by Hans Ten Dam, M.A.

While regressing to the causes of psychological and psychosomatic problems, says this author, we sometimes find chronic adverse conditions, rather than specific traumas. In his own practice, he has found that these cases call for a somewhat different treatment—that instructions to relive the adverse conditions can actually worsen the symptoms. This article differentiates “hangovers” from “traumas,” presenting some general insights into hangovers and a method of dealing with them. A case history is offered in illustration.

While regressing to the causes of psychological and psychosomatic problems, says this author, we sometimes find chronic adverse conditions, rather than specific traumas. In his own practice, he has found that these cases call for a somewhat different treatment—that instructions to relive the adverse conditions can actually worsen the symptoms. This article differentiates “hangovers” from “traumas,” presenting some general insights into hangovers and a method of dealing with them. A case history is offered in illustration.

In regression therapy we look for the unassimilated experiences whose repercussions have carried over into present life. These are usually called “traumas.” But that label does not fit a whole range of repercussive conditions I have seen in my practice—obsessions, pseudo-obsessions, alienation, character postulates (rigid programs, often belief systems, usually expressed in key sentences) and what I term “hangovers”—each of which calls for a different treatment. Here I want to talk about hangovers.

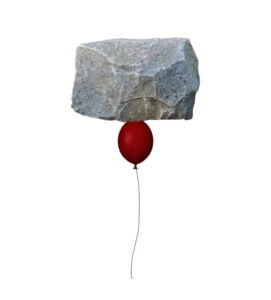

A trauma begins and ends at a specific moment. It is a precise episode, charged with negative emotions, in which the ego collapses. A hangover comes from a situation that caused a more general kind of misery. The ego is pinched off and diminished, like a bonsai. It is almost stagnated by long weariness, pressure, despondency, and depression. Fear, anger, and grief are intense, acute emotions, but boredom, weariness, and depression are chronic and diffuse. They do not produce a trauma, a wound, but rather a hangover, a dead weight, a “dirt skirt.”

Dying from starvation is different from being starved all your life. Cold may be traumatic after you have been assaulted, injured, and then left behind in a wood; you have pain, you are cold, you feel lonely. But that is something different from a marriage that has always been cold.

Hangovers grow gradually. They have chronic, not acute, causes. It is as if you are invaded by mist or grit or dust or dirt—or by something sticky or shiny. An example: I come home from work. I am tired and irritable. I need an hour or so to restore myself with a book in my hands, a cat on my lap, a cup of coffee or some music. In other words, I have a hangover. It may be related to the chatter in my office, my uncomfortable chair, the smell in the corridor, or any combination of these. Or it may be pure boredom and distaste for the work I do.

That hangover clings to me like a mental dirt skirt. It dissolves but slowly, or it may even grow thicker. If I am so listless that I no longer regenerate, the process reinforces itself. I may dream about it and wake up feeling heavy. Or I may decide to leave my job, and that decision cheers me. I go whistling to my office. And precisely because I don’t care any longer, everything goes fine.

A hangover may trace to a perpetual battering of the ego. An enslaved person, for example, finds the challenge too heavy to respond to. Despite opportunities, he lacks the energy to escape, or even to think of it. Boredom and cynicism can corrode the energy. A cynical attitude often derives from a previous life as an intelligent and powerful person. It is a defense against being crushed by the weight of an imperfect world. When we can look at our own cynicism with some irony, however, induration may be limited.

I discovered the difference between traumas and hangovers from patients who did not respond well to normal trauma techniques. But the distinction seems not to have been appreciated in the literature on regression therapy. An exception is Brian Weiss, who writes in Many Lives, Many Masters (p. 42):

What I did not yet fully appreciate was that the steady day-in-day-out pounding of undermining influences, such as apparent scathing criticisms, could cause even more psychological trauma than a single traumatic event. These damaging influences, because they blend into the everyday background of our lives, are even more difficult to remember and exorcise.

The basic charges in most traumas are pain and fear. Basic charges in most hangovers are compulsion, repulsion, impotence, and weariness. We go to the wall; it wears us down; it makes us smaller, slower, heavier, and gloomier.

______________________________________________________________________________

Here are the most common situations that produce hangovers and the charges contained in those hangovers:

HANGOVERS

| SITUATION | EMOTIONAL CHARGES |

| Abandonment

Duty Emptiness Force Harshness Imprisonment Isolation Loneliness Monotony Marrow-mindedness Obstruction Pressure Rejection Repression Slavery

|

Being fed-up

Boredom Depression Disappointment Dissatisfaction Indifference Irritation Listlessness Melancholy Obstinacy Passivity Rebelliousness Repulsion Timidity Unhappiness Vacuity |

| INTELLECTUAL CHARGE | SOMATIC CHARGES |

| Cynicism

Distrust Doubt Ignorance Incapacity Incomprehension Insecurity Suspicion

|

Deformity

Discomfort Ugliness Weariness |

Natural ways to restore ourselves are relaxing, jogging, sleeping and dreaming, or doing something else we really like to do. Hangovers that interest us as therapists are those that are not cured by daily activities—usually hangovers from past lives.

A good death is the greatest catharsis. And part of a good death is getting rid of a worn-out body. We all have some hangover, simply from living in a body in a physical world that dispenses disease, hunger, weariness, restrictions, and pain—a world that puts a weight on our mind, a callous on our soul. The body gives us much, but most of us feel better without it. The hangover of the incarnate state is especially strong if we become old and tired after a life of toil.

Few things refresh like a good sleep, and nothing like a good death. But just as we sometimes wake up in the morning feeling broken, so sometimes we come into a new life with much of old life still weighing down on us. This is a hangover, gradually built in that past life. We may wake up heavy in our new life. We are low in energy. The central charge of many hangovers is impotence, and the main clutch of impotence is usually rancor. By fostering rancor, we remain victims, so that we may indulge in self-pity and do not need to change our behavior.

To the therapist dealing with hangover I would say: Go for whatever is most present, most immediately available with the patient. If there are many problems, many negative charges, without any clear priority, then go first for the free traumas and the free hangovers—those that are not anchored in character problems Character problems show themselves in repetitions from life to life, usually in one of five roles: victim, persecutor, helper, perpetrator, or neutral observer.

The most natural order of treatment is: free traumas, free hangovers, character postulates. But choose the order that liberates the most energy along the way. Sometimes we must eliminate the tough dirt skirts before traumas can be resolved. If we feel tired and empty for a long time, our capacity to experience deep emotions, even to feel wounded, is depleted. We become mechanical and musty. Then even a successful regression to a traumatic situation will produce no catharsis, because the trauma is embedded in a thick, tedious dirt skirt.

A case in point: A client regresses to a lifetime as a woman in 13th-century Germany. When people discover that she is pregnant, they beat her up with sticks—clearly a traumatic situation. Yet she experiences the whole thing numbly. She always lived under pressure, always got a good hiding, and was always threatened with punishment by other people or by the church. That beating is just the culmination of a lifetime of toil and repression.

It is much the same with persistent sexual abuse. Resolving the traumatic moments does not produce liberation, because these moments are embedded in a mass of negative experiences. We will not succeed in removing the traumatic charge until we have cleared up a large part of that mass and emotional vitality is increased.

Diagnosing the Hangover

We identify hangovers by the special charges listed above in the table.

Recurrent sentences with “always,” “never,” “nobody,” “everybody” are keys to either hangovers or character postulates. Super-generalizations have their origin either in the length of the original experience, or in a programmed self-image or world-image. If your patient says: “I feel unhappy,” and repetition and completion of this sentence get no results, then try, “I always feel unhappy.” Sometimes that produces a regression to the source of a hangover.

Sentences with “I am” often indicate a character postulate. A strong character postulate does make related traumas and hangovers repeat. Problems keep coming back, not by being locked in immutable conditions, but in accordance with a fixed program that is triggered over and over. “They always take it out on me.” “I’m not a lucky guy.” “I have two left hands.”

The difference is sometimes between “I feel” and “I am.” “I feel” indicates that the speaker does not identify with the feeling. I always feel unhappy implies that something makes him (or her) unhappy. But “I am always unhappy” shows that unhappiness has become a part of the ego. The first sentence suggests a hangover, the second a character postulate.

Identification is especially problematic when a hangover is reinforced by other people. The patient was a slave, and his masters were always shouting at him, “Hey, trash!” or “Come on, dog!” That may lead to, “I am a dog,” or “I am nothing.” A hangover is a mortgage on the ego. A character postulate is a problem within the ego structure, identification with a particular response pattern.

Another way to identify hangovers is to watch for these specific somatic complaints or phenomena at the beginning of a session:

Vague, shifting, unpleasant sensations

Feelings of stiffness

Vague heavy feelings

Feelings of weariness and exhaustion

Vague feelings of cold

Feelings of numbness or emptiness

Slow changes in posture

Slow rolling of the head

Slow facial expressions of repulsion

Curling up

Treating the Hangover

Treating the Hangover

The tenacious, amorphous character of a hangover poses a problem for the therapist. Patients often remain stuck in the reliving. The therapist has to tug harder, the catharsis is slower. Suppose my regressed patient is a woman slave who has been abused sexually for many years. She becomes less attractive, her teeth drop out, and finally she is dumped on the rubbish heap. If you tell her to “traverse it completely,” she will soon be worn out. Therefore we never give that instruction to a patient with a hangover. Rather, we analyze the physical, emotional, and intellectual charges and send the patient to specific situations that illustrate each charge: “Go to the moment of the worst weariness.” Then, go to the last moment you felt that weariness.” Then, “What else do you feel? Revulsion? OK, go to the first/the most/the last revolting moment.”

The life panorama after death is especially important in treating hangovers. It is essential that the patient be asked “How?” “What?” “Why?” and “Why not?” And then, “What still remains of that today?” This last question often brings out the most relevant charge, be it weariness, victimization or self-pity. The beginning and the long duration of each charge have to be understood, as well as moments of choice.

An essential question is, “What prevented you from changing your life?” Locate the decisive moments. If that is difficult, then go through the death experience to the “survey platform” to pinpoint those moments. Catharsis is unlikely without an adequate death experience, as a hangover is only a hangover when it remains a hangover after death. This implies that after death the patient moved “upstairs” only partially. But if that frustrating life was freely chosen, the death experience brings catharsis and the hangover dissolves rapidly.

The liberating steps in treating hangover are:

- Get an overall impression of the hangover course as a succession and combination of situations mentioned in the first table.

- Go through each situation to note such charges as helplessness, insecurity, submission, guilt, penance, revenge, etc. Take the next four steps for each charge separately.

- Go to the beginning of the charge. Ask, “What, precisely, did you experience at that moment? And how, precisely, did that come about?” It makes a difference if a slave grew up in a slave family or was a rich man convicted for murder. You need to know where, why, and how the inner dirt skirt grew. The patient tells you, “I am playing between the huts, and—O God! Slave dealers are talking to Mummy!” Thus you learn that the cluster of emotional charges related to slavery contains the feeling of being sold out and the feeling of distrust. The patient cannot even trust his own mother.

- Take the patient separately to the worst moment of each charge. You have collected, for example, coldness, monotony, and weariness “Go to the moment of the worst cold. Traverse it completely. Feel it.”

- Take the patient to the end of each charge, which often is death and sometimes never. Then you have a total picture of the situation: how it went, and what was its negative impact. But you are still not out of the woods. With traumatic situations it is not always necessary to relive the death experience, but with hangovers it is. The afterlife experience, too, should be gone through carefully.

- From the life retrospective, ask the patient, “What moments of choice did you have?”

“I tried to escape, but they found me and beat me up.”

Now you come to the essential point: “Go to the moment of choice. How did they find you? Could you have done anything to prevent that?” People often have unconscious programs that determine whether an escape attempt fails or succeeds. Good luck and bad luck exist, but usually they depend on the position of the inner magnet for luck.

If at this point the patient gains insight into the moments of his own responsibility, that insight is gold. He suddenly realizes that one right decision can prevent a lifetime of misery. He gets the feeling that “this will never happen to me anymore.” He sees what he did not see, or did not want to see, before. In a sense this is the completion of an incomplete death.

- Let the patient check on whether this particular charge is still with him in his present life.

Garrett Oppenheim takes patients to the place of overview, where he lets them look at their past lives on the left and the present life on the right so that they may find the connections between their various lives.

The facts by themselves are not decisive; it is how we experience them. And that often depends on why the patient lived a particular life. A freely chosen life of toil does not necessarily leave a hangover, because everything is assimilated right after death, with the exception of somatic charges.

If the moment of choice and personal responsibility can be found neither within the life nor in the retrospective after death, then seek it in the time before birth. A patient may exclaim, “O God, I don’t want to be born! This will be a horrible life. I don’t want to!”

“So why do you go anyway?”

“I have to. That man with those horrible eyes—he forces me.”

Do not be tempted to respond, “Ah, poor girl! I will now shower you with light, and you will be all right. That man will leave, and you will never again be forced.” Rather, ask, “Who is he?” And “Why do you let yourself be forced?”

“I cannot help it.”

“Why can’t you help it? Why has that man power over you?”

The patient says she accepted that power or could not resist it for some reason.

Direct her back to the origin of that acceptance or impotence. “We can always return to a moment of choice.” Compulsion is a characteristic of many hangovers; so catharsis, or liberation, is contingent on finding that moment of choice.

Curiously enough, hangovers, like traumas, may have positive side effects. A female patient who felt that she couldn’t really enjoy life—that she was always seeing the ugly side of things—regressed to a lifetime as a Jewish girl who died in Bergen-Belsen during the last winter of World War II. In the therapy session she saw directly in front of her eyes a transparent sheet imprinted with the image of the concentration camp. “I look at everything through that sheet,” she said.

In her present life, she grew up in a family of nature lovers, but always had difficulty enjoying natural, unspoiled environments. During the session she realized that she associated fallen trees and the like with the lack of care during that last winter in Belsen. And she now understood why she preferred well-trimmed parks and gardens. Nor did she feel any need to remove this hangover aspect. “Now I can enjoy parks even more,” she said.

When nursing her children (breast as well as bottle) she had always felt there was gold in the milk. After the appearance of the transparent sheet, she understood that she was comparing the warm baby milk with the cold and hunger of the concentration camp, and therefore felt the richness of that nourishment so deeply. She saw no reason to take away the sheet. “We all have a right to our own memories,” was the way she put it. Catharsis had brought her relief-producing insight. She had incurred no personal traumas, despite the terrible experience of Belsen, and she had died well.

A Demonstration Case

The following is from a demonstration session with a male subject in which I used a verbal bridge technique to uncover hangover lives.

Subject: “Leave me in peace. I have to do it alone.”

Therapist: Close your eyes and concentrate on that feeling. Can you evoke that feeling—wanting to be left in peace? (Asks for emotional charge)

Subject: Yes.

Therapist: How does it feel?

Subject: That you want to keep people at a distance, because they touch you too much.

Therapist: Where do people want to touch you? Try to feel it in your body. (Asks for somatic charge)

Subject: Somewhere around the heart. They want to touch my feeling.

Therapist: The urge to keep them at bay, how does that feel in your body?

Subject: Like pushing back.

Therapist: You still have that feeling?

Subject: Yes.

Therapist: Then we go back to get an impression of the situation in which this feeling began. I am going to count back and you come in a situation where you have the feeling that people want to touch your feeling and you have the tendency to push them back. You wished you were left in peace. We go back to the source of that feeling. I count from 5 to 1, and at 1 you make contact with it: 5-4-3-2-1. You want to be left in peace. Where are you and what happens?

Subject: The first impression is that I do healing work in a temple in Egypt.

Therapist: How do people pull at you? What do they want from you?

Subject: They want to get rid of their ailments without looking at themselves. (They could have been patients of a regression therapist!)

Therapist: Why does that bother you?

Subject: Taking away ailments, relieving pain, costs energy and peace. There are so many of them! (Implies weariness)

Therapist: If ever you attempted to decrease it you will get an impression of that now. (Looks for moment of choice)

Subject: I get the impression I didn’t try. It slowly increased.

Therapist: The number of patients slowly increased. You haven’t tried to lessen it, and your peace was gone. Go back to the moment you decided to do this work. Experience what you thought and felt. Where are you and what happens?

Subject: I get an impression I had once before. I sit on the forward deck of a sailing ship and decide to do something about healing.

Therapist: What goes through you while you take that decision? What do you feel?

Subject: Pity.

Therapist: Now go to the first moment you help someone and you feel what happens inside you. Where are you and what are you doing?

Subject: I get the impression of a temple. A stone table with people around it. Someone is lying on it. I am now allowed to magnetize. It feels as if my heart opens up. (Place of somatic charge)

Therapist: Leave this, and go back to the situation in which you felt consciously for the first time, “I wish they would leave me in peace. I want to be left alone.” Go to that situation, describe what happens and let it go through you.

Subject: A colleague turns ill. Now it will be even busier.

Therapist: How did that happen?

Subject: I have driven her on too much, I burdened her too heavily.

Therapist: Go to a situation which shows the consequences.

Subject: I can shut off from my colleagues and draw back into myself without talking about it.

Therapist: And what is the result of that?

Subject: Loneliness. (New emotional charge)

Therapist: What is the result of loneliness?

Subject: I feel cold and chilly. (New somatic charge)

Therapist: Where do you feel this chilliness strongest in yourself? At your heart, too?

Subject: Yes.

Therapist: Go to the moment of dying. How do you die? What do you experience?

Subject: Loneliness—and a feeling of spite. (New charge)

Therapist: Spite against who or what?

Subject: Against all these people.

Therapist: Your colleagues or your patients?

Subject: Both.

Therapist: Then you go to a place of overview. When you arrive there say Yes.

Subject: Yes.

Therapist: Then you go to a moment in that life where you could have taken a decision to prevent all this. When you arrive there, see what happened and what decision you could have taken. Let it go right through you and understand why you haven’t taken that decision. (Looks again for the moment of choice)

Subject: I tried to explain something to the person I worked with. I am instructing, but not well.

Therapist: Why not?

Subject: I couldn’t transfer it properly. I let things drift. I could have known things would get out of hand, but I consciously didn’t do anything about it.

Therapist: Why not? What stopped you?

Subject: I am afraid of responsibility. Afraid I can’t handle it. (New charge)

Therapist: That fear has come from somewhere. We won’t go into that now (time problem), but you get an impression where it came from, so you can go into it later when you want. You now get an impression of the source of the fear that you won’t be able to handle it. What comes up in you?

Subject: That disaster in Atlantis. (Smiles broadly and relaxes. Had a regression about this before. Now he understands the connection: a small catharsis)

Therapist: Is there an image with it for yourself?

Subject: Yes.

Therapist: You hold this image tight, like the first page of a book you can open. A fear arose. Through that fear you are frustrated and you cannot transfer well, and that is why you cannot handle the influx. You actually wanted to be on your own always, because you are afraid to delegate. The result is: I want to be left in peace. Did you find that peace?

Subject: No, but I do know that peace now. That fear is not as big as it was. There isn’t much left.

Therapist: “I want to be left in peace.” Do you still feel that? (Checks other charge)

Subject: I do not feel it now.

Therapist: What do you feel now?

Subject: Peace. (This is always an ambivalent word; it means only a partial catharsis. A real catharsis gives joy!)

Therapist: Then you come back now in your own way, in your own time.

Evaluation

Since this was a demonstration with limited time, I hardly explored the emotions. Still there was some catharsis—an insight. The patient started laughing over “that disaster.” Then he got something off his chest: He understood that fear from that Atlantean experience blocked him from delegating duties to his assistants. The link between “I want to be left in peace” and “I stand alone” was clear, too. In fact, this person had always stood alone, for that was his attitude. He might have helped that stream of people, but he could not handle it all. It was not real impotence. It was mechanically plodding on.

Those people did not look at themselves, and he didn’t look at himself; either. What he could not confer on others was the capacity to give to other people. He could only do it himself. And that comes with a cold heart. It drains you. But in fact, he was asking for it. He became ever more dignified and tired.

At the flick of a switch, a hangover life is created. A gray veil comes over it. And the cause here was a character postulate. He was not a victim of circumstances, but of his own program. The result was weariness.