by the white spheres) IN AN ATTEMPT TO COPE WITH THE ORIGINAL CORE DECISION. OFTEN THE PRESENTING PROBLEM WILL BE ONE OF THE SMALLER SPHERES AT THE TOP OF THE PYRAMID.

More than one primary core issue may be re-stimulated in a lifetime. For example, fear and guilt may be inexorably linked in the present, but may have originated in different lifetimes and must be dealt with individually by the therapist.

Locating an Original Core Issue

The following case history illustrates how an original core-issue incident can be located. When this 26-year-old client first entered my office, his hair, eyes, skin, clothing and demeanor all appeared to be brushed in the same, dull monotone. He had never married, had not dated for years and had worked at the same job since graduating from college. As a child he had been severely abused by an alcoholic father.

The client was living an excessively structured life and was becoming agoraphobic. He had to drive to work on exactly the same route every day; his house had to be immaculate, with nothing out of place at any time; shirts had to be hung on a specific hanger in a specific place in the closet; socks were always put in exactly the same position in the same drawer. What seemed to epitomize his compulsive behavior was that when he finished brushing his teeth, he had to tap his toothbrush on the edge of the sink exactly four times, no more, no less. His sister, based on her own experience with me, convinced him to try PLRT (past-life regression therapy).

It is important to find the first feeling associated with compulsiveness in the present life, because that is the trigger, not the cause, of the reactive program. The ensuing behavior augments the pattern.

The feeling of fear associated with the viewpoint “I can’t change my route” was the earliest signal of compulsive behavior my patient could recall in the initial interview. When he was a boy and all of his friends wanted to go to someone else’s house after school, he couldn’t go with them — it would have taken him on a different route home.

He soon moved into an earlier lifetime as a 32-year-old male of minor nobility during the French Revolution. There was rioting in the streets and his servants had all deserted him. He managed to get the horses hitched to the carriage; then, grabbing what valuables he could lay his hands on, he got his wife and two children into the carriage and headed out of the city on his planned route of escape. As he raced down the street he heard the mob coming closer and veered from his route. At this point in the narrative he stopped speaking.

Th: What’s happening?

Cl: (after a pause) They got us by the wall.

Th: What does that mean?

Cl: They pull us out of the carriage. Oh my God! They’re beating us to death!

Th: What emotions are you feeling?

Cl: Rage…injustice…terror…

Th: Just before the body dies, do you make any decisions?

Cl: I’ll never change my route again. If I do, we’ll all be killed.

After moving through the body-death experience, the client began to feel cold and to shake visibly. I allowed him to continue with this kinesthetic response as the repressed energy from the experience began to dissipate. To discover the trigger that reactivated the program, I moved him forward to the point just before he was to inhabit his present body and asked him to “locate the earliest incident in the present life that caused you to feel, ‘I can’t change my route.’” He moved to an incident at the age of 2, when his father, in out-of-control rage, beat him mercilessly. This triggered the program from the lifetime in which he was beaten to death in France, with all of the associated viewpoints, including the conclusion that if he changed his route he would die.

With conscious recall and the energy released, the client cognitively realized the cause/effect relationship and was able to separate the past from the present. He understood that his childhood would have to be confronted and that the rigid structure of his life would neither alleviate his fear nor resolve his problems. He left the session feeling elated and full of energy.

Several days later his sister called me in distress. On a visit to his apartment she had found dirty dishes in the sink and clothing strewn on the bedroom floor; the house had not been cleaned for days. She was amazed at my delight until I explained that the compulsive pattern and the associated behaviors had been released. Historically, when a client resolves an issue, the behavioral pattern is like a pendulum that has been locked in one extreme position and then let go. The client tends to move to an equally extreme opposite position until he is stabilized at the center — the normal behavior.

The core of the compulsive behavior on the part of this client was eliminated in that one session, but only one facet of the fear had been addressed. In ensuing sessions we continued working on that fear and on the remaining core issues that had been so unhappily reactivated by child abuse.

To attempt to reach the original core incident immediately usually causes the subconscious reactive mind (SCRM) to become overwhelmed. That is why focusing and peeling the layers and facets from the core issue before reaching the causal lifetime is necessary for complete resolution of the problem.

Focusing

The time track is vast, and the mind cross-references information; so definitive focusing is necessary if a session is to resolve a specific problem. Lacking focus, both client and therapist will find themselves lost in a labyrinth of lifetimes without a map. Focusing is particularly important when dealing with core issues, because they are so multifaceted, so interconnected, and because there are so many lifetimes associated with them.

Presenting the SCRM with complex generalities and undefined feelings or viewpoints usually results in kaleidoscoping pictures, irrelevant lifetimes, and frustration for both therapist and client. The most effective method for identifying a theme or focus for a session is to actively listen during the client interview for the following: words and phrases out of context; illogical sequences of words and thoughts; phrases charged with emotion; words often repeated; phrases that create changes in body language or verbal tone.

Then the therapist should move the client into the altered state, reading off the phrases that stood out and asking the client to identify the most meaningful one, the one that causes a gut response. The phrase selected by the client is then repeated during the session, acting as a trigger for the SCRM to access the associated lifetimes as well as the present-life trigger incident.

Positioning in the Lifetime

The SCRM can cross-reference and respond to directions, but it does not reason; in the altered state it is literal. With accurate focus and theme, the client will frequently move into a lifetime in the middle of the incident associated with the theme. If this occurs, and the client seems to be going into overwhelm, the therapist can simply direct him to an earlier period in that incarnation and ground him in the lifetime by having him feel his feet and the parameters of his body. Then he can be moved forward and positioned at the beginning of the incident. It is effective to move the client in both body and feelings, and to then have him move through the incident.

If a client, after being grounded, goes into a lifetime too comfortably, he is likely to stop speaking or just meander. For the therapeutic purpose, it is important to get him to the source of the problem. This may be done simply by asking him to locate the significant incident that causes… (repeat the words of the theme), moving him to the beginning of the incident and then through to the end.

PLRT is client-centered; but, because of the interaction with the SCRM, it needs to be more directive than conventional therapy, which often uses the thinking, cognitive parts of the mind. When PLRT is applied to a client in the altered state, the SCRM needs to be directed to specific lifetimes and specific incidents in those lives. During closure, at the end of the session, the analytical and cognitive functions of the mind can be utilized.

With PLRT, the SCRM is structured in the following manner: An individual encounters a negative experience in a lifetime, reaches a conclusion and makes a decision. This becomes the original core incident of a survival program. Thereafter, every similar experience and every related decision of all ensuing lifetimes are cross-referenced onto the same survival program and, when triggered, can cause an unconscious, reactive response.

Therapist Difficulties with SCRM during PLRT

When the client is in the altered state, the therapist must never offer evaluations or opinions. Since the SCRM does not reason, such pronouncements would go directly into the subconscious without any deliberation on the part of the client, adding confusion to an already complicated program.

Suppose, for example, that a client in an earlier lifetime experiences an upset with his mother, and the therapist interjects, “You must be very angry with her.” The client will usually respond by agreeing, overlaying his/her actual feeling — which could be fear — with anger. Or if the therapist remarks, “That was a good thing for you to do,” but on a deep level the client feels guilty, he/she will cover the truth over with the therapist’s input, clogging the way to resolution of his/her guilt feelings.

The SCRM is literal, so it is important to generalize all words as much as possible. For example, telling a regressed client to look at his shoes, only to find that his feet are bare, may not only confuse him but may move him out of alpha into beta. Similarly, directing a client to find his house during a lifetime as a cave dweller, or to walk to a town when he happens to be on a ship, will be counterproductive.

The SCRM is also linear in function. If the therapist asks too many questions at once — e.g., “How do you feel? What do you do next? Why did you do that?” — the client may become confused, or even move out of the experience altogether.

One additional caution here: Asking “why” questions forces the client into his analytical mind and may pull him right out of the regression.

Vertical and Horizontal Approaches

The therapist can take the client vertically or horizontally through lifetimes; both ways are effective for healing negative core-issue patterns. The issue can be addressed horizontally by locating a significant earlier lifetime associated with the phase linked to the core issue, and then directing the client to the specific significant incidents that caused the feeling or viewpoint in that incarnation. Examining birth and death experiences can be important for completion and release of that lifetime on the core-issue chain.

To move vertically in quest of the core-issue incident, the therapist begins in the present life with the significant circumstance which triggered the feeling, and then moves the client continuously back in time. Clients may focus on other incidents in the present life, or immediately move into previous lifetimes. With each lifetime, the therapist locates only the significant incidents associated with the theme, and then moves into earlier and earlier incarnations. The premise is that each lifetime is linearly connected on the chain that leads to the original incident and the decision resulting from it, which initiated the pattern of behavior.

It is important to remember that the client does not always make a conscious decision or draw an obvious conclusion. If this is the case, the therapist simply moves on with the process. Frequently, at the end of a session, as the client begins to use the cognitive faculty to link the lifetimes together, decisions or conclusions will become clear. Both methods are effective, although the horizontal method is usually more attainable with first-time clients. The decisions should be located, and with either technique, the present-life trigger should be identified — unless the client completes the process spontaneously.

The concept of a core-issue linear-vertical approach to access a causal lifetime is demonstrated in the following case history:

The Linear-Vertical Approach

The client was a woman in her mid-40s, and the presenting problem was a bad complexion. During the initial interview, the out-of-context phrase the client verbalized, and later selected as the focus, was, “It wasn’t worth it.” After a short induction, she was asked to locate a significant experience in the present life that caused her to feel that “it wasn’t worth it.”

The client found herself in the sixth grade at school, where she had a crush on the teacher and wanted to please him with an excellent term paper. She spent long hours agonizing over the paper, and during the process broke out with pimples over most of her forehead. Although she got an A on the paper she was extremely unhappy about her complexion and felt “it wasn’t worth it.”

Moved to an earlier lifetime, she finds herself in 1621, a friar in a monastery, surrounded by rolls of parchment. For more than a month, the bishop has been pressuring the friar to complete his job of copying original documents. The anxiety grows, and eventually the friar’s body breaks out in boils. Although he completes the task and the bishop is pleased, the boils remain, and the friar feels that “it wasn’t worth it.”

Going to a still earlier lifetime in search of the cause, the client again finds herself in a male body. He is in the Mediterranean area in 39 B.C., surrounded by dying soldiers and piles of cloth filled with yellow pus. He is a doctor, exhausted after weeks of trying to save lives so the king can use these men again in his battles. A disease has broken out, causing pus-filled sores on the soldiers’ bodies, and the doctor has a sense of defeat, having pushed himself almost beyond human endurance on this hopeless task. Looking at his surroundings, he concludes that “it wasn’t worth it.”

After reliving this experience, the client felt a surge of energy, indicating that she had reached the origin of her problem, and she began the cognitive process. She realized that in 39 B.C. she had felt great anxiety trying to save diseased men to please the king; in 1621 her anxiety to please the bishop had resulted in boils all over the body; in her present life she had agonized over her term paper to please the teacher and had broken out in pimples all over her forehead. She saw that she had always overextended herself to please other people because of a need for approval. Her mind had cross-referenced anxiety/need for approval/pustules, the pustules being an automatic body response to anxiety.

Her complexion began to clear almost immediately after the session, but it was obvious that her skin condition wasn’t the basic problem. The core issue was worth/worthlessness, and the associated feelings and viewpoints were: “I have to please them”; “I have to be good”; “I have to do it right”; “I have to be perfect to do it right”; “I’m not worth being loved”; “I will do anything to try and be accepted.”

The presenting problem and one of the associated viewpoints, “I have to please them,” was handled in that first session; and, realizing the value of PLRT, the client stayed in therapy to deal with her worth issues. Today, four years later, the entire focus and experience of her life has altered in a dramatic and positive way, and the pustules have not returned.

To free the being from the encumbrances of negative energy patterns, the therapist must deal with the core issues causing the negative behavior. The case must be addressed as a whole, with the therapist in an overview position — one that is not limited to the presenting problem.